Cezary Smuniewski, Tomasz Kamiński

Full Article: View PDF

How to cite

Smuniewski C., Kamiński T., Patriotism as Understood by Polish Secondary School Graduates: A National Defense Perspective, “Polish Journal of Political Science”, 2025, Vol. 11, Issue 4, pp. 22–34, DOI: 10.58183/pjps.02042025.

ABSTRACT

The article presents the results of a quantitative study examining how Polish secondary school graduates (matura students) understand patriotism in the context of national defense. The study was conducted in 2025 using an online survey (CAWI) on a sample of 267 respondents over the age of 18 (Polish matura graduates). Assuming that patriotism encompasses both love of the homeland and the responsibility for its well-being that follows from it, the analysis focused on the ways in which young people link patriotism with security and readiness for pro-defense activities. Respondents most frequently identified the period of German occupation (1939–1945) as the culminating moment of patriotism in Polish history (53%), which suggests a strong anchoring of patriotic imaginaries in wartime and martyrological narratives. The results indicate that the respondents associate patriotism to a much greater extent with symbolic and cultural practices – such as respect for national symbols, the cultivation of tradition, and knowledge of history – than with actions of a military nature. Although 72% of respondents consider readiness to fight and to sacrifice one’s life for the homeland to be a patriotic attitude, only 47% associate patriotism with willingness to undertake voluntary military training. The findings are diagnostic in nature and point to the need for further comparative and longitudinal research on transformations in the understanding of patriotism among younger generations and their implications for state security.

Keywords: patriotism, youth, national defense, national security, Poland

Introduction

Patriotism has the capacity to mobilize and motivate citizens to undertake actions for the benefit of the homeland, and when appropriately directed, it may contribute to strengthening broadly understood national security, the provision of which constitutes the most important task of state authorities. It is therefore an idea with the potential to shape social attitudes, and examining its mechanisms may facilitate its use as a resource supporting both national defense and the resilience of the community in the face of threats. For this reason, we undertook an attempt to examine how the young generation of Poles understands patriotism and what significance they attribute to it in the context of national security. This generation will soon co-create civil society, constitute the defensive potential of the state, and determine the directions of its future development.

The aim of this article is to present the results of a study conducted among Polish youth (matura graduates in 2025 aged over 18) concerning their understanding of patriotism in the context of the defense of the Polish state. For the purposes of this analysis, we adopted the assumption that patriotism denotes all forms of love for the homeland, understood both as a place of origin and/or residence, as well as for what is national in character – history, tradition, language, and landscape – which, in the face of threat, should be subject to defense. Underlying this definition of patriotism is the thought of John Paul II, expressed in the book “Memory and Identity: Conversations at the Dawn of a Millennium,”[1] in which the Pope links “love” with the defense of the good that the homeland represents: “Every danger that threatens the overall good of our native land becomes an occasion to demonstrate this love.”[2] Love, therefore, is not a passive disposition but becomes, in human life, a capacity for action. This understanding of emotion and its consequences – here, defensive actions undertaken on behalf of the homeland – is consistent with the broader intellectual framework of this thinker. It is reflected, for example, in the title of his book published in Poland in 1960, when he was still working at the Catholic University of Lublin – “Love and Responsibility.”[3] In Wojtyła’s understanding, later reaffirmed during his papacy, love is inseparably linked with responsible action. In the case of patriotism, this responsibility manifests itself in the defense of the homeland. Following this line of thought, we sought to examine how Polish youth understand patriotism and in what ways they associate it with readiness to defend the state.

This study presents the results of quantitative research conducted in 2025 using an online survey (CAWI) on a sample of 267 respondents. A valuable source of inspiration for the design of the study was the set of questions developed and previously used by the Centre for Public Opinion Research (CBOS).[4] We adopted the assumption that the understanding of patriotism undergoes transformations within society and that its analysis requires the inclusion of a temporal perspective. By applying this research approach, we sought to answer the following question: how do Polish young people understand patriotism in the context of the defense of the homeland?

State of Research, Methodology, and Research Process

With regard to the state of research on patriotism, our analysis is situated against the background of the work of Polish thinkers and scholars who have addressed this concept. Particularly noteworthy are studies produced within the milieu of Polish Catholic intellectuals and researchers, including Józef Maria Bocheński,[5] Jacek Salij,[6] and Jerzy Lewandowski.[7] Within the Polish academic community, scholarship on patriotism has also included works that systematize the phenomenon,[8] examine it from historical[9] and social perspectives,[10] and link it to issues of national security.[11] These studies indicate that identifying as a patriot correlates with increased participation in political and social activities. Expanding the perspective beyond Poland, it is also important to refer to the research of Leonie Huddy and Nadia Khatib, who observe that in the United States, patriotism is often associated with national identity, which in turn motivates individuals to engage actively in the civic life of their country.[12] Patriotism often translates into motivation for action, a relationship also explained by Qiong Li and Marilynn B. Brewer, who, in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, highlighted the strong link between patriotism and national identification, which in turn encouraged citizens to engage in various forms of civic activity.[13] Another important aspect concerns the ways in which patriotism shapes social relations and influences attitudes toward other groups. Research by Thomas Blank and Peter Schmidt demonstrates that differences in the perception of patriotism among German citizens – both in East and West Germany – affect attitudes toward minorities, underscoring that patriotism may promote either tolerance or intolerance depending on the context.[14] Patriotism can also mobilize individuals to act in times of crisis. For example, Despina M. Rothì, Evanthia Lyons, and Xenia Chryssochoou argue that a strong sense of national belonging and patriotism may lead to greater citizen engagement in supportive actions during difficult times, which in turn contributes to the formation of strong social bonds and a shared sense of national community.[15] The associations between patriotism and citizens’ participation in political and social activities identified in previous research prompted us to conduct a study within Polish society, focusing specifically on matura students. We considered this social group – standing at the threshold of adulthood and entering adult life – to be a particularly relevant object of analysis, as their attitudes and understanding of patriotism are likely to influence the development of Poland’s social resilience and defensive potential in the near future.

The study that constitutes the basis of this article was situated within theories of social attitudes and national identity, which conceptualize patriotism as an element of collective memory and the construction of state identity. In this context, we treat the patriotism of matura students as a factor shaping respondents’ readiness to engage in pro-defense activities in support of national security, both in symbolic and behavioral dimensions. Data were collected using an online questionnaire (CAWI – Computer-Assisted Web Interview) distributed to randomly selected secondary schools across Poland. The survey link was sent by email to school administrative offices with a request to forward it to students in their final year of secondary education. The questionnaire consisted of fourteen questions, the last of which was an open-ended question. Data collection lasted 50 days – from January 15 to March 5. A total of 267 matura students aged over 18 participated in the study. For data analysis, we applied meaning coding, meaning condensation, and meaning interpretation, following the approach proposed by Steinar Kvale.[16] We assumed that the data reflect the individual attitudes of matura students and allow for the identification of dominant tendencies in their understanding of patriotism. The sample was not representative. The principal value of our research lies in its exploratory and cognitive character.

Research Findings: Patriotism among Polish Secondary School Graduates

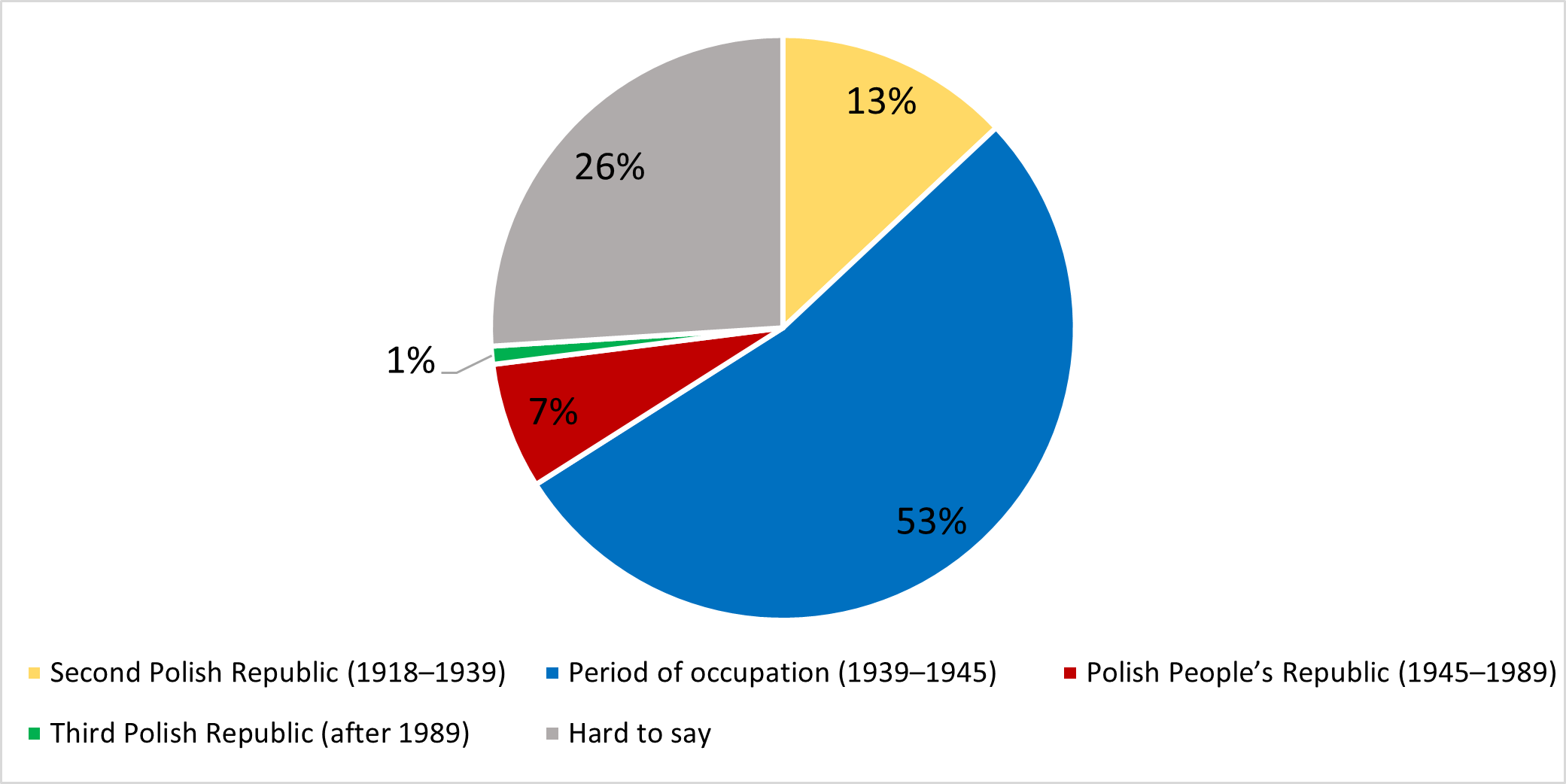

In the survey, participants were asked the following question: “In your opinion, when did Poles demonstrate the greatest level of patriotism?”[17] It should be noted that this question was adopted from earlier research conducted by the CBOS. Respondents – similarly to those participating in the CBOS study – were able to select one historical period from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The available options included: “The Second Polish Republic (1918–1939),” “the occupation of Poland (1939–1945),” “the Polish People’s Republic (1945–1989),” and “the Third Polish Republic (after 1989).” Undecided respondents could also choose the answer “Hard to say.”[18] In posing this question, we were guided by the assumption that the understanding of patriotism does not develop in a social vacuum but rather emerges in dialogue with collective memory and narratives about the past. Asking matura students to assess the patriotism of previous generations makes it possible to identify which historical models serve as sources of inspiration for them and which are subject to critical reassessment. This, in turn, facilitates an understanding of whether they treat patriotism as a value transmitted from generation to generation or rather as an idea that requires redefinition under contemporary socio-political conditions. The inclusion of this perspective therefore enabled a more nuanced understanding of how collective memory and narratives of the past shape current interpretations of patriotism and its relationship to national defense.

Figure 1. Assessment of the Patriotism of Previous Generations of Poles. In your opinion, when did Poles demonstrate the greatest patriotism? During which period:

Source: Own study.

More than half of the surveyed matura students – specifically 53% – identified the period of occupation (1939–1945) as the time when Poles demonstrated the greatest level of patriotism. The second most frequently indicated period was the Second Polish Republic (1918–1939), selected by 13% of respondents. The third most commonly indicated period was the era of the Polish People’s Republic (1945–1989), with 7% of responses, while the least frequently selected was the contemporary period of the Third Polish Republic (after 1989), chosen by only 1% of respondents. More than one quarter of the surveyed youth – 26% – did not select any of the four historical periods listed, instead choosing the response “Hard to say.”

The results indicate that the patriotic imagination of matura students is clearly anchored in a historical, wartime, and martyrological narrative. More than half of the respondents (53%) identified the period of occupation from 1939 to 1945 as the time when Poles demonstrated the greatest patriotism, which suggests that patriotism is primarily associated with situations of extreme threat to the nation’s existence – war, occupation, underground resistance, uprisings, and the sacrifice of life. This is precisely the image that is frequently reproduced in school education, popular culture, and intergenerational transmission. Within these narratives, patriotism is linked not only to heroism, armed struggle, or readiness for self-sacrifice, but above all to resistance against an external enemy. The second most frequently indicated period was the Second Polish Republic (1918–1939), which may suggest that patriotism understood as the construction of social institutions and the development of the state is less strongly present in the awareness of young people than narratives centered on struggle and sacrifice. There is little doubt that the effort to rebuild the state after regaining independence and to consolidate its structures remains overshadowed by the experience of the Second World War in the respondents’ assessments. This may be due to the fact that war-related events are more emotionally charged and therefore more easily embedded in collective memory. The relatively low proportion of responses referring to the Polish People’s Republic (7%) may be explained by the ambiguity of this period, which encompasses both organized social resistance (e.g., the activities of the “Solidarity” movement) and the reality of a non-sovereign state dependent on the political influence of the Soviet Union. The contemporary period of the Third Polish Republic was selected least frequently, indicating that young people do not perceive distinct manifestations of patriotism in times of peace and stability. This may suggest that patriotism is understood by respondents as something historical – associated with past national liberation struggles – rather than with the everyday functioning of the state, such as paying taxes, caring for social institutions, or engaging in civic activities. It is also worth noting that as many as 26% of respondents selected the answer “Hard to say,” which may reflect both gaps in historical knowledge and a certain distance from traditional patriotic narratives.

In summary, the results suggest that the patriotic imagination of matura students is strongly anchored in wartime and martyrological narratives (the occupation of 1939–1945), with a relative appreciation of the period of the Second Polish Republic and a very limited presence of postwar and contemporary forms of patriotism. At the same time, the substantial proportion of “Hard to say” responses points to uncertainty, ambivalence, or a more nuanced understanding of patriotism that does not easily fit into a simple classification of a “most patriotic period.”

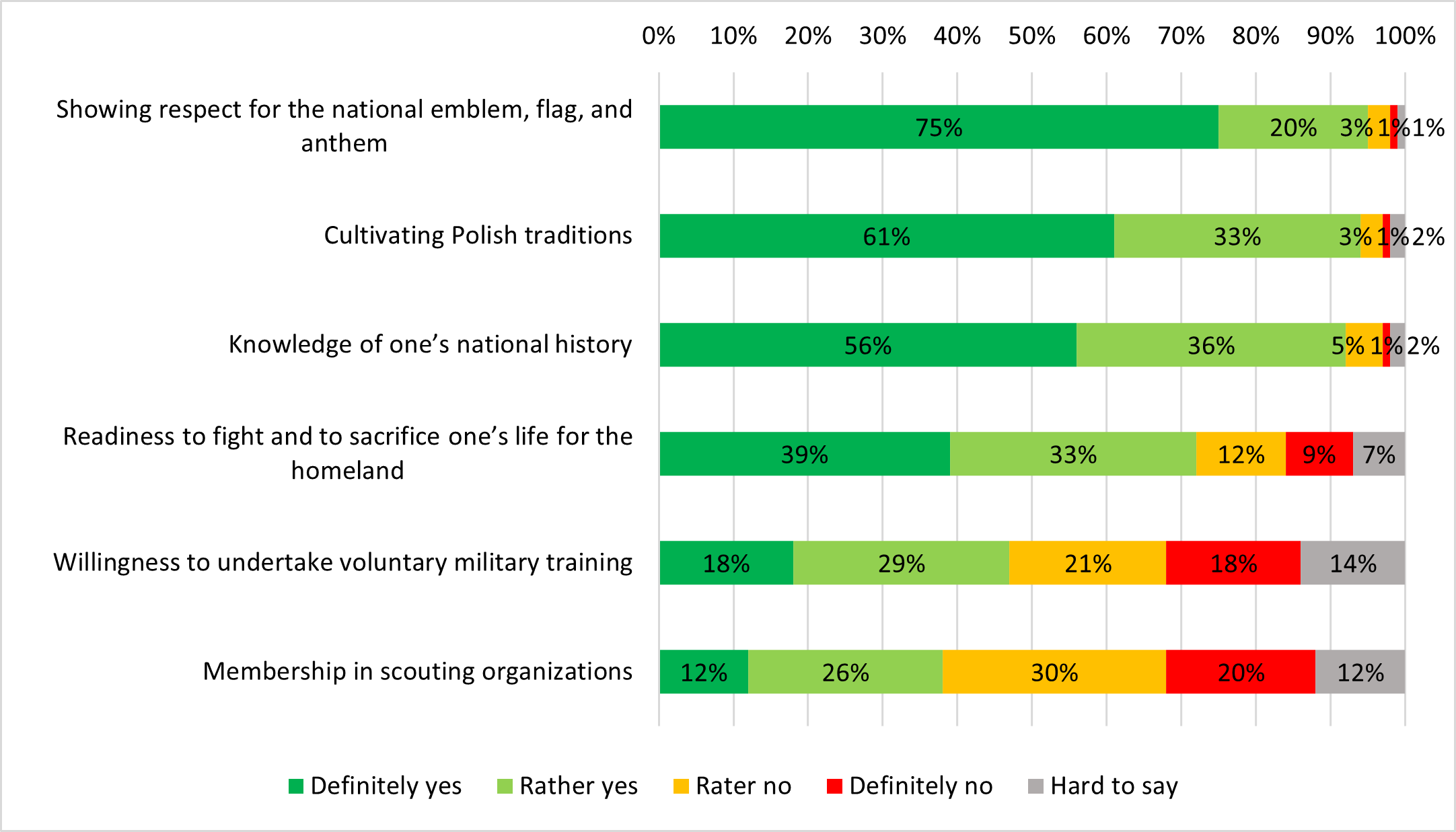

The next question posed to respondents was as follows: “Patriotism is attributed various meanings. In your opinion, does patriotism consist in:.” In incorporating this question into our survey questionnaire, we drew on a study conducted by the CBOS in 2018.[19] However, given the adopted research perspective, we decided to use only six variables out of the fourteen applied by CBOS researchers. Using a Likert scale, respondents were asked to assess the importance of the following potential components of patriotism: showing respect for the national emblem, flag, and anthem; cultivating Polish traditions; knowledge of the country’s history; readiness to fight and sacrifice one’s life for the homeland; willingness to undertake voluntary military training; and membership in scouting organizations (e.g., the Polish Scouting and Guiding Association – ZHP – and the Polish Scouting Association – ZHR). The selection of these variables was guided by their direct relevance to issues related to national defense, which constituted the core focus of our analysis.

Figure 2. Attitudes Associated with Patriotism. Patriotism is attributed various meanings. In your opinion, does patriotism consist in:

Source: Own study.

Showing respect for the national emblem, flag, and anthem was indicated by as many as 95% of respondents, of whom 75% selected the answer “definitely yes” and 20% “rather yes.” Only 4% of matura students believed that patriotism does not involve showing respect for national symbols (3% “rather no” and 1% “definitely no”), while 1% chose the response “hard to say.” In the case of cultivating Polish traditions, 94% of respondents considered this to be an element of patriotism, including 61% who answered “definitely yes” and 33% “rather yes.” Only 4% of participants did not recognize the cultivation of Polish traditions as an expression of patriotism (3% “rather no” and 1% “definitely no”), while 2% selected “hard to say.” Knowledge of one’s national history was regarded as important by 92% of respondents, with 56% choosing “definitely yes” and 36% “rather yes.” Only 6% expressed the opposite view (5% “rather no” and 1% “definitely no”), and 2% again selected “hard to say.” Readiness to fight and to sacrifice one’s life for the homeland was identified as patriotic by 72% of respondents (39% “definitely yes” and 33% “rather yes”). However, 21% did not consider such behavior to be an expression of patriotism (12% “rather no” and 9% “definitely no”), while 7% of matura students selected “hard to say.” Willingness to undertake voluntary military training was considered patriotic by only 47% of respondents, including 18% who answered “definitely yes” and 29% “rather yes.” As many as 39% of participants did not regard this attitude as an expression of patriotism (21% “rather no” and 18% “definitely no”), while 14% selected “hard to say.” Membership in scouting organizations was associated with patriotism by 38% of respondents, including 12% who selected “definitely yes” and 26% “rather yes.” Half of the respondents did not consider being a scout to be an expression of love for the homeland (30% “rather no” and 20% “definitely no”), while the remaining 12% chose the option “hard to say.”

The results presented in Figure 2 reveal a clear differentiation in the ways matura students understand patriotism. The data indicate that young people perceive patriotism primarily as attachment to symbols, traditions, and history, while far less frequently associating it with military practices. This pattern suggests that patriotism is viewed mainly as a cultural and identity-based value, rather than as a practice requiring tangible sacrifice or participation in organized forms of social life, such as scouting. It is worth noting that, in the eyes of matura students, patriotism is on the one hand deeply rooted in culture and history, and on the other hand subject to reinterpretation, in which heroism and institutionalized forms give way to a more multidimensional and diverse understanding of civic responsibility.

Conclusion

The aim of this article was to identify how Polish matura students understand patriotism from the perspective of national defense and how they relate it to national security and readiness for pro-defense activities. The presented findings indicate a distinct profile of meanings: within the studied group, patriotism is primarily a cultural and identity-based category, strongly embedded in collective memory and national symbolism, while to a lesser extent it is associated with practices that may be interpreted as preparation for concrete defensive tasks.

First, the patriotic imagination of respondents is strongly anchored in wartime and martyrological narratives. The dominant indication of the period of occupation (1939–1945) as the culmination of patriotism in Polish history suggests that, in the consciousness of young people, patriotism is reconstructed primarily through experiences of extreme threat and heroic resistance. This anchoring is analytically significant: the preferred “patriotic models” are not neutral references to the past but constitute an interpretive resource that shapes which forms of engagement are recognized as authentically patriotic and which remain marginalized or are regarded as secondary. Second, responses to questions concerning the components of patriotism reveal a consistent pattern: a high level of acceptance of symbolic components (respect for the flag, emblem, and anthem) and cultural components (the cultivation of tradition and knowledge of history) coexists with a relatively weaker association of patriotism with preparatory and institutional activities (voluntary military training and scouting). Particularly significant is the tension between the frequent recognition of readiness to fight and to sacrifice one’s life for the homeland as a patriotic attitude and the much less frequent association of patriotism with voluntary military training. From a sociological perspective, this may indicate a model of patriotism in which heroism and declared willingness to sacrifice are more strongly legitimized than preparation, competencies, and practices that increase agency in situations of threat. From the perspective of national defense, this distinction is crucial: social mobilization requires not only declarations of values but also readiness to participate in activities that make such mobilization practically possible.

These results do not justify simple normative judgments or far-reaching predictions regarding behavior under conditions of threat to the security of the Republic of Poland. They do, however, allow for a diagnostic conclusion: within the studied group, patriotism understood as identity and a symbolic bond with the community prevails over patriotism understood as preparation and the practice of civic responsibility in the pro-defense dimension. If this profile were to persist in the broader population of young adults, it could indicate the existence of a gap between declared values and the willingness to undertake activities that require time, discipline, and competencies (such as training, forms of service, or membership in organizations). From the perspective of public policy and security education, this constitutes a signal that efforts aimed at strengthening social resilience should integrate an axiological component (identity, community, memory) with a practical component (skills, participation, social institutions), so that patriotism does not remain confined solely to the realm of symbols and narratives.

The article also has clearly defined limitations. The sample was not representative, and the indicators applied measure declarations and assessments of meanings rather than actual behaviors or pro-defense competencies. Moreover, a limited set of variables inspired by CBOS research was used, which brings analytical order but at the same time narrows the range of possible interpretations. For this reason, the results should be treated as exploratory findings, useful primarily for formulating hypotheses and designing subsequent stages of research. Further research should proceed in three main directions. First, comparative and longitudinal studies are needed to capture the dynamics of change in the understanding of patriotism over time and to distinguish generational effects from the influence of the current socio-political context. Second, it would be valuable to supplement the findings with a qualitative component in order to more precisely reconstruct the meanings that respondents assign to categories such as “readiness to fight,” “responsibility,” “training,” and “educational organizations.” Third, it is advisable to incorporate differentiating variables into analytical models (including family background, local environment, social capital, exposure to security education, and understandings of peace), which would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms shaping attitudes and identifications.

In conclusion, the presented study shows that among Polish matura students, patriotism is primarily a sphere of symbols, traditions, and historical memory, and to a lesser extent a sphere of practices preparing individuals for pro-defense activities. From the perspective of state security, this conclusion is significant not as a diagnosis of a “deficit of patriotism,” but rather as an indication of a specific type of patriotism that predominates within the studied group. A better understanding of this profile – and of how it may evolve – is a prerequisite for designing effective educational and social initiatives that strengthen both community cohesion and the capacity for responsible action in situations of threat.

References

[1] John Paul II, Memory and Identity: Conversations at the Dawn of a Millennium, transl. by A. Walker, Rizzoli 2005.

[2] Ibidem, pp. 65–66.

[3] K. Wojtyła, Love and Responsibility, transl. G. Ignatik, Pauline Books & Media 2013.

[4] CBOS – Centre for Public Opinion Research, one of the largest public opinion research centers in Poland, established in 1982, largely financed from public funds.

[5] J.M. Bocheński, Katastrofa pacyfizmu, Wydawnictwo ANTYK Marcin Dybowski 1989; J.M. Bocheński, Patriotyzm, Męstwo, Prawość żołnierska, Wydawnictwo ANTYK Marcin Dybowski 2006.

[6] J. Salij, Patriotyzm dzisiaj, Wydawnictwo Polskiej Prowincji Dominikanów „W drodze” 2005.

[7] J. Lewandowski, Naród w nauczaniu kardynała Stefana Wyszyńskiego, Wydawnictwo Archidiecezji Warszawskiej 1989.

[8] C. Smuniewski, Wychowanie do patriotyzmu. Studium o miłości ojczyzny w oparciu o biblijną i współczesną myśl katolicką, in: Bezpieczeństwo jako problem edukacyjny, eds. A. Pieczywok, K. Loranty, Wydawnictwo AON 2015, pp. 84–103; A. Walicki, Trzy patriotyzmy: trzy tradycje polskiego patriotyzmu i ich znaczenie współczesne, Res Publica 1991.

[9] J. Kloczkowski (ed.), Z dziejów polskiego patriotyzmu: wybór tekstów, Ośrodek Myśli Politycznej: Wyższa Szkoła Europejska im. ks. J. Tischnera 2007; J. Kloczkowski (ed.), Patriotyzm Polaków: studia z historii idei, Ośrodek Myśli Politycznej 2006; J. Kurczewska, Patriotyzm(y) polskich polityków: z badań nad świadomością liderów partyjnych lat dziewięćdziesiątych, Wydawnictwo Instytutu Filozofii i Socjologii PAN 2002.

[10] A. Wiłkomirska, A. Fijałkowski, Jaki patriotyzm?, Difin SA 2016; C. Smuniewski, “I saw the way the Gospel changes a man”. God, man and Homeland in the daily life of Fr. Jerzy Popiełuszko, transl. A. Bartosiak, O. Kurzyk, R. Clarke, in: Jerzy Popiełuszko. Son, Priest, Martyr from Poland, eds. P. Burgoński, C. Smuniewski, Wydawictwo “Sióstr Loretanek” 2016, pp. 117–134; H. Woźniakowski, Patriotyzm aktualnego etapu, Znak 2010, https://www.miesiecznik.znak.com.pl/6642010henryk-wozniakowskipatriotyzm-aktualnego-etapu/, (access 28.10.2025); J. Staniszkis, Patriotyzm współczesnych Polaków oczami socjologa, in: Patriotyzm polski. Jaki jest? Jaki winien być?, eds. A. Kozłowska, Światowy Związek Żołnierzy Armii Krajowej, Oficyna Wydawnicza Rytm 2001, pp. 59–65; S. Ossowski, O ojczyźnie i narodzie, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe 1984.

[11] C. Smuniewski, Ku identyfikacji współczesnej drogi miłośnika ojczyzny. Z badań nad tożsamością i patriotyzmem w tworzeniu bezpieczeństwa narodowego Polski, in: Powrót do Ojczyzny? Patriotyzm wobec nowych czasów. Kontynuacje i poszukiwania, eds. C. Smuniewski, P. Sporek, Oficyna Wydawnicza ASPRA-JR, Wydawnictwo Instytutu Nauki o Polityce 2021, pp. 19–50; C. Smuniewski, Na drogach krzewienia miłości Ojczyzny. Patriotyzm jako fundament bezpieczeństwa narodowego, in: Klasy mundurowe. Od teorii do dobrych praktyk, eds. A. Skrabacz, I. Urych, L. Kanarski, Wydawnictwo AON 2016, pp. 39–51; J. Marczak, et al., Doświadczenia organizacji bezpieczeństwa narodowego Polski od X do XX wieku. Wnioski dla Polski w XXI wieku, Akademia Obrony Narodowej 2013; K. Gąsiorek, W.S. Moczulski (eds.), Patriotyzm fundamentem bezpieczeństwa narodowego RP w XXI wieku, Stowarzyszenie Ruch Wspólnot Obronnych 2011; E.A. Wesołowska, A. Szerauc (eds.), Patriotyzm, obronność, bezpieczeństwo: praca zbiorowa, Akademia Obrony Narodowej 2002.

[12] L. Huddy, N. Khatib, American Patriotism, National Identity, and Political Involvement, “American Journal of Political Science”, 2007, Vol. 51, Issue 1, pp. 63–77, DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00237.x.

[13] Q. Li, M.B. Brewer, What Does It Mean to Be an American? Patriotism, Nationalism, and American Identity After 9/11, “Political Psychology”, 2004, Vol. 25, Issue 5, pp. 727–739, DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00395.x.

[14] T. Blank, P. Schmidt, National Identity in a United Germany: Nationalism or Patriotism? An Empirical Test With Representative Data, “Political Psychology”, 2003, Vol. 24, Issue 2, pp. 289–312, DOI: 10.1111/0162-895x.00329.

[15] D.M. Rothì, E. Lyons, X. Chryssochoou, National Attachment and Patriotism in a European Nation: A British Study, “Political Psychology”, 2025, Vol. 26, Issue 1, pp. 135–155, DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00412.x.

[16] S. Kvale, Doing Interviews, SAGE Publications 2007, pp. 101–119.

[17] M. Feliksiak, Rozumienie patriotyzmu – Komunikat z badań nr BS/167/2008, CBOS 2008, p. 7.

[18] Ibidem.

[19] A. Głowacki, Patriotyzm Polaków – Komunikat z badań nr 105/2018, CBOS 2018, p. 7.