Mikołaj Sokolski

Mikołaj Tomaszyk

Full Article: View PDF

How to cite

Sokolski M., Tomaszyk M., Concept of Caring Cities in the Light of Assumptions of Caring Ethics – Introductory Remarks, “Polish Journal of Political Science”, 2024, Vol. 10, Issue 4, pp. 18–32, DOI: 10.58183/pjps.02042024.

ABSTRACT

One of the problems of the modern world is the dynamization and atomization of society, a consequence of globalization and the COVID-19 pandemic era. This phenomenon is also evident in cities. The authors address these problems within the ethics of care framework. A concept derived from the psycho-philosophical reflection of feminism. From the perspective of care, they analyze those problems and challenges that theorists and practitioners of public policy-making are facing. Starting from thinking-centered assumptions, they point to a possible solution to prevent such problems – the concept of caring cities.

Keywords: ethics of care, care cities, city, city studies

Introduction

The second decade of the twenty-first century is characterized by the blossoming of many concepts and theories of regional development. The directions of these narratives are within the scope of the analysis of the impact of globalization on states and their tasks. Part of this discussion are issues regarding the role and importance of the state in relation to the units of local government. It should be noted that one of the many consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic is the valorization of the state administration apparatus in the management of the pandemic crisis, which for supporters of limiting local government power is an important argument in favor of centralization. On the opposite poles of the discourse, we will find on one side supporters of the model of a strong state, with instruments of state interventionism in times of difficult global and regional challenges; on the other side of the discourse, you can hear the arguments of specialists in favor of limiting state power in favor of territorial self-government. They argue that in difficult, emergency situations, local authorities, especially municipalities, can react more efficiently, being closer to the people and their affairs. The efficiency of action in this case is conditioned by clear legal bases and adequate financial resources.

Scientific reflection on the directions of development of modern cities is conducted by representatives of many disciplines of knowledge. It is observed in a global perspective that the direction of population migration leads from rural areas to cities and their functional areas. The challenge of local policy is to manage ever-larger cities with a diverse and dynamically changing demographic structure. If the ambition of many local politicians is to provide their inhabitants with decent living conditions, then the concern is that urban development will be conducted in a spirit of sustainable development, while ensuring an adequate level of resilience to threats arising from, among others, the perceived effects of climate change. The addressees of these policies are the residents. The dynamic social changes observed in recent times encourage a more precise understanding of their needs. This is not an easy task because as a result of many factors, these needs are changing more dynamically than ever before.

The subject of this article is a scientific reflection on the ethics of care and its assumptions, read in the light of selected concepts of caring cities. The authors proceed from the assumption that the starting point of reflection on urban policy is a set of thoughts, beliefs collectively perceived as the philosophy of the city. It is contemporary philosophical urban thought that we should look to for answers to questions about the spirit in which cities should develop, what needs their inhabitants have, what social attitudes are shaped in relation to what we call urbanity and urban lifestyle. The following research questions are considered:

- What constitutes the main axis of reflection on the ethics of care?

- How can the assumptions of the ethics of care support philosophical reflection on contemporary cities and the directions of their development?

- Can the assumptions of care ethics provide the basis for conducting “caring urban policy” and what should be understood under this term?

- What examples of the “caring cities” concepts are provided by the selected authors classified as urban modernists?

When we were working on this article, we adopted yet another assumption. Namely, the new trends in reflection on cities are characterized by an approach that combines the scientific achievements of several disciplines of knowledge. They are characterized by interdisciplinarity as well as application of many research methods and techniques by scientists. We realize that the living conditions of modern city dwellers are so diverse and dynamically changing that within one field of knowledge, we are unable to answer many questions posed by city managers and the addressees of their actions, i.e., residents.

Selected Assumptions of Political Ethics of Concern

Dorota Sepczyńska points out that the political theory of care is one of the latest trends in political philosophy, which plays an important role in shaping the debate on the construction of the theoretical foundations for a just society or, in the case of the present paper, a caring one.[1] Depending on the adopted research perspective, the axiological content of the considerations on the ethics of care can be perceived in different ways. In chronological terms, the foundations are consistent. The development of the indicated cognitive category is associated with the development of feminist thought and the scope of the issues addressed within the framework of the so-called caring society. The second wave of feminism was marked by the mutual influence and implementation of concepts such as Sarah Ruddick’s “Maternal Thinking,” Carol Gilligan’s psychological research on feminist moral development, and Nel Noddings’ philosophical foundations of care ethics.[2]

The ethics of care, within the framework of political interpretation, deals with the psychological and ethical assumptions of the perspective of female morality and its impact on the perception of socio-political reality and the construction of theories within it. The ethic of care, as a developing trend in philosophy and social sciences, finds its application in both theory and political practice. The contemporary challenges we face, such as regional and global migration, globalization resulting in deepening development differences, inflation of personal, social and political claims, technological progress and the digitization of social life, the clash of many alternative ethical concepts, secularization of public life, and moral relativization place concern at the central reflection on how to build sustainable, inclusive societies.

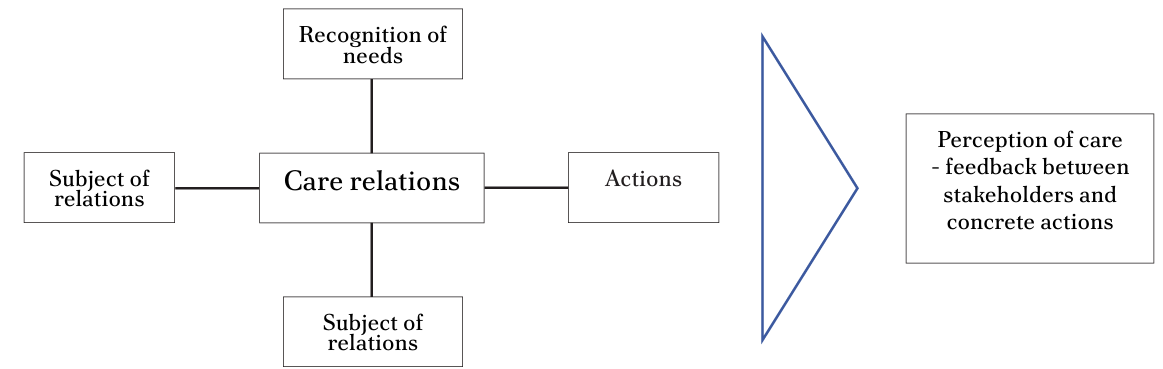

Against the backdrop of the changes we have signaled, feminist thinkers have introduced the concept of ethics of concern into the discourse. They apply this concept to considerations of a socio-political nature. Addressing the issue, they present the scope of three basic theoretical dimensions that enable the characterization of feminist thought in perspective, representation, difference, and point of view, which determine how a feminist decodes socio-political reality. Each category is subject to appropriate interpretation based on the guiding paradigms; they vary depending on the type of feminism adopted. Diagram 1 illustrates this.[3]

Diagram 1. Feminist theory of care[4] Source: own study.

Source: own study.

The ethics of care is related to the development of feminist thought. The subject of interest of feminist thinkers was not only limited to addressing issues of an axiological nature but also made it possible to build further categories and socio-political structures. Despite the indicated scope, the ethics of care as a term and its assumptions of a normative nature have determined the perception of feminism in terms of political science. Until now, as Andrzej Waleszczyński points out, there have been few studies and articles exploring the mentioned issue. Thus, it is important from our point of view not only to present the basic discourse shaping the ethics of care in feminist reflections, but also to extrapolate it as a cognitive tool enabling it to be seen in the activities of political entities active at the local government level.[5]

In the attempt to summarize the assumptions of the ethics of care on the attitude of the interpretive framework adopted by us, it should be noted that the basic dimension of care requires embedding in the social reality, in which the entities taking actions for the community function, which is to be a direct reference to the portrayed, the relationship between the caring subject and the object of care (mother-child relationship). However, this is not the only element that can be interpreted on the basis of the work of the selected thinkers (psychologists and philosophers): Carol Gilligan, Nel Noddings, Joan Tronto, and Judith Phillips.[6]

Thus, applying the interpretative and moral framework of the ethics of concern, it is necessary to look at the socio-political reality through the prism of contexts that are the consequences of human activity, and the need to change normative paradigms that define the moral horizon of the entire community in the era of exhaustion of universalist formulas, which were the result of masculine thinking and moral development. The indicated researchers and other representatives of the current of the ethics of concern postulate:

- Transformation of moral theory: Within the framework of this approach, the researchers of the issue, most notably Andrzej Waleszczyński, emphasize the importance of Virginia Held’s works in the presentation of how feminist perspectives have changed traditional moral theories. In this way, the attention is drawn to the performative influence of feminist thought on the shaping of the ways of interpreting socio-political reality, while at the same time referring to its inspirational character for bringing about social change. Held advocates for a moral framework that prioritizes care and relational ethics, contrasting with more conventional, justice-oriented approaches, thus abandoning the current contexts that determine moral development in the universalist sense, which in feminist thought is called masculine;[7]

- Paying attention to women’s experiences. An important inspiration for Held is thus women’s experiences in formulating ethical claims, the nature of which is fundamentally determined by the earlier exclusion of feminism’s perspectives on the shape and manner of social relations. Held, as well as previously indicated by Phillips and Noddings, questions the universalist way of formulating moral judgments and principles in the context of so-called big ideas such as justice.[8] They propose solutions that are case studies, i.e., situations and experiences that determine the ethical dimension of relationships, treating them as the basis for ethical reasoning and the formulation of moral principles;[9]

- The requirement to enter a cultural context of caring: An important challenge faced by the ethics of caring, as well as the basic context that generates an additional platform for reflection, is the cultural grounding of caring. It is not clear what concern it is in theoretical terms, as well as in social practice, and above all in the context of security. According to the assumptions presented by Stanisław Filipowicz and Maciej Kassner, the basic context of considerations of a political (or non-political) nature is culture.[10] Cultural grounding allows us to capture the appropriate research perspective not only for the concept, but also its derivatives, i.e., care or caring. It should therefore be stated that the cultural context is the primary basis for the implementation of concern in the process of conceptualization and operationalization of security, both in community and individual terms, which is the main area of interest of this work;

- The relational nature of existence: As part of the ongoing reflection on what the ethics of care is in an axiological sense, there is an ontological element. In addition to turning to the cultural context that defines the way care is understood, the relational nature of care must be pointed out. Caring is not only a value, but a practice that shapes ethical duties. Thus, compared to universalist ways of building moral judgments, the ethics of care advocates for a deeper understanding of care as both a dynamic relationship and a moral ideal. From the perspective of security, the ethics of caring also refers to understanding the needs of an individual as well as the entire community network, in the context of threats of the contemporary world such as marginalization, social conflicts, and economic crises.[11]

The Starting Points for Building a Caring Society

In addition to considering socio-political processes, as well as building normative foundations for social interaction, care can be presented as a moral determinant of new processes for political change. Phillips states: “Despite policy being a central area of care the opposite has not been the case: care not been central to policy. Daly and Lewis (2000) argue that care can be a category which improves the depth and quality of welfare stater analysis. Three dimensions of care – care as labor, care within a framework of obligations and responsibility, and care as an activity with cost – bring together care as activities and relations with the political, economic and social context to provide basis for cross-national comparison of the changing welfare regimes. The concept of care can be used analytically at both macro level (through the role of cash and services and the political activity of provision by and among the different sectors) and the micro level (…).”[12] The ethical issues underlying the concept of the state and the individual set the tone for the contemporary reconstruction of the state and a changing narrative about man and his relationship with his environment. The above is illustrated in Diagram 2.[13]

Diagram 2. Relationship of care

Source: own study.

Strengthening social capital, personalization of public policies and relational responsibility are the foundation of a caring society. Caring promotes both our life in society and the non-abuse of community resources. Without these, both the community and the building of a caring society are fundamentally at risk.

Caring, as a fundamental ethical and social category, redefines the way we think about the relationship of the individual to the community and of the community to institutions. Building a caring society assumes that each member of the community has the right to shape the social relationships and policies within it, but also a sense of security, support and equal opportunities for development. From a theoretical perspective, the ethics of care, as mentioned earlier, challenges traditional, hierarchical socio-political models, proposing relationships based on reciprocity and cooperation.[14]

Selected Concepts of Caring Cities

The analysis of the assumptions of caring ethics from the point of view of urban policy encourages a review of selected concepts of research on the city and its direction of development. In the literature of the subject, various concepts related to this area of research can be found. They focus on the analysis of the impact of global challenges on the life of a human being and their immediate environment. They also define how, in order to remain resilient to the negative effects of a turbulent urban environment, one can prepare for, respond to and prevent them. The characteristic features of the concepts of caring ethics are:

- seeing the impact of climate change on city life;

- seeing the relationship between human lifestyle and the pace of climate change;

- promoting participatory forms of power in the city;

- noticing the relationship between architecture and urbanism and the quality of life in the city;

- moving away from purely capitalistic pro-development motivations to promote the integral development of the individual;

- paying attention to the psychosocial determinants of city life;

- investigating the relationship between technology and the environment;

- changing the nature of the relationship and style of communication between residents and local political elites;

- consideration of gender differences affecting the way cities are planned and managed;

- recognition of social needs and a selection of legal financial instruments appropriate to circumstances and opportunities;

- increasing emphasis on improving the quality of life in the city in an integral way by identifying various aspects of human well-being and other factors.

In reference to the above selected characteristics that characterize this trend of urban research and development, the starting point in the context of care is the experience of the caregiver-caregiver relationship. Referring to the contents of the first and second chapters, we assume that, in stereotypical terms, it is the caregiver who is placed in a hierarchical relationship with the caregiver, who knows better what is possible and needed by the patient. It decides for the patient, while limiting his decision-making autonomy by appealing to the care derived from knowledge. This relationship can be referred to as the relationships between the holders of power and the citizens of cities.

However, the motivation for action that stems from the ethics of care reformulates these relationships in favor of a non-hierarchical approach, in which the caregiver makes the diagnosis, takes care actions not so much on the basis of a set of own attitudes and beliefs, but rather on the basis of the patient’s possible expectations. The person in power discerns the needs, examines the expectations, surveys the will of the residents, consults them for strategic decisions. It does not question, there are no ready-made clear solutions, but it diagnoses, moves away from stereotypes in favor of an individualistic approach. It adapts possibilities to local individual circumstances and needs.

In this sense, the ethics of care is dialogic – it prefers participatory forms of discernment of problems and needs of individuals and society, in order to develop possible legal, financial, organizational and non-schematic solutions based on them. The deliberative background of the activities motivated by the ethics of care involves changing the perception of the political leader, the official by himself, and thus his role in local politics, in the local community. Change lies in the willingness to give up attachment to one’s own visions and concepts in favor of discerning needs and considering other opinions. It is the willingness to pose the question: How can I help?

Criticism of a caring approach to the functioning of the city may accuse the inadequacy of the choice of management tools in challenging times, when other priorities are supported by a set of other values. It seems that we are once again at the stage of the neorealist narrative in global and regional politics. The attributes of power, which focus on protecting interests and spheres of influence, become important. They link power and the struggle for it to the anarchic nature of social reality and the combative nature of man. In this view, concern can be read as justification for violence as well as for violation of rights and freedoms of other people.

The ethics of concern in the way we see this reality is different. It seeks to understand and recognize the needs of urban dwellers. It argues that the selection of forces and resources necessary to implement public policies in the city will be better, more effective, if preceded by discernment, recognition of interdependence and differences. Moreover, it recognizes this point in an era of deepening social diversity and dynamic urban development, a spillover of urban sprawl. In such circumstances, it is necessary to change the tools of city management, reformulate the style of policy and adapt its priorities to the needs of individuals. The ethics of care is not the same set of new, revolutionary slogans, but it reformulates them. It changes the role and meaning in the urban political system, residents, activists of urban movements, politicians and local governments. It emphasizes that diversity is not a threat, but a creative tension unleashing new fields of activity of residents, it recognizes the differences in political preferences, in the positions of activists, and, without questioning their rightness, meets them.

One of the books that addresses the tenets of the ethics of care is a concept developed by David Sim. The author of “The Soft City” describes his concept in the belief that cities are not the problem, but rather the solution to contemporary problems. Referring to the diagnosis of the condition of the social fabric, he sees that “the fundamental difference between living standards and quality of life is that the standard of living depends on how much money we have and how we spend it, whereas the quality of life depends on how much time we have and how much we spend it.”[15]

Sims outlines the concept of a city whose politics is shaped by caring and inter-human relationships, between man and nature, between man as a consumer of goods and technology that can improve his life. It is an image that visualizes the other person in a positive light. Sim’s concept supports social diversity, efficient communication systems that promote zero-emission means of transportation, including pedestrian traffic. Sim’s soft city is a city of human scale that facilitates social interactions and thereby reduces the human distance created by the spatial and functional segregation of different parts of the city, even within a single quarter. Sim admits that “Therefore, the zoned city not only makes for an inconvenient everyday life, it also makes for a social challenge as different groups of people (ethnic, economic, trade/professional, age) don’t meet in a natural way as the idea of neighborhood disappears.”[16]

The concept of the soft city is a construct that supports friendliness through mutual knowledge, relationships, counterpoint and complement of the smart city and a turn toward already proven, not always expensive, human-centered solutions. It is characterized by gentleness, softened and thus perhaps better suited to current social needs, urban policy tools.

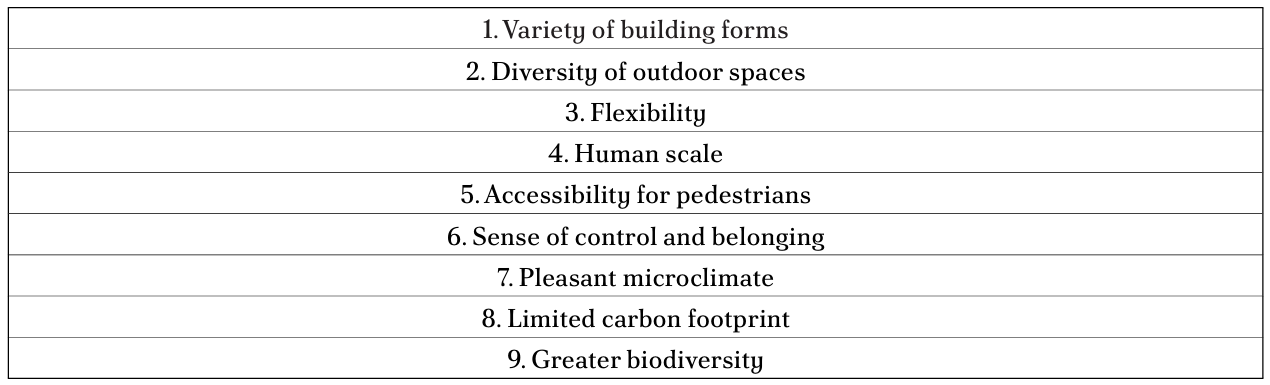

A soft or friendly city seeks simple solutions that mitigate the impact of climate change and neutralize extreme weather conditions so that residents can comfortably spend their time outdoors, it says that, “The town or city is a system of relationships, a place where multiple, overlapping systems of different relationships are co-located—public and private, common and individual, formal and informal” Sim writes.[17] It is the concept of how urban political elites function, administrations that are not just a brick-and-mortar political shell, but a complex combination of hardware and software. The common denominator of all these elements is the combination of density and diversity of everyday life, which enables people to function better together, he added. The nine principles of a friendly city are set out in table 1 below.[18]

Table 1. City rules

Source: own study.

The concept of Sim’s soft city refers to the ethics of care in at least two aspects. The first is the concern for nature, on the basis of which the author develops the idea of the eco-city. The second aspect is the concern for human-supporting spatial development. In reference to the first thought, the eco-city in accordance with the principles of care supports:

- revitalizing yards with the aim of preserving their microclimate;

- biodiversity;

- planting trees along the streets;

- establishing microgreens, winter gardens, etc. Green roofs that better conserve scarce water resources;

- social life located along rivers;

- a solution that eliminates the division of urban zones into public and private in favor of shared space;

- the use of natural energy and light sources, e.g., through the development of renewable energy sources;

- the possibility of frequent human contact with nature;

- small-scale solutions rather than large-scale solutions.

The concept emphasizes simplicity, convenience, naturalness, mutual friendliness, and accessibility of urban infrastructure combined with compact buildings adapted to diverse use.

The concept of the city was developed as part of a publication by Jonathan F. Rose called “The Well-Tempered City.” In his book, the author reflects on what role modern science, ancient civilizations, and human nature can play in charting the directions of development of modern cities. Rose proposes the principles by which city managers should be guided when thinking about their future. These are: coherence, resilience, community, compassion.[19]

As an important point of departure for the study of contemporary cities, the author recognizes that modern cities show much greater pressure towards the interdependence of their individual elements and entities of urban life than in the previous decades. This is the first point of contact with the ethics of care.

Comparing cities to adaptive systems shows a tendency towards homeostasis and symbiosis with the system’s environment, and drawing an analogy between the urban organism and the organisms of natural systems is innovative and creative. Central to this concept is the assumption that cities can be designed and managed in a way that responds to the needs of their inhabitants, while respecting natural resources and the environment. These systems consist of many moving parts, which are characterized by linear development and predictability, a peculiarly understood cyclicality. This dynamic view of the city corresponds with the approach that the main subject of urban policy is an active human being, developing in a dynamic environment. According to Rose, city is one of the most complex system created by man.[20] But it is manageable.

The concept of the common good, and of the urban culture that relates to it with care, is another element that supports and develops the ethics of care in the study of the city. In this concept, mutual trust, social capital that diminishes growing inequalities and divisions, and fear of the future of modern cities is an important aspect of building up resilience to events. Rose compares contemporary urban challenges to what in the U.S. military is called VUCA – volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. He goes on to say that the best way to address these megatrends is to think outside the box to build urban systems that are more integrated, resilient, and flexible, ready to prevent emergencies and predictable events based on an analysis of the impact of climate change on humans and their environment. According to Rose, consistency is a fundamental condition for urban prosperity. It is expressed, among other things, in the development of new urbanism that includes and overcomes existing divisions in the destiny of urban areas. Coherence is also postulated in the research on the metabolism of cities.[21]

Rose sees that the city, like any living organism, has its own metabolism. Energy, information, and matter flow through them. “As the world’s population grows and consumes more, a well-tempered city must excel in the second temperament, providing efficient, resilient, integrated metabolic systems that function in a circular manner that mirrors nature’s own process, through which one system’s waste is another system’s nourishment”[22] the author claims. Today, they are linear. They must take a circular form, consistent with the course of things in nature. Coherence, circularity, community, resilience, and concern are key elements of this concept. They provide a healthy balance between the interest of an individual and the well-being of the collective. Care and compassion, as Rose argues, “A key condition for restoration is compassion, which provides the connective tissue between the me and the we, and leads us to care for something larger than ourselves. Caring for others is the gateway to wholeness for ourselves and for the society of which we are part.”[23]

Summary

Introducing the concepts of “compassion” and “caring” into the narrative about contemporary cities presupposes the pursuit of development goals based on altruism. “[Cities] (…) need a pervasive culture of compassion, grounded in neighborhoods, nurtured in houses of worship, places of reflection and retreat, enhanced by the collective efficacy of for-profit and not-for-profit social entrepreneurs (…)”[24]; “(…) It can only grow in the soil of trust”[25] Rose writes. Concepts of caring cities are built on the foundation of interdependent social, economic, and political systems. The introduction of a moral principle to this narrative – altruism – gives them the necessary synchronicity, strengthening resistance to destabilizing risks that threaten the inhabitants of cities.[26]

The analysis of the two concepts of caring cities allows us to see that one of the most important challenges for urban communities is their dynamically increasing diversity of inhabitants. Hence the need to include in the narrative of the city a unifying and interweaving language, which supports the composition and union of man with nature. “Caring cities” is a concept of sustainable, just, and resilient urbanism that puts people and their relationships with their surroundings at the center. It is an essential set of beliefs consistent with the assumptions of caring ethics and the economics of feminism.

References

[1] D. Sepczyńska, Etyka troski jako filozofia polityki, “Etyka”, 2012, 45, p. 37, DOI: 10.14394/etyka.464.

[2] N. Noddings, Care Ethics and Virtue Ethics, in: The Routledge Companion to Virtue Ethics, eds. L. Besser-Jones, M. Slote, Routledge 2015, pp. 401–414; C. Gilligan, In a different voice: psychological theory and women’s development, Harvard University Press 1982; S. Ruddick, Maternal thinking, “Feminist Studies”, 1980, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 342–367; C. Gilligan, In a Different Voice: Women’s Conceptions of Self and of Morality, “Harvard Educational Review”, 1977, Vol. 47, Issue 4, pp. 481–517, DOI: 10.17763/haer.47.4.g6167429416hg5l0.

[3] R. Tong, T.F. Botts, Feminist Thought: A More Comprehensive Introduction, Westview Press 2017, p. 7; M.C. Nussbaum, On hearing women’s voices: A reply to Susan Okin, “Philosophy & Public Affairs”, 2004, Vol. 32, Issue 2, pp. 193–195, DOI: 10.1111/j.1088-4963.2004.00011.x; S. Ruddick, Maternal thinking, op. cit., p. 342.

[4] Determinants shaping the construction of feminist ethical systems.

[5] A. Bilski, Etyka Troski. Próba faktycznej troski?, “Perspectiva. Legnickie Studia Teologiczno-historyczne”, 2024, No. 1 (44), pp. 22–23; M. Sokolski, M. Tomaszyk, Doświadczenia organu prowadzącego przedszkoli i szkół Gminy Świebodzin w latach 2018-2024 z punktu widzenia założeń etyki troski, “Samorząd Terytorialny”, 2024, No. 10, pp. 58–71; A. Waleszczyński, Feministyczna etyka troski. Założenia i aspiracje, Środkowoeuropejski Instytut Zmiany Społecznej 2013, pp. 12–17.

[6] J. Phillips, Care, Polity 2007; N. Noddings, Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education, University of California Press 2003; J. Tronto, Moral Boundaries. A political argument for an ethic of care, Routlege 1993; C. Gilligan, J. Attanucci, Two Moral Orientations: Gender Differences and Similarities, “Merrill-Palmer Quarterly”, 1988, Vol. 34, No. 3, 223–237.

[7] A. Waleszczyński, Feministyczna etyka troski…, op. cit., p. 192; V. Held, Feminist Morality: Transforming Culture, Society and Politics, Chicago University Press 1993, pp. 33, 59.

[8] N. Noddings, Care Ethics and…, op. cit., pp. 401–414; J. Phillips, Care, op. cit.

[9] A. Waleszczyński, Feministyczna etyka troski…, op. cit., pp. 192–193.

[10] S. Filipowicz, M. Kassner, Nauki o polityce i zagadnienie interpretacji, Oficyna Wydawnicza Aspra-JR 2023.

[11] Ibidem, pp. 153–154.

[12] J. Phillips, Care, op. cit., p. 33.

[13] Ibidem.

[14] A. Waleszczyński, Feministyczna etyka troski…, op. cit., p. 46.

[15] D. Sim, Soft City. Building Destiny for Everyday Life, Island Press, 2019 (ebook).

[16] Ibidem, (ebook).

[17] Ibidem, (ebook).

[18] Ibidem, (ebook).

[19] J.F.P. Rose, The Well-Tempered City. What Modern Science, Ancient Civilizations, and Human Nature Teach Us About the Future of Urban Life, Harper Wave 2016.

[20] Ibidem, p. 173.

[21] Ibidem, p. 78.

[22] Ibidem, p. 76.

[23] Ibidem, p. 16.

[24] Ibidem, p. 179

[25] Ibidem.

[26] Ibidem, p. 181.