Kamal Chomani

Full Article: View PDF

How to cite

Chomani K., Corruption and Kurdish Nationalism: A Case Study of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, “Polish Journal of Political Science”, 2024, Vol. 10, Issue 2 (Special Issue), pp. 68–95, DOI: 10.58183/pjps.0302SI2024.

ABSTRACT

This paper critically examines the intersection of corruption and Kurdish nationalism in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). It focuses on the role of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) post-1991 as key representatives of Kurdish nationalism in the KRI, particularly the KDP. In contrast to the existing literature emphasizing the KRI as a symbol of Kurdish national identity, this study delves into the darker side of this narrative, highlighting how Kurdish nationalism has been manipulated to serve the interests of the ruling parties, particularly in the economic and political domains.

By qualitatively analyzing interviews and secondary sources in Kurdish and English, the paper explores the correlation between corruption and nationalism in the KRI, which have paralyzed the state-building processes, and the key promise of the Kurdish liberation movement to bring about democracy and social and economic justice.

Keywords: Kurdish nationalism, political corruption, state-building, informal institution

Introduction[1]

Academics on Kurdish studies have vastly focused on state-building,[2] the resistance of Kurds,[3] the plight of Kurds,[4] and more recently the success of the Kurdish story in Iraq.[5] There are fewer studies on the weaponization of Kurdish nationalism by the ruling two political entiti1s for the sake of maintaining their grip on power. While it is true, Kurdish nationalism has been studied and there are many studies contributing to the formulation of our understanding of Kurdayeti.[6] There are, however, significantly fewer studies that highlight the many ways Kurdayeti has been exploited by the ruling elite to maintain the status quo, i.e., the corrupt clientelist system in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

In the context of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, the intertwining of corruption and nationalism within the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) exemplifies how former revolutionary leadership tends to exploit nationalist sentiment in order to consolidate power and, effectively, capture the state. As indicated by Transparency International ranking Iraq (including the KRI) as highly corrupt,[7] the endemic corruption in the KRI – in the local and international media, in the KRG institutions, and among the leaders themselves – poses significant challenges to establishing transparent governance and rule of law. Although there are various reasons behind the failures of the KRI’s state-building, anti-corruption efforts, and good and democratic governance, how nationalist rhetoric is used to rationalize corruption is understudied, which will be the topic of this paper.

English-speaking Kurdish Studies scholars have often overlooked the intricate political dynamics within the KRI. This may stem from language barriers or a tendency to view Kurdish issues through the lense of international relations.

The economic, political, and cultural influence of the KDP and the PUK has significantly shaped Kurdish nationalism’s trajectory, known as Kurdayeti. Initially, Kurdayeti appealed to the Kurdish public’s intrinsic rights, including cultural recognition and self-governance. During the post-1991 Kurdish Uprising, and particularly in the years since 2003, marked by oil and gas exploration, a power struggle has ensued between these entities, shifting the focus from collective rights of the Kurdish liberation movement to resource control and power consolidation. These developments prompt a reevaluation of Kurdayeti’s impact on the socio-economic life post-1991 and reconsider whether revolutions or armed insurgencies foster liberty or merely establish new oligarchies and heightened militarism, a pertinent question for the KRI.[8]

The Uprising was a transformative period for the Kurds in Iraq, as it allowed them to translate their nationalist aspirations into tangible actions for the first time. The Uprising was not just a theoretical expression of their dreams, but a practical implementation of their long-held dreams. As Hama describes Kurdayeti, it is “the imagined Kurdishness for their political life, and its history has been an attempt to transform their dreams for liberation and freedom.”[9]

However, due to corruption and “betraying” the foundations of the imagined vision of Kurdish nationalism, Hama argues, “the practice of Kurdayeti also caused the fall of the utopia that the Kurdish nationalists had made in their expressions. […] The Kurdayeti, the imagined soul of Kurdishness, fell apart.”[10]

The case of Kurdish nationalism in the KRI illustrates the complexities of nationalist movements in the Middle East, where the outcomes frequently contradict the initial promises made to the public, underscoring the need for a critical reassessment of nationalism’s role in political and social transformation.[11]

By shedding light on these complex interactions, the paper aims to explore how Kurdish nationalism has been utilized by the KRI’s ruling elites to justify corruption in the KRI. It thereby contributes to a deeper understanding of the challenges faced by the KRI and the Kurdish nationalist movement. In doing so, it offers insights that are vital for policymakers, scholars, and stakeholders engaged in the region.

This paper is structured in the following manner: First, I will briefly introduce Kurdish nationalism and corruption; then, I will explore how corruption, more particularly political corruption, is justified through invoking nationalism; I will picture the landscape of corruption in the KRI, and focus on how nationalism was used to justify and rationalize the closure of the Kurdistan Parliament in 2015, the KRG’s oil policies, and the referendum for the independence of the KRI in 2017.

Literature Review

Kurdish Nationalism

Navigating the multifaceted concept of nationalism, particularly within the Kurdish context, reveals a landscape marked by diverse and sometimes contentious interpretations, yet unified by the underlying principle of self-determination within the liberation struggles for ethnic and cultural rights. This principle, outlined in the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1514 on decolonization, asserts the inherent right of peoples to define their political status and shape their development paths.[12] Kurdish nationalism varies significantly across regions, depending upon which country the particular Kurdish populace inhabits. In the case of the KRI, Kurdish nationalism has been a response to Arab nationalism characterized as “Arabism, Pan-Arabism, and nationalism on a local basis,”[13] and Kurdish nationalism often encapsulated by the term Kurdayeti.[14]

The genesis of modern Kurdish nationalism is closely linked to historical and geopolitical developments during the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, notably the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916.[15] This fragmented Kurdish territories between several states, thereby initiating a century-long saga of struggle, displacement, and resistance. Despite the protracted and so far unsuccessful struggle for a sovereign state, Kurdish nationalism remains a potent force, mobilizing substantial support for statehood and rights.[16] This complex historical trajectory encapsulates the complex interplay of regional geopolitics and international treaties (such as the Treaty of Sevres and Lausanne),[17] the relentless pursuit of Kurdish self-determination and statehood,[18] as well as the brief establishment of a Kurdish state in Mahabad in 1946 and its subsequent suppression.[19]

Moreover, the evolution of Kurdish nationalist movements, particularly the Kurdistan Workers’ Party’s (PKK) transition from armed struggle to a more inclusive social and cultural nation-building approach,[20] reflects broader shifts in Kurds’ strategies and objectives in pursuing their political rights. Nonetheless, the brief establishment of a Kurdish state in Mahabad in 1946 and its subsequent suppression[21] highlight the enduring challenges and aspirations of Kurdish struggle for autonomy and rights.

The overthrow of the Iraqi monarchy by General Abd-al-Karim Qasim in 1958 marked a pivotal moment in Iraqi history. The Agrarian Reform Law of 1958 aimed at redistributing land to peasants and diminishing the political influence of feudal lords was interpreted as a direct threat to the traditional power structures within Kurdish society, leading to discontent among Kurdish leaders like Barzani.[22]

Barzani’s return from Russia had initially positioned him as a supporter of Qasim, but his stance against the agrarian reforms and subsequent events highlighted his divergence from Kurdish aspirations towards freedom, focusing instead on preserving his tribal dominance. This early conflict over land reforms and tribal power dynamics foreshadowed the persistent intertwining of tribal interests with the Kurdish nationalist movement.[23] This is important to mention as this was the precursor to the KDP’s tribal structures that brought with it the corrupt feudal structures that persist even today.

The ideological split in Kurdish politics became evident with the division within the KDP in the mid-1960s, leading to a rift between Barzani’s tribal leadership and the more ideologically driven Political Bureau wing led by figures like Ibrahim Ahmed and Jalal Talabani. This division led to bloodshed between the PUK, which had been founded in 1975 in response to the collapse of the September Revolution (1961-1975), and the KDP at the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s.[24] The KDP’s Political Bureau wing criticized Barzani for his conservative and tribal approach at a time when leftist ideologies increasingly influenced Kurdis.[25] This ideological and intellectual division highlighted the challenges in unifying Kurdish resistance against the Iraqi regime.

Through these developments, the foundation for the modern KRI was laid, with the Barzani leadership establishing a governance model marked by clientelism[26] and corruption, deeply rooted in tribal loyalties rather than based on the promises the Kurdish insurgents had made for the public.[27] This period set the stage for the complex interplay of tribalism, nationalism, and governance challenges that would continue to characterize Kurdish politics in Iraq.

The Kurds are not a homogeneous nation as they hold diverse religious beliefs and social cultures. However, within the Kurdish nationalist liberation movement, these religious differences have largely been addressed. Therefore, Benedict Anderson’s definition of nationalism in his seminal work, Imagined Communities, is the definition I will use in this paper. Anderson describes “nation-ness, as well as nationalism, as cultural artefacts of a particular kind.”[28] He further defines a nation as “an imagined political community—and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign.”[29]

Corruption

The United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) refrains from providing a strict definition of corruption due to varying interpretations, though it is commonly understood as the misuse of public office for private gain.[30] Scholars like Andrei Shleifer and Robert W. Vishny offer a more specific definition, associating government corruption with the sale of government property for personal profit. They define government corruption as “[…] the sale by government officials of government property for personal gain.”[31]

The persistence of corruption, irrespective of a country’s democratic or autocratic nature, has prompted various national and international efforts aimed at prevention, education, and the enforcement of ethical standards to mitigate its detrimental effects on development and public resources.[32] The consequences of corruption extend beyond economic loss, eroding public trust, skewing public decisions, and favoring a privileged few, which in turn can lead to illegal capital flights and the deterioration of administrative and developmental goals.

Likewise, Gannet and Rector define corruption as follows: “Corruption is the dishonest or fraudulent use of power for personal gain, in which an actor puts personal or small-group interests ahead of the broader goals he or she has otherwise committed to serve.”[33] Corruption leads to formation of clientelist networks that hinder the establishment of new, more transparent institutions.[34] In post-colonial and post-conflict contexts, corruption may paradoxically play a role in economic efficiency and peace establishment, with informal actors wielding significant influence, sometimes complementing formal state functions.[35]

However, the notion that corruption can facilitate post-conflict transitions is contested, with arguments suggesting it hampers the transition from war to peace by undermining transparency and accountability, thereby enriching a select elite at the expense of broader societal needs and development.[36] Corruption’s intertwining with governance and conflict underscores its role in sustaining power for criminal factions, obstructing peace and development efforts, particularly in regions rich in natural resources, where it fosters clientelism and threatens democratic and state-building processes.[37]

Pelle Ahlerup and Gustav Hansson find out that “The level of nationalism, measured by the level of national pride among the population, has an inverted U-shaped relationship with government effectiveness.”[38] This could be interpreted in a different way in the case of the KRI, where nationalism used a rallying cry behind ideology to unite the Kurds to fight for their rights, and soon establish rule and order in the beginning of the 1990s when former Iraqi Baathist regime withdrew its administrative presence in the KRI provinces. However, post-2003 the KRI nationalism not only failed to unite the Kurds, but also became a mechanism for corruption practices.

Yasir Abdullah et al. find out that “Corruption becomes a norm in Kurdistan and all the government institution infected and the extent of corruption is very high in Kurdistan. The factors that caused corruption in Kurdistan are the political parties’ intervention in government institutions, lack of transparency, and nepotism.”[39] However, what is missing here is additional research on the mechanisms of rationalizing and justifying corruption, on which this paper mainly focuses. In this study, I mainly focus on political corruption, and for this I take from Inge Amundsen who defines political corruption as follows: “Political or grand corruption takes place at the high levels of the political system. It is when the politicians and state agents, who are entitled to make and enforce the laws in the name of the people, are themselves corrupt. Political corruption is when political decision-makers use the political power they are armed with to sustain their power, status, and wealth.”[40]

Amundsen further argues that political corruption should be considered “as one of the basic modes of operation of authoritarian regimes.”[41] The KRI, despite holding elections, has practiced a neo-patrimonial system. In neo-patrimonial systems, no clear line exists between public duties and private interests, leading to extensive corruption and privatization of public resources. In these systems, political corruption is deeply embedded and institutionalized, supporting the dominance and survival of the ruling elite.[42]

The rationalization of corrupt actions by public officials underscores a broader challenge in addressing corruption. Corruption sustains systems that undermine democratic principles and the rule of law, highlighted by the complex relationship between oil production, government revenue, and democratic pressures.[43]

Methodology

Interviews

This thesis is a case-study-based qualitative research study, with qualitative data mainly collected through elite interviews. In this paper, I conducted elite interviews with key political figures and individuals who hold or have held important positions of power and influence within their respective fields. The interviews provided significant insights and nuanced understanding of the political corruption and nationalism in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The methodology of this study is designed to unravel the intricate relationship between nationalism and corruption within the KRI. This approach emphasizes both qualitative insights through interviews and the examination of secondary sources.

To enrich the analysis, the study further incorporates interviews with a diverse range of stakeholders, including activists, politicians from across the political spectrum, policymakers, members of parliament, experts in various fields, and former politicians both from within and outside of the current political system. My intervewees were Goran Azad, former member of Kurdistan Parliament, Mala Bakhtiyar, former head of the PUK Political Bureau Administration, Rewas Fayaq, speaker of Kurdistan Parliament, Rebwar Kakayi, a lawyer and activist in Kirkuk, Yusuf Muhammad, former speaker of Kurdistan Parliament and member of Iraqi Parliament, Adnan Mufti, former speaker of Kurdistan Parliament, Dr. Niyaz Najmadin, assistant professor at Sulaymani University, Saro Qadir, KDP President Masoud Barzani’s senior adviser, Sarkawt Shamsuldin, former member of Iraqi Parliament, Qubad Talabani, Deputy KRG Prime Minister, and Ali Hussein, a member of the Kurdistan Democratic Party.

This selection criteria for interviewees are designed to capture a wide array of perspectives on the dynamics of nationalism and corruption in the KRI. I selected these figures from key political parties that reflect the political reality of the Kurdistan Region. The choice of interviews as a methodological tool is deliberate, allowing for tailored questions and follow-up inquiries that can adapt to the unique insights each respondent brings to the conversation.[44]

The study targets influential figures who have played significant roles in Kurdish nationalism, KRI’s political landscape, and the Kurdish experiment of self-governance. The interviews were conducted using various methods. Most were carried out via WhatsApp calls, with the exception of the interview with Mala Bakhtiyar, which was conducted on-site in As Sulaymaniyah, and the interview with Dr. Yusuf Muhammad, which was held via Zoom. These interviews, along with secondary sources in Kurdish and English, form the main data for this research. The scarcity of literature on the specific case of causality between corruption and nationalism underscores the unique value of these interviews.

As Grant McCracken notes, a long interview is a powerful qualitative method, revealing individuals’ mental worlds and daily experiences.[45] The primary and secondary sources thus far have provided historical event accounts, but as Yuval Harari points out, understanding changes within human stories is essential.

The interviews for this paper will be open-ended, allowing the participants from diverse political spectrums and fields to delve into their memories, ideas, and analyses in response to the questions raised during the interview. This comprehensive approach to the interview method is crucial as it enables a thorough exploration of the research topic, raising different questions in different contexts. The interviews are highly efficient as they can involve tailored queries and follow-ups, ensuring a thorough understanding of the subject matter.

Discourse Analysis

There is a very close relationship between language and social discourses. Language is not merely a means of communication for political regimes; it serves as a tool to create, promote, and hegemonize specific ideas, thus formulating a discourse. Discourse represents the materialization of language, conveying implicit or explicit meanings. The operationalization of language and words, whether verbal or non-verbal, constructs a discourse. As Stuart Hall states, “A discourse is a group of statements which provide a language for talking about, i.e., a way of representing a particular kind of knowledge about a topic.”[46] That is to say, discourse is described as a group and a combination of statements that make up a particular language framework to enable the representation and communication of specific knowledge and ideas regarding a political, social, and economic topic or topics.

In his seminal work Orientalism, Edward Said[47] discusses how representations and expressions of “others” can be problematic, as they are often manipulated to serve ulterior purposes rather than representing the subjects for their own sake. Said’s argument underscores the notion that discourse is deeply intertwined with political power; those in power can shape discourse to serve their interests. As Hall argue, “Those who produce the discourse also have the power to make it true – i.e., to enforce its validity, its scientific status.”[48] In the case of the Kurdistan Region referendum for independence, for instance, all the KRG institutions were utilized to convince people of the validity of the independence discourse.

Discourse not only reflects an innocent cultural exchange, but also perpetuates specific power dynamics that favor the powerful. Said reinforces this by stating that “It hardly needs to be demonstrated again that language itself is a highly organized and encoded system, which employs many devices to express, indicate, exchange messages and information, represent, and so forth.”[49]

As for the methodological step I took for the analysis and selection of the quotes and ideas for this paper, I first selected texts based on their relevance to the themes of nationalism, corruption, state-building, justifications, rationalizations, practices, the revolutionary legitimacy within the Kurdish nationalist movement and the practice of governance. Then came the criteria for analysis, which were based on their prominence in the public discourse and their representation of various prospects within the governance and nationalist movement. I also focused on the features of the discourse such as metaphors, narratives, framing, and terminological choices used by the interviewees. Such a systemic analysis of the features was aimed at uncovering the implicit and explicit meanings conveyed in the discourse and how they relate to the dynamics of power within the KRI.

Given that my primary and secondary sources involve words, communications, and both verbal and non-verbal expressions, discourse analysis is the most appropriate method for exploring the evolution of legitimation processes in the KRI. In my interviews, I will examine themes and concepts related to corruption, nationalism, rationalizations, justifications, practices, and the revolutionary legacy. Specifically, I will analyze how each side perceives corruption in relation to nationalism.

Findings and Analysis

Landscape of Corruption

This section meticulously examines the landscape of corruption within the KRI, linking its evolution to the early stages of Kurdish nationalism. It notes a significant increase after the 2003 US-led invasion, due to both the discovery of oil in the KRI and the flow of money through Baghdad and from the international community. These factors collectively diminished the political competition needed to promote democracy and good governance. Simultaneously, they amplified opportunities for self-enrichment, all the while maintaining the public’s focus on the more significant cause of nationalist aspirations and dreams as a justification for enduring hardships.

The inability to draft a KRI constitution in 2009, as permitted by Article 120 of the Iraqi Constitution, due to internal political disagreements and external pressures, notably from Turkey, has inadvertently supported the perpetuation of corruption within the KRI, for the KRG has not had clear constitutional regulations of how to define the political, financial, and economic aspects of public administration.[50] This failure has further enabled ruling parties to entrench their power because in the absence of a constitution clearly defining the governance principles certain institutions have defined the issues that have led to political corruption, exploiting the separation of powers—executive, legislative, and judiciary—for personal, partisan, and familial gains. This became much clearer in August 2015, when the KDP utilized the Consultative Council to extend former KRI president Masoud Barzani’s term to another two years illegally.[51]

During the 1991 Kurdish Uprising, the KDP, the PUK, and other minor factions reestablished their presence in urban areas. Mulazim Umar, a prominent PUK leader, spearheaded the Peshmerga’s efforts to reclaim the city of As Sulaymaniyah. Masoud Barzani led the Kurdistani Front, an interim governance body tasked with restoring order and governance in the aftermath of the Iraqi government’s withdrawal from the KRI. Despite their resistance against Saddam Hussein’s regime, the KDP and the PUK were implicated in the looting of regional assets. In a letter dated March 9, 1991, Mulazim Umar conveyed to Masoud Barzani: “Merely a day ago, facilities including the cigarette factory, petrol station, and the Directorate of Education, alongside the premises of Hasib Salih and Abu Sand Restaurant, in addition to several government buildings, were subjected to looting […].”[52]

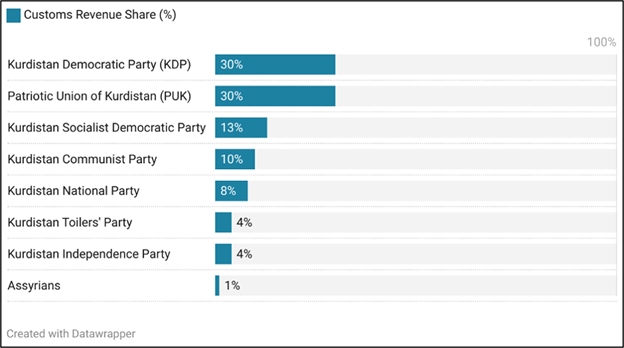

The Kurdistani Front aimed to manage daily civic life pending the establishment of a permanent government; however, the promises were not fulfilled. Nawshirwan Mustafa discusses the distribution of customs revenue, which was the primary source of income for the KRI after 1991.[53] See the chart below.

Chart 1. Customs Revenue Share (%) in 1992

Source: Own elaboration based on N. Mustafa, What are the KDP and PUK problems about?, 1995, https://www.kurdipedia.org/default.aspx?lng=1&q=2012083021583136678, (access 14.11.2024).

Mala Bakhtiyar expressed profound disdain for the Kurdistani Front. This entity, at the core of Kurdayeti governance during 1991 and 1992, has left a lasting impact on the region. He said: “Following the Uprising, the trajectory took a perilously detrimental turn. The Kurdistani Front pillaged Kurdistan. […] The Kurdistani Front not only looted Kurdistan, but also facilitated the smuggling of equipment, imposing taxes at border points with revenues distributed among Kurdish political factions. Such practices are unparalleled by any political entities or governments globally.”[54]

Corruption and clientelism operate in tandem, reinforcing each other. This relationship manifests through networks of patronage, where personal and political affiliations override meritocracy, undermining democratic principles and obstructing societal progress. The KDP and the PUK invented a system of governance colloquially known as “Penca be Penca,” which means everything was divided equally between the KDP and the PUK, from employing public employees to members of parliament. This is the foundation of the corrupt system that has continuity to the present day.[55]

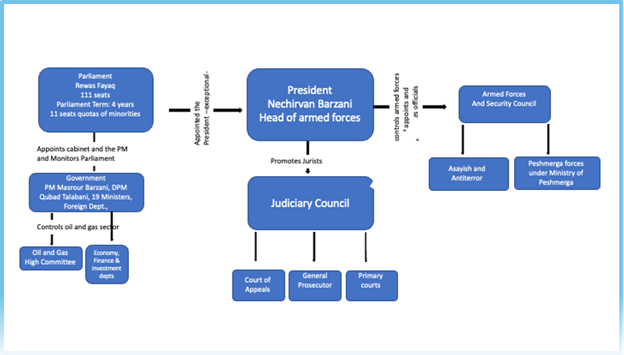

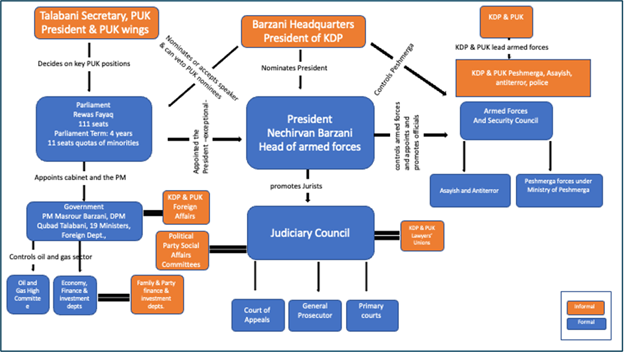

Informal political mechanisms, represented in Figures 1 and 2, reveal how formal institutions are manipulated by the ruling parties. The Kurdish political parties play the role of the government, the parliament, and the judiciary. According to Nawshirwan Mustafa, the political parties are higher than the KRG institutions.[56]

Figure 1. Formal Politics in the KRI[57]

Source: The figure was created based on records and laws of the KRI Parliament. All the laws are publicly available and can be accessed through the KRI Parliament’s website: https://www.parliament.krd.

Figure 2. Formal and Informal Politics in the KRI[58]

Source: Own elaboration and collection based on the KDP and the PUK bylaws, their media and the general Kurdish media.

For instance, the judiciary’s independence is compromised by party-affiliated social affairs departments, and the Peshmerga forces remain divided along party lines despite international calls for unification.[59] Such dynamics not only facilitate corruption, but also impede the establishment of a just and transparent governance structure.[60]

However, Saro Qadir, a key KDP intellectual and advisor to Masoud Barzani, believes that the KRG’s failures are not specific to the KRI’s revolutionaries; it is universal that revolutionaries have rarely succeeded.[61]

The 2020 International Transparency Organization report, as interpreted by Stop, a leading anti-corruption organization in the KRI, indicates that democratic nations characterized by robust freedom of expression, democracy, transparency, and solid institutional frameworks lead in combating corruption. Conversely, the regions where political corruption is not penalized find themselves lagging. Although the KRI isn’t specifically mentioned, it falls under the scrutiny of the International Transparency Organization’s recommendations aimed at enhancing democratic practices and institutional integrity, highlighting the need for greater freedom of expression, stringent measures against cross-border corruption, fortified oversight mechanisms, and increased governmental transparency.[62]

Sarkawt Shamsuldin, former Kurdish member of the Iraqi parliament, encountered significant opposition, including being branded a “traitor” by some KDP members and media, due to his critique of the KRG’s practices. He describes corruption in the KRI as predominantly “top-down,” originating from the upper echelons of power, where governmental and party positions are exploited for financial gain and securing advantageous contracts without fair competition, underlining a systemic absence of accountability.[63]

The challenge of quantifying corruption in the KRI is exacerbated by a dearth of transparency and accessible data. For instance, a 2021 investigative report by the American Prospect, which unveiled Prime Minister Masrour Barzani’s alleged $18 million property acquisition in the USA, was met with deflection from the Prime Minister’s office, further illustrating the difficulties in addressing corruption.[64] Prime Minister Barzani simply deviated from his corruption case of $18 million by calling the husband of an activist who had nothing to do with the report “treacherous” and that certain people plot against the KRI.

Rewas Fayaq, former Speaker of the Kurdistan Parliament (2019–2023), acknowledges the widespread nature of corruption and emphasizes the necessity for a multifaceted approach to combating this issue. Corruption has infiltrated every sector of life in Kurdistan, threatening to become “a cultural norm.” This pervasive issue highlights a significant gap between legislative frameworks and their practical enforcement, pointing to a broader problem of insufficient political will to uphold the rule of law.[65]

Deputy Prime Minister Qubad Talabani underscores the KRG’s commitment to address corruption, citing the 2020 law reform aimed at enhancing the accountability of the public. Talabani likens corruption to bacteria, thriving in environments characterized by chaos, unclear regulations, and bureaucratic inefficiencies, suggesting that closing loopholes and digitizing governmental processes could significantly mitigate corruption practices.[66]

The Kurdistan Parliament Scenario

Established post-1991 Uprising, the Kurdistan Parliament saw a division of seats and power between the KDP and the PUK from its very beginning, solidifying a system known colloquially as “fifty-fifty.” This arrangement has faced criticism for legitimizing two-party rule rather than facilitating genuine democratic governance. Goran Azad, former PUK MP, argues that the parliament serves more as “a facade for democracy,” often sidelining post-war elections to consolidate party power and entrench the clientelist system. This system rewards loyalty over meritocracy, ensuring that decision-making remains under the control of political party elites rather than being driven by parliamentary debate or public accountability.[67]

In the 1990s, the KDP and the PUK were using their revolutionary heritage to prop up their clientelist system. Former Kurdistan Speaker of Parliament Adnan Mufti (2005–2009), a member of the PUK, believed that the competition for popular support between the two parties led to increasing corruption in the system:“For instance, in Sulaymaniyah, if the PUK had employed 100 people, the KDP would employ 150 or 200 and distribute lands just to win the people over, doing more and more. As a result, a significant amount of corruption emerged after the fall of the regime.”[68]

The parliament’s vulnerability to closure by the KDP, as seen in 2015 during the Change Movement party’s efforts to amend the presidential law, underscores the challenges to legislative independence. It is an excellent example of how the parliament was used as a means of justification for the KDP-PUK duopoly, and it was closed whenever it was expected to become a threat to this duopoly.[69]

The closure highlights the institution’s lack of autonomy. The repeated suspension of parliamentary activities, as observed in 1994 and also more recently in 2015,[70] indicates a pattern that suggests the parliament’s role is perceived as instrumental rather than foundational to democratic governance.[71]

Instances where the parliament’s attempts to address presidential term limits or amend election laws were obstructed further illustrate the grip of the ruling parties over legislative processes. Such maneuvers, including the extension of Masoud Barzani’s presidency beyond constitutional limits under various pretexts, reveal a broader strategy of leveraging nationalist rhetoric for political expediency.[72] This approach prioritizes party interests over legal and democratic norms, with nationalism being invoked to justify actions that consolidate power and resist accountability.[73]

Kurdish Nationalism and Political Justification

The ruling parties’ use of nationalist appeals to legitimize undemocratic practices underscores a critical tension between the nationalist rhetoric and democratic principles.[74] This examination reveals a complex landscape where Kurdish nationalism, while a potent force for collective identity and aspiration, risks being co-opted by political elites to sustain its status quo marked by clientelism, lack of transparency, and limited public participation in governance. Dr. Muhammad continues to note that: “The KDP and Masoud Barzani had lost all political, popular, and parliamentary legitimacy; the only thing they used to justify closing the parliament for two years, was the nationalist legitimacy.”[75]

Although the Peshmerga forces should be under the command of the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs as per the KRI Parliament’s Peshmerga Law (Law number 5, year 1992) and the Political Parties Law (Law Number 17, Year 1993), the KDP and the PUK kept their Peshmerga forces as militias and never allowed their militias to be integrated with the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs.[76] Certain Kurdish politicians and oppositional political parties, as well as critics from the international community, have criticized the KRG for this;[77] however, the responses from the KDP and the PUK have been using nationalist sentiments mobilizing their Peshmerga forces to hold big protests against the opposition parties and leaders who called to end “corruption in the Peshmerga.”[78] Adnan Osman, former member of Parliament from the Change Movement (Gorran) faction, faced intimidation and death threats as the KDP and the PUK Peshmerga forces were mobilized for protests against him in 2010 when he called out the Peshmerga as militias. The entire KDP and PUK Peshmerga forces, as well as pensions, are being paid by the KRG, while these forces are forced to vote for their respective parties during the elections, hindering democracy and helping the two parties further consolidate power.[79] Osman said: “[…] Their principal tool was the use of nationalist rhetoric that positions the Peshmerga as a red line that must not be disrespected, invoking their own claims of national prestige.”[80] He concluded: “Nationalism undoubtedly acts as a means to both justifying corruption and to intimidate and suppress the critics and adversaries of this delicate governance model.”[81]

Former Speaker of Parliament Fayaq concluded with a stark statement on how nationalism has justified corruption in the KRI: “Consequently, under the guise of revolutionary principles and legitimacy, they have sanctioned numerous illicit activities and practices that have fueled the existing corruption.”[82]

The Referendum for the Independence of Kurdistan

This part explores the instrumental use of the 2017 independence referendum as a means to justify and perpetuate corruption within the KRI.

On September 25, 2017, a significant majority of Kurdish voters supported independence from Iraq in a referendum. This vote, led by then-President Masoud Barzani, whose term had controversially been extended past its legal limit, became a pivotal moment in how Kurdish nationalism can be utilized to gain one’s corrupt power. The decision to proceed with the referendum, despite international and regional opposition, was framed by Barzani as a step towards defining borders and achieving independence. Critics, including former Iraqi first lady and the key PUK decision-maker Hero Ibrahim Ahmad, viewed the referendum as an act of “stubbornness” with costly consequences for the Kurdish people as the KRI lost authority over the territories it had brought under its control during the war on ISIS, reflecting internal opposition and concerns over the timing and potential fallout of such a move.[83]

Goran Azad articulates that the referendum was employed as leverage to secure greater autonomy and control over oil-rich areas while also providing a pretext for extending Barzani’s presidency under the guise of necessity due to the ongoing conflict with ISIS. This duality highlights how nationalist aspirations were co-opted for political gain, reinforcing the ruling party’s power under the banner of independence.[84]

The referendum continues to be invoked by politicians to shield themselves from corruption allegations. For example, Rebwar Talabani, former head of Kirkuk Provincial Council, framed corruption charges against him as politically motivated attacks on his Kurdish nationalist stance.[85] This claim is contested by civil activists and legal experts, who argue that the allegations are based on concrete evidence of misuse of public funds, indicating a pattern where nationalist rhetoric is employed to deflect from accountability and corruption.[86]

The 2017 independence referendum in the KRI exemplifies the use of aggressive nationalist discourse. This nationalist rhetoric not only justified the suppression of dissent, but also played a critical role in maintaining the ruling class’ dominance by misappropriating public revenues and controlling public contracts.[87]

Former KRI President, as the main character behind the referendum, turned his enmity with former Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al Maliki to justify the imposition of his will on the people of the KRI to hold the referendum. In two separate interviews with Saudi international Asharq al Awsat newspaper in 2014 and 2017, Barzani reiterated that if former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al Maliki returns to the premiership, he would “announce the independence of Kurdistan.”[88] Likewise, in 2014, Barzani had also “threatened a referendum in Kurdistan if Maliki gets third term.”[89]

Oil and Natural Resources in Kurdistan

This part discusses the pivotal role of oil and natural resources in the economic and political dynamics of the KRI. It focuses on how these resources have influenced relationships within the region as well as with the Iraqi central government. Moreover, it notes how nationalist discourse has been utilized to formulate the KRG oil policies that serve the interests of the elite.

Alessandro Tinti’s empirical analysis of extractivism in the KRI further illustrates how resource management has fostered identity formation, reshaping of nationalism, and the establishment of a dynastic rule characterized by party allegiances and a crony patronage system.[90]

In brief, as Nils Wörmer and Lucas Lamberty wrote on President Barzani’s referendum motifs, Barzani aimed to pressure Baghdad and the international community for Kurdish independence before the KRI elections, divert focus from the KRI’s political and economic issues, and solidify Kurdish control over the disputed areas, notably Kirkuk for its oil.[91]

The pursuit of economic independence through oil revenue has been a significant focus for the KRG, with plans announced in 2013 to increase oil exports and achieve financial autonomy from Baghdad. These ambitions, articulated by former Minister for Natural Resources Ashti Hawrami, have faced challenges, contributing to economic crises and exacerbating tensions with Baghdad over revenue sharing and resource control.[92]

The social corporate responsibility scheme within oil contracts and the secrecy surrounding these agreements underscore the opaque nature of the sector. Speaker of Parliament Dr. Rewas Fayaq and Deputy Prime Minister Qubad Talabani offer different perspectives on transparency, with Talabani citing the engagement of international auditors as a step towards openness, despite ongoing secrecy concerns. On the other hand, Dr. Fayaq has shared concerns over the KRI’s lesser transparency especially in oil sector on several occasions.[93]

The ruling parties leverage fears of federal retribution to justify non-disclosure of financial details. This manipulation extends to portrayals of the Iraqi state as both a threat and an entity moving towards a developmental model, challenging narratives that justify secrecy and unilateral action by the KRG.[94]

KDP Political Bureau’s Arif Rushdi’s comments connect the defense of the KRI’s oil industry to notions of patriotism and dignity, illustrating how nationalist rhetoric is employed to rally support for the KRG’s positions against the Iraqi government.[95] In the KNN TV interview, when asked if he thinks the KRI people would defend the KRG’s oil industry when there is a threat from the Iraqi government on the KRG oil, Rushdi said: “Whoever is a nationalist, whoever has dignity, yes, should defend [the KRG’s oil industry]. But if someone is not a patriot, then they will not defend the KRI. It was also similar during the Saddam Hussein era. There were 300,000 Kurdish armed men [within the ranks of Iraqi armed forces]. But I believe the majority of the people of Kurdistan will defend the KRI. At the time of manhood, they are men.”[96]

Ali Hussein, the Political Bureau member of the KDP, connects the decision of the KRG’s independent exports and economic independence not with the KRG’s economic policy, but rather justified the decisions with the Iraqi government’s pressures on the KRG to submit to Baghdad’s will: “The Kurdistan Region’s budget was cut when it faced economic hardship. Since 2013, no financial opportunities have been allowed for Kurdistan as Iraq aimed to economically pressure Kurdistan to submit to Baghdad, contrary to the Iraqi constitution. In the Kurdistan Region, it was believed that Baghdad should be a democratic entity upholding human rights and constitutional principles, including Kurdish rights. If Baghdad adhered to these, Kurdistan might have considered delaying the oil extraction decisions.”[97]

Conclusion

Corruption persists in the KRI despite numerous efforts by both local and international entities to dismantle these socio-political and economic infrastructures. Historically, the Kurdish population, subjected to decades of conflict, sanctions, and discriminatory policies—including genocide—by the Iraqi government, refrained from scrutinizing the actions of insurgent groups. These groups, utilizing nationalist rhetoric and the pursuit of Kurdish rights, solidified their authority and established networks based on family, clan, and group affiliations to consolidate power and capture the state. The economic foundation for these networks established itself from the beginning of the post-Kurdish Uprising in 1991; however, it was significantly bolstered by oil exports which began in 2007.

The KDP and the PUK, having led the KRG since the early 1990s, have consistently employed nationalist discourse to rationalize corrupt practices. Their reliance on nationalism has not only enabled them to maintain power, but also coerced society into supporting them, even when faced with critical decisions such as the 2017 independence referendum.

The policy implication of this paper is that effective anti-corruption measures require a nuanced understanding of power dynamics, capable of altering the perceived benefits of corrupt behavior, as well as reshaping public standards of propriety and social legitimacy. However, as long as the political discourse in the KRI revolves around nationalism—a narrative fervently maintained by the regional elite to secure their dominance—meaningful progress remains elusive.

The findings of this study support the theory that views nationalism as a tool for political legitimacy for an ethnic group without a state to create a collective consciousness, which aligns with Anderson’s “imagined communities.” However, the very concept of nationalism can be exploited by the ruling parties, as in the case of the KRI, to use nationalist rhetoric to justify corrupt practices and consolidate power.

Lastly, the pervasive nature of corruption within the KRI, sustained by a complex web of clientelism, political patronage, and familial power dynamics, underscores the critical need for comprehensive reform and genuine political will to dismantle these entrenched systems. Without such efforts, the aspirations for a democratic, transparent, and equitable governance structure in the KRI remain elusive, hindering the region’s potential for sustainable development and societal progress.[98]

References

[1] I would like to extend my thanks to my friend Dr. Seevan Saed for his review of the paper, comments, and feedback. Lastly, a very special thanks to my friend Sushobhan Parida from the Universität Leipzig for kindly editing the paper and providing me with extensive comments and feedback.

[2] M. Ihsan, Nation Building in Kurdistan: Memory, Genocide and Human Rights, Routledge 2016; O. Bengio, Kurdish Awakening: Nation Building in a Fragmented Homeland, University of Texas Press 2014; M. van Bruinessen, Kurdish Ethno-Nationalism versus Nation-Building States, Isis Press 2000.

[3] M.R. Rostami, Kurdish Nationalism on Stage: Performance, Politics and Resistance in Iraq, Bloomsbury 2019; O. Alger, Kurdistan History, and Resistance: Turkey Kurd, Iraqi Kurd, Iran Kurd, Syria Kurd, Kurds in Asia and Eastern Europe, CreateSpace Independent Publishing 2016; A.K. Ozcan, Turkey’s Kurds: A Theoretical Analysis of the PKK and Abdullah Ocalan, Routledge 2012.

[4] I. Sadiq, Origins of the Kurdish Genocide: Nation-Building and Genocide as a Civilizing and De-Civilizing Process, Lexington Books 2021; M. Ihsan, Nation Building in…, op. cit.; M.M.A. Ahmed, Iraqi Kurds and Nation-Building, Palgrave Macmillan 2012, DOI: 10.1057/9781137034083.

[5] S. Fazil, B. Baser, Youth Identity, Politics and Change in Contemporary Kurdistan, Transnational Press 2021; D. Natali, The Kurds and the State: Evolving National Identity in Iraq, Turkey, and Iran, Syracuse University Press 2005.

[6] N. Christofis, The Kurds in Erdogan’s ‘new’ Turkey: Domestic and International Implications, Routledge 2021; S. Fazil, B. Baser, Youth Identity, Politics…, op. cit.; M. Cabi, The Formation of Modern Kurdish Society in Iran: Modernity, Modernization and Social Change 1921-1979, Bloomsbury Publishing 2021; M.S. Mustafa, Nationalism and Islamism in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq: The Emergence of the Kurdistan Islamic Union, Routledge 2021.

[7] Corruption Perceptions Index, Transparency International, https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020, (access 08.06.2022).

[8] E. Weede, E.N. Muller, Consequences of Revolutions, “Rationality and Society”, 1997, Vol. 9, Issue 3, pp. 327–350, DOI: 10.1177/104346397009003004.

[9] A.Q. Hama, Kurdayeti and literature; Discourse of Qubadi Jalizada’s poetry between opposition and balance discourse; a sociological view, Slemani: Culture Magazine 2019, https://cultureproject.org.uk/kurdish/kurd-adab-ako-qadr/?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTAAAR3Kz0eZdGhF9btqJTUI1cEmVxU-zECdAMYrv_7paxAaDU7GSULcatjUNao_aem_ASspWlls1Gy8pqP0pJkXhd6p4TfzpLXROEA58W-vA4NSvmahw66QyS0jytcnl-s95VlmJRzj9nxdR243lVM34Ms9, (access 15.01.2024).

[10] Ibidem.

[11] M.Y. Taha, Media and Politics in Kurdistan: How Politics and Media Are Locked in an Embrace. (Kurdish Societies, Politics, and International Relations), Lexington Books 2020.

[12] Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Cultural Survival 2007, https://www.culturalsurvival.org/undrip , (access 19.05.2024).

[13] P. Manduchi, Arab Nationalism(s): Rise and Decline of an Ideology, “Oriente Moderno”, 2017, Vol. 97, Issue 1, pp. 4–35.

[14] D. Natali, Kurdayetî in the Late Ottoman and Qajar Empires, “Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies”, 2002, Vol. 11, Issue 2, pp. 177–199, DOI: 10.1080/1066992022000007817.

[15] C.J. Edmonds, Kurdish Nationalism, “Journal of Contemporary History”, 1971, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 87–107.

[16] G. Stansfield, The unraveling of the post-First World War state system? The KRI and the transformation of the Middle East, “International Affairs”, 2013, Vol. 89, Issue 2, pp. 259–282, DOI: 10.1111/1468-2346.12017.

[17] O. Ali, The Kurds and the Lausanne Peace Negotiations, 1922-23, “Middle Eastern Studies”, 1997, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp. 521–534.

[18] D. Natali, The spoils of peace in Iraqi Kurdistan, “Third World Quarterly”, 2007, Vol. 28, Issue 6, pp. 1111–1129, DOI: 10.1080/01436590701507511; R. Olson, The Kurdish Question in the Aftermath of the Gulf War: Geopolitical and Geostrategic Changes in the Middle East, “Third World Quarterly”, 1992, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 475–499.

[19] A. Vali, The Forgotten Years of Kurdish Nationalism in Iran, Springer International Publishing 2020, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-16069-2.

[20] S. Saeed, Kurdish politics in Turkey: From the PKK to the KCK, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group 2017.

[21] A. Vali, The Forgotten Years…, op. cit.

[22] F. Baali, Agrarian Reform in Iraq: Some Socioeconomic Aspects, “The American Journal of Economics and Sociology”, 1969, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 61–76.

[23] S. Rashid, Dialogue of the Age: Memoirs of President Jalal Talabani, Slemani: Karo Press 2017.

[24] M.M.A. Ahmed, Iraqi Kurds and…, op. cit.

[25] M.M. Gunter, The KDP-PUK Conflict in Northern Iraq, “Middle East Journal”, 1996, Vol. 50, No. 2, pp. 224–241.

[26] A.H. Bali, The roots of clientelism in Iraqi Kurdistan and the efforts to fight it, “Open Political Science”, 2018, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 98–104, DOI: 10.1515/openps-2018-0006.

[27] M. Rubin, Kurdistan Rising?: Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region, American Enterprise Institute 2016; K. Hassan, Kurdistan’s Politicized Society Confronts a Sultanistic System, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 2015.

[28] B. Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Verso 2006, p. 4.

[29] Ibidem, p. 6.

[30] D. Mistree, G. Dibley, Fighting Corruption and Building the Rule of Law in the KRI, Stanford Law School 2018, https://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Mistree-Dibley-Corruption.4.18.18.pdf, (access 20.12.2023); L. Holmes, Corruption: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press 2015.

[31] A. Shleifer, R.W. Vishny, Corruption, “The Quarterly Journal of Economics”, 1993, Vol. 108, Issue 3, p. 599, DOI: 10.2307/2118402.

[32] D.J. Gould, J.A. Amaro-Reyes, The effects of corruption on administrative performance: Illustrations from developing countries, World Bank 1983.

[33] A. Gannett, C. Rector, The Rationalization of Political Corruption, “Public Integrity”, 2015, Vol. 17, Issue 2, p. 166, DOI: 10.1080/10999922.2015.1000654.

[34] R. Belloni, F. Strazzari, Corruption in post-conflict Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo: A deal among friends, “Third World Quarterly”, 2014, Vol. 35, Issue 5, pp. 855–871, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2014.921434.

[35] Ibidem.

[36] I. Spector, The benefits of anti-corruption programming: Implications for low to lower middle-income countries, “Crime, Law and Social Change”, 2016, Vol. 65, pp. 423–442, DOI: 10.1007/s10611-016-9606-x; Y.G. Zabyelina, ‘Buying Peace’ in Chechnya: Challenges of Post-Conflict Reconstruction in the Public Sector, “Journal of Peacebuilding & Development”, 2013, Vol. 8, Issue 3, pp. 37–49, DOI: 10.1080/15423166.2013.860343.

[37] J.J. Andersen, J.H. Hamang, M.L. Ross, Declining Oil Production Leads to More Democratic Governments, CGD Working Paper 620, Center for Global Development 2022, https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/declining-oil-production-leads-more-democratic-governments.pdf, (access 14.11.2024).

[38] P. Ahlerup, G. Hansson, Nationalism and government effectiveness, “Journal of Comparative Economics”, 2011, Vol. 39, Issue 3, p. 446.

[39] Y. Abdullah, (گەندەڵی کارگێری لە دامودەزگاکانی حکومەتی هەرێمی کوردستان و و کاریگەری و دەرهاویشتەکانی) Causes and Consequences of Administration Corruption in Kurdistan Regional Government, SSRN Scholarly Paper 2019, p. 5, DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.3404875.

[40] I. Amundsen, Political Corruption: An Introduction to the Issues, CMI Working Paper, CHR Michelsen Institute Development Studies and Human Rights 1999, p. 3.

[41] Ibidem, p. 4.

[42] I. Amundsen, Political Corruption…, op. cit., p. 9.

[43] J.J. Andersen, J.H. Hamang, M.L. Ross, Declining Oil Production…, op. cit.

[44] D. Brancati, Social Scientific Research, 1st ed., SAGE Publications 2018.

[45] G. McCracken, The Long Interview, SAGE Publications 1988, DOI: 10.4135/9781412986229.

[46] S. Hall, The West and the rest: Discourse and power, in: Modernity: An introduction to modern societies, eds. S. Hall, D. Held, D. Hubert, K. Thompson, Wiley-Blackwell 1996, p. 201.

[47] E.W. Said, Orientalism: Western conceptions of the Orient, Penguin Books 2014.

[48] S. Hall, The West and…, op. cit., p. 205.

[49] E.W. Said, Orientalism: Western…, op. cit., p. 30.

[50] Goran Azad, personal communication, May 4, 2022.

[51] K. Chomani, Judiciary in Kurdistan Region in Peril, TIMEP 2019, https://timep.org/commentary/analysis/judiciary-in-kurdistan-region-in-peril/, (access 29.11.2024).

[52] S. Rashid, بروسکەنامە- نامەو بروسکەی نێوان مام جەلال، مەسعود بارازانی، نەوشیروان مستەفا: ١٩٩٠-٢٠٠٩ [Bruskanama: The letters and correspondence between Mam Jalal, Masoud Barzani, and Nawshirwan Mustafa, 1990-2009], Nawendi Roshnbiri Ediban 2023.

[53] N. Mustafa, What are the KDP and PUK problems about?, 1995, https://www.kurdipedia.org/default.aspx?lng=1&q=2012083021583136678, (access 14.11.2024).

[54] Mala Bakhtiyar, personal communication, February 23, 2023.

[55] B.H. Arif, KDP-PUK Strategic Agreement and Its Consequences for the Governing System in the KRI, “Journal of Asian and African Studies”, 2024, Vol. 59, Issue 6, pp. 1867–1891, DOI: 10.1177/00219096221146747.

[56] N. Mustafa, What are the…, op. cit.

[57] I created this figure based on the KRI’s political system that has officially been defined through the various laws by the KRI’s parliament.

[58] I created this juxtaposition of informal institutions based on my research and investigations on the existing informal institutions. These institutions are the key ones within the KDP’s and the PUK’s political structures that oversee the politics and economics in the KRI. This is not an overall detailed picture, it is rather a very general one.

[59] M.B. Caggins III, Peshmerga Reforms: Navigating Challenges, Forging Unity, Foreign Policy Research Institute 2023, https://www.fpri.org/article/2023/10/peshmerga-reforms-navigating-challenges-forging-unity/, (access 15.03.2024); S. Aziz, A. Cottey, The Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga: Military reform and nation-building in a divided polity, “Defence Studies”, 2021, Vol. 21, Issue 2, pp. 226–241, DOI: 10.1080/14702436.2021.1888644.

[60] S. Rashid, Resignation of Judge Latif Sheykh Rashid, Radio Nawa 2018, https://www.radionawa.com/ku/wtar-detail.aspx?jimare=476, (access 01.02.2024).

[61] Saro Qadir, personal communication, May 12, 2023.

[62] Stop Organization for Monitoring and Development, Corruption trajectory of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, Report 2022.

[63] Sarkawt Shamsuldin, personal communication, May 26, 2022.

[64] Z. Kopplin, Cowboy Drugstore. Traces of a kleptocrat from Iraq to Delaware to Miami, The American Prospect 2021, https://prospect.org/power/cowboy-drugstore-traces-of-a-kleptocrat/, (access 09.06.2024).

[65] Rewas Fayaq, personal communication, June 9, 2022.

[66] Qubad Talabani, personal communication, June 22, 2022.

[67] Goran Azad, personal communication, May 4, 2022.

[68] Adnan Mufti, personal communication, June, 2023.

[69] Dr. Yousuf Muhammad, personal communication, May 23, 2022.

[70] S. Rasul, The Kurdistan Parliament between the hegemonic political parties culture and voters in the KRI, Kurdistan Times 2024, https://kurdistantimes.org/2024/05/06/227/, (access 05.03.2024).

[71] Goran Azad, personal communication, May 4, 2022.

[72] K. Hassan, Kurdistan’s Politicized Society…, op. cit.

[73] N. Degli Esposti, The 2017 independence referendum and the political economy of Kurdish nationalism in Iraq, “Third World Quarterly”, 2021, Vol. 42, Issue 10, pp. 2317–2333, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2021.1949978.

[74] Dr. Yousuf Muhammad, personal communication, May 23, 2022.

[75] Ibidem.

[76] S. Kurda, Unifying and nationalizing the Peshmerga forces; Key task for KRI Presidency, Sbeiy 2019, https://www.sbeiy.com/Details.aspx?jimare=14863, (access 05.01.2023).

[77] K.F. Dri, Four Western countries send letter to President Barzani on Peshmerga reforms, Rudaw 2022, https://www.rudaw.net/english/kurdistan/161220212, (access 24.06.2022).

[78] F. Fliervoet, Fighting for Kurdistan? Assessing the nature and functions of the Peshmerga in Iraq, Clingendael Institute 2018.

[79] M. Rauf, Money, armed forces and power determine election results. American University in Slemani Forum, 2024, https://www.facebook.com/watch/?ref=search&v=1088982332332630&external_log_id=2d63d079-eed6-45ba-b0f3-865888f150ed&q=هێز%20و%20پارە%20و%20دەسەڵات%20هەڵبژاردن%20یەكلادەكاتەوە, (access 25.04.2024).

[80] Adnan Osman, personal communication, April 16, 2024.

[81] Ibidem.

[82] Rewas Fayaq, personal communication, June 9, 2022.

[83] R. Irvine, MERI Debate on the Referendum for Independence, Middle East Research Institute, 2017, Vol. 4, No. 12, pp. 1–3; H.I. Ahmed, A statement from Hero Ibrahim Ahmed, Kurdsat Facebook Page 2017, https://www.facebook.com/Kurdsat/photos/a.10152294160614390/10155829664144390/?type=3&locale=fr_FR, (access 29.11.2024).

[84] Goran Azad, personal communication, May 4, 2022.

[85] Rebwar Talabani Says I will Not Abide by Court Verdicts, Rudaw 2022, https://www.rudaw.net/sorani/kurdistan/310520229, (access 13.06.2022).

[86] Ibidem; Rebwar Kakayi, personal communication, June 2, 2022.

[87] N. Degli Esposti, The 2017 independence…, op. cit., pp. 2317–2333.

[88] Barzani: If Maliki returns to power, I will declare independence, Rudaw 2017, https://www.rudaw.net/english/kurdistan/230120172, (access 29.11.2024).

[89] H. Mustafa, Barzani threatens referendum in Kurdistan if Maliki gets third term, Asharq Al-Awsat 2014, https://eng-archive.aawsat.com/hamzamustafa/news-middle-east/barzani-threatens-referendum-in-kurdistan-if-maliki-gets-third-term, (access 15.06.2024).

[90] A. Tinti, Oil and National Identity in the KRI: Conflicts at the Frontier of Petro-Capitalism, 1st ed., Routledge 2021, DOI: 10.4324/9781003161103.

[91] N. Wörmer, L. Lamberty, Scattered Dreams: The Independence Referendum, the Fall of Kirkuk and the Effect on Kurdish and Iraqi Politics, International Reports 1/2018, Other Topics, https://www.kas.de/documents/252038/253252/7_dokument_dok_pdf_52122_2.pdf/0a606c42-1abd-1641-9b4d-44d6cd25eca8?version=1.0&t=1539647624437, (access 23.12.2024).

[92] N.S. Khalid, The State of the Institutions of Economic Freedom in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, in: Economic Freedom of the World 2021 Annual Report, eds. J. Gwartney, R. Lawson, J. Hall, R. Murphy, Fraser Institute 2021, pp. 211–236.

[93] Qubad Talabani, personal communication, June 22, 2022; Rewas Fayaq, personal communication, June 9, 2022.

[94] Dr. Niyaz Najmadin, personal communication, May 22, 2022.

[95] KNN TV channel interview, https://www.facebook.com/KNN.KRD/videos/ئەوەى-غیرەتى-هەبێت-و-نیشتمان-پەروەربێت-دەبێت-چەک-هەڵبگرێت-دژى-بڕیارەکانى-دادگاى-/347293347557084/?locale=ms_MY, (access 18.11.2023).

[96] Ibidem.

[97] Ali Hussein, personal communication, 21 February 2023.

[98] S. Aziz, B. Wahab, Family Rule in Iraq and the Challenge to State and Democracy, Policy Analysis 2023, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/family-rule-iraq-and-challenge-state-and-democracy, (access 20.04.2024).