Rossi Selvaggi III

Lipton Matthews

Walter E. Block

Full Article: View PDF

How to cite

Selvaggi R., Matthews L., Block W.E., Should We Have the Minimum Wage at All? A Political Economic Analysis, “Polish Journal of Political Science”, 2024, Vol. 10, Issue 3, pp. 72–89, DOI: 10.58183/pjps.04032024.

ABSTRACT

Minimum wage laws are touted as an instrument to improve compensation for labor, particularly for the unskilled. However, by increasing wages above market levels, they reduce the demand for labor and dampen the prospects of job seekers. Such laws create a disincentive for corporations to employ low-skilled workers, thereby limiting opportunities for human capital acquisition. Therefore, the minimum wage has the reverse effect of harming rather than uplifting workers. Because this law does not achieve its stated objective, it should be abolished to allow the market to allocate labor and resources efficiently. We do not merely oppose an increase in the minimum wage level proscribed by law, nor do we favor the status quo in this regard. Nor do we call for a decrease in the legally mandated wage. Instead, we make the case that this pernicious legislation should be eliminated root and branch.

Keywords: minimum wage, unemployment, hypocrisy

Introduction

Should we have the minimum wage at all? The simple answer is no. The purpose of this article is to explore the effects of this legislative enactment. The thesis of the present essay is that, despite the positive spin engendered by the very title of this law (no decent person can oppose raising worker compensation), minimum wages have the opposite effect: instead of increasing remuneration, they exacerbate unemployment. Our research hypothesis is that this regulation remains popular due to the lack of economic sophistication not only among the general public but also among legislators, who really ought to know better.

In Section II, we examine the unintended effects of wage minima imposed by legislation. Section III discusses the crucial role of productivity. Section IV focuses on the unemployment effects of this law. Racial discrimination rears its ugly head in Section V. In Section VI, we consider and reject several arguments in favor of minimum wage legislation. A critique of the one-size-fits-all nature of this legislation is the subject of Section VII. We address loopholes in Section VIII, analyze ethical considerations in Section IX, and, in Section X, examine the case of California within this context. Section XI presents our conclusion.

Unintended Effects

The real tragedy of minimum wage laws is that they are supported by well-meaning groups who want to reduce poverty. However, the people most hurt by higher minimum wages are the most poverty-stricken.[2] Minimum wage laws have a nice ring to them; who wouldn’t want more money for the same job? Sign us up! If only it were that easy to increase everyone’s wages without negative consequences. Our aim is not to criticize the intentions of those who set these minimum wage laws in place but to demonstrate their unintended consequences using the logic of productivity and wages. In this paper, we discuss the economic principles behind minimum wage laws and explore the various ways these laws undermine the poor.

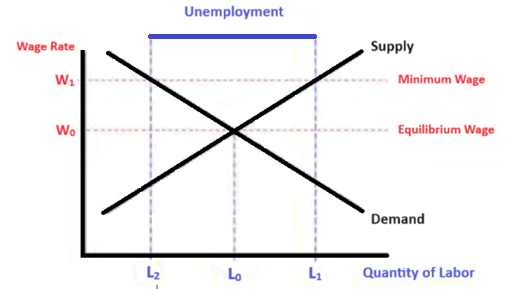

Based on the basic supply and demand curve of the supply of labor,[3] creating a minimum wage would increase the cost of labor and reduce the demand for it. In the absence of a minimum wage, the salary paid to the average worker would be W0, and L0 workers would be hired. We now introduce a mandated wage of W1>W0. At this higher wage, L2<L0 laborers will find employment, an additional L1-L0 will seek jobs, and the unemployed will be measured by L1-L2.

Figure 1. Wage Rates and Quantity of Labor

Source: Own study.

This demand reduction will cause unemployment, all other things equal. When the price of labor (wages) increases, employers are less likely to hire workers, resulting in fewer job opportunities for those seeking employment. This relationship between wages and the demand for labor is a fundamental economic principle and cannot be ignored when discussing minimum wage laws.

Productivity

Workers are employed and paid wages based on their productivity. When employees increase their productivity through on-the-job training, experience, and other such inputs, their wages rise through promotions and raises over time. Employers and businesses will not, and should not, be required to pay hourly wages greater than the productivity of the worker. By instituting this law, wages are increased without raising productivity. This mismatch creates an issue for employers and employees, causing workers whose hourly productivity is below the level set by this law to become redundant. There is no coherent economic case for any business to pay people more than their productivity, and therefore, unemployment among people with productivity below the minimum wage will increase. This issue is especially detrimental to those with low skills or little experience, as they are precisely the ones most likely to be priced out of the labor market by minimum wage laws.

Based on this, not only should we not raise the minimum wage, but we should also not have it in the first place. The wages of employees should vary just as much as their productivity. One way this can be achieved is by not having a minimum wage and letting the free markets determine wages. When you first get your job, your productivity will be estimated based on past jobs, education, or other experiences. Your wages will be paid based on how much productivity you provide. As you gain experience, training, or other forms of education, your productivity will increase. You can then ask for a raise based on your increased productivity or shop around for employers who believe your productivity may be higher.[4] Letting the free markets decide wages based on productivity, rather than a federal mandate, allows higher-productivity individuals to earn more and lowers unemployment for low-productivity workers. Those with productivity below the minimum wage would normally not be employed but now have the opportunity to work, gain experience, and, in the future, increase their productivity and negotiate for higher wages. With a minimum wage, lower-productivity workers would not be employed and, in turn, would not have a chance to increase their productivity, leading to higher unemployment.

Minimum wage laws unevenly hurt low-productivity workers. They, presumably,[5] were created to help lower-productivity workers, people who tend to come from poorer, less educated backgrounds, and younger people just entering the workforce; however, they do the very opposite. Minimum wage laws hurt the people they were designed to help. High schoolers looking for their first job, ex-convicts re-entering society, and people with disabilities would all be better off without the minimum wage and would be more fully employed. The fast-rising minimum wage has resulted in job losses for young adults, women, and low-skilled workers.[6] These groups often find it more difficult to secure employment, and by having a minimum wage, their opportunities are further limited, creating a cycle of poverty and dependency on government assistance.[7]

Unemployment

Such negative effects of the minimum wage on the labor mobility of low-skilled workers have been studied extensively. On average, most people employed in minimum wage jobs are not from poor families, but they do lack work experience. Hence, when the minimum wage compels employers to compensate these individuals at a rate above their skills, employers are less likely to hire them. Therefore, the curtailment of jobs prevents younger people from advancing on the learning curve. Furthermore, because most recipients of the minimum wage are not from poor families, this policy is an inefficient strategy for helping the poor and could, in fact, increase the probability of long-term poverty.[8] Proponents assert that the minimum wage helps poorer people, but since it forces employers to cut employment, it ultimately redistributes income upwards to those who are more educated and less impoverished.[9] A study from Germany argues that increasing the minimum wage amplifies income inequality and poverty because households at the bottom would lose out due to joblessness.[10]

Furthermore, the allure of higher wages might encourage poorer people to de-enroll from their studies. In an increasingly complex economy, higher-order skills are required, so transferring from school to work will have a negative impact on the long-term wage growth of the poorer classes. An American study reveals that minimum wage increases have a negative effect on community college enrollment, but they do not affect enrollment in four-year colleges.[11] Minimum wages create perverse incentives for poorer people by encouraging them to exchange learning for presumed short-term income growth.[12] Indirectly, the minimum wage also limits funding to the poor by truncating the growth of the non-profit sector. An analysis shows that large statutory minimum wage increases reduce the expansion of non-profit enterprises.[13]

Compensating workers above productivity levels sounds appealing to some, but it is not economically efficient and should not be required by law. Indeed, many employers offer lucrative salaries to employees in the absence of minimum wage laws. One example of this can be found at Bitty and Beau’s, a coffee shop that employs people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, where the employees are paid above the minimum wage based on the business owner’s compassion and understanding of their unique circumstances. This highlights that employers can still choose to pay their employees more than their productivity warrants out of a sense of social responsibility or to create a positive workplace environment. However, making it a legal requirement can have negative effects on the labor market and the economy as a whole.

The impact of minimum wage laws can be compared to rent control. Both policies are intended to help lower-income individuals but often have unintended consequences. Rent control can lead to housing shortages and deteriorating conditions as landlords have less incentive to maintain their properties.[14] Similarly, minimum wage laws can lead to job losses and reduced opportunities for low-skilled workers. In both cases, the policies may initially seem beneficial to the target population, but in the long run, they often exacerbate the problems they were intended to solve.

Racial Discrimination

Minimum wage laws also contribute to more discrimination due to the lack of free enterprise in determining who gets the fewer jobs remaining. As Caleb Fuller writes, “When you have a surplus of labor in a market with a minimum wage, prices aren’t allowed to adjust, so the employer picks from that surplus based on personal preferences. These may include race, sex, gender, religion, or other personal characteristics that have little to do with productivity. In fact, in the past, it has included just that.”[15] This suggests that minimum wage laws may inadvertently create an environment where employers are more likely to discriminate based on non-productivity-related factors, further limiting opportunities for marginalized groups in the workforce.

Consider the following argument: without minimum wage laws, workers would be paid unlivable wages. These wages are better than the income from not having a job at all. Employment with poor wages at least allows workers to gain experience, skills, and training to increase productivity “…the increased willingness of low-skilled workers to offer services for hire will be irrelevant to the actual results, because fewer jobs will be available. Rather than being able to sell more services at higher wages, they will actually be able to sell fewer services, and some will be completely priced out of jobs, earning nothing.”[16] Additionally, competitive market forces would likely prevent employers from paying extremely low wages, as they would struggle to attract and retain employees. Instead, wages would be determined by the productivity and value the worker brings to the company, creating a more efficient and equitable labor market.

Defenses Refuted

Here is an argument in behalf of the minimum wage: Raising it would act as a wave and bring everyone’s wages up. Even if it causes some unemployment, the gains for others would be able to cover the unemployed through social programs.

However, allowing an increase in unemployment and using welfare as a crutch will not give the lower-productivity worker who is unemployed an opportunity to increase their productivity through work experience. This will continue a cycle of unemployment and create a disincentive to become a working member of society, regardless of productivity level. A Cato Institute study found that “In the 21 countries with a minimum wage, the average country has an unemployment rate of 11.8%. Whereas, the average unemployment rate in the seven countries without mandated minimum wages is about one third lower — at 7.9%.”[17] This study shows that the absence of a minimum wage actually decreases the unemployment rate. Another finding of this study was that the unemployment rate for youth in countries with a minimum wage was significantly higher than in those without. “In the twenty-one E.U. countries where there are minimum wage laws, 27.7% of the youth demographic — more than one in four young adults — was unemployed in 2012. This is considerably higher than the youth unemployment rate in the seven E.U. countries without minimum wage laws — 19.5% in 2012.”[18]

This study suggests that not only does the minimum wage cause more unemployment, but it specifically causes more unemployment among youth groups. This finding is significant because youth, a group that is targeted to be helped by the minimum wage due to their typically lower productivity per hour from lack of experience and/or education, are actually the ones being hurt. Additionally, even if wage increases lead to short-term benefits, their costs will eliminate these benefits in the long term.[19]

Another argument for the minimum wage is that it provides a basic level of income that helps lift low-wage workers and their families out of poverty. While minimum wage laws may help some workers,[20] they also lead to unemployment and reduced opportunities for others, particularly those with the lowest productivity levels. The American Action Forum’s research found that “increasing the minimum wage actually has a devastating impact on job markets in the United States” when holding education constant and taking into account all 50 states. Moreover, minimum wage laws can create a disincentive for workers to improve their skills, as they may become reliant on the mandated wage floor rather than striving to increase their productivity and, in turn, their earning potential.

One Size Fits All

The concept of a minimum wage imposes a one-size-fits-all approach to an incredibly diverse labor market, disregarding the unique circumstances of different industries, regions, and individuals. This blanket solution fails to account for the variability in living costs and productivity levels, ultimately creating mismatches in the labor market. The most efficient approach would be to allow wages to naturally adjust according to local conditions, ensuring that workers are paid according to their true value in the market. That is to say, the market is always and ever tending in the direction of wages equal to marginal revenue productivity. If MRP is $10 and wages are $15, the employer will lose money, and if they persist, they will go bankrupt. If wages are $7, the firm will earn a pure profit of $3 per hour; some other company will offer $7.01, another $7.02, etc. Where will this process end? At exactly a wage of $10, provided there are no transaction costs.

Minimum wage laws can also hinder the entrepreneurial spirit and the creation of new industries and jobs. Small businesses often operate on thin profit margins and can struggle to absorb the increased labor costs imposed by minimum wage requirements. As a result, these smaller businesses may be forced to reduce their workforce or halt expansion plans, limiting job opportunities and future growth. By removing the minimum wage, businesses would have more flexibility to allocate resources and adapt to market conditions, creating an environment that encourages innovation and job creation.

Loopholes

The question must be asked: why do we need a minimum wage when we already have gaps in our economy? Unpaid interns are allowed, and the companies that hire them are not persecuted. These companies are benefitting from the labor of the interns and, in return, pay them nothing financially. While critics of this point could describe all the positive benefits received by the intern, including hands-on experience, education, and networking, exactly the same could be said of an employee who earns less than the level stipulated by law. Why is that the threshold or zero? Companies would be sued out of existence if they started paying their employees 25 cents an hour, but several companies, churches, and political campaigns happily pay interns exactly nothing. Why would the companies paying something, but less than this minimum, be punished, while the organizations not paying for services at all are not being punished? In addition, unpaid internships unequally favor the more economically well-off because they will be more likely to have the funding to work for free. This causes even more of an income disparity between the rich and the poor.

Although mostly well-intentioned,[21] minimum wage laws have unforeseen consequences that often hurt the very people they aim to help. By creating unemployment and reducing opportunities for low-skilled workers, these laws can worsen poverty rather than reduce it. Eliminating the minimum wage and allowing the free market to determine wages based on productivity would provide more opportunities for all workers, regardless of their current skill level, to gain experience, improve their productivity, and ultimately increase their earnings. A market-driven approach would provide a more efficient and equitable labor market, where workers are rewarded for their contributions to the economy and have the incentive to continuously develop their skills and abilities.

Ethics

There is also the matter of ethics that must be considered. Bernie Sanders wants the minimum wage to be set at $15 per hour. So, if A offers to pay B $12 per hour for a job, and B accepts, they both could be incarcerated for violating this law. This goes against Robert Nozick’s insightful support for “capitalist acts between consenting adults.”[22] The idea that people should be put in jail for a voluntary commercial agreement stretches credulity from a moral point of view.

Then, too, it is not exactly ethical to support a law that attacks “the least, the last, and the lost” of us by rendering unemployable those workers at the bottom of the economic pyramid, the ones with the lowest skills and, hence, productivity.

State of California

The state of California is the venue of the most recent controversy over the minimum wage law. Several researchers have not found any increase in unemployment among unskilled workers, or anyone else for that matter. For example, according to An Economic Sense: “But what is clear and significant is that aggressive increases in the minimum wage in California have not led to increases in unemployment in the state. The assertion that they would is simply wrong.”[23]

In our view, these are necessary results. If the minimum wage rises, say, from $12 to $16 per hour, then all those whose productivity lies between those two levels will eventually become not only unemployed but unemployable. Consider a person who can raise the receipts of his employer by $13 per hour. He can earn $1 per hour for his boss; however, if he must be paid at the new level of $16, he will impose a loss of $3 every sixty minutes. If many like him are hired, the company will go bankrupt.

The failure to find evidence of this phenomenon may be due to the fact that it takes time for economic effects to work their way through the economy. It is akin to searching for triangles with 180 degrees, finding one that does not measure up, and concluding that this geometrical figure does not necessarily contain that measure.

Conclusion

What is the relevance of the present paper? If we wish to address the undoubted problem of unemployment in many countries, especially that of unskilled young men, it is difficult to see any greater relevance than an analysis of the minimum wage law. Yes, there are other causal factors involved in this scourge: drug addiction, alcohol consumption, mental illness, crime, and incarceration. However, if all of these were solved, arguendo, but the law stipulated a wage below which it was illegal to pay, unemployment for this sector of the economy would still endure.

Which further steps, recommendations, or suggested actions based on the conclusions drawn from this paper can be taken? It is simple. Do not raise the minimum wage level. Do not leave it intact. Do not, even, lower it. Instead, eliminate it entirely. But even that is not fully sufficient. In addition, pass a constitutional amendment that would make it illegal for this law to ever be enacted again.

If the present paper makes such a course of action even slightly more likely than otherwise would have prevailed, it will have made an important contribution toward increasing prosperity in general, reducing misery, and even, possibly, saving lives, since unemployment has far more than merely narrow economic implications.

References

[1] The authors thank Austin Young for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper. We are also grateful to a referee of this journal for assisting us in better organizing the present paper. All remaining errors and infelicities are, of course, our own responsibility.

[2] See on this: D. Neumark, P. Shirley, Myth or measurement: What does the new minimum wage research say about minimum wages and job loss in the United States, Working Paper 28388, NBER 2022; E. Hurst, et al., The Distributional Impact of the Minimum Wage in the Short and Long Run, Working Paper 30294, NBER 2022; J. Lingenfelter, et al., Closing the Gap: Why Minimum Wage Laws Disproportionately Harm African-Americans, “Economics, Management, and Financial Markets”, 2017, 12 (1), pp. 11–24; S.H. Hanke, Let the Data Speak: The Truth Behind Minimum Wage Laws, Cato Institute 2014, https://www.cato.org/commentary/let-data-speak-truth-behind-minimum-wage-laws, (access 12.09.2023); R. Batemarco, C. Seltzer, W.E. Block, The Irony of the Minimum Wage Law: Limiting Choices Versus Expanding Choices, “Journal of Peace, Prosperity & Freedom”, 2014, Vol. 3, pp. 69–83; C. Hovenga, D. Naik, W.E. Block, The Detrimental Side Effects of Minimum Wage Laws, “Business and Society Review”, 2013, Vol. 118, Issue 4, pp. 463–487; P. Cappelli, W.E. Block, Debate over the minimum wage law, “Economics, Management, and Financial Markets”, 2012, 7 (4), pp. 11–33; H. Hazlitt, Economics in One Lesson, Ludwig von Mises Institute 2008; V. Vuk, Professor Stiglitz and the Minimum Wage, Mises Institute 2006, https://mises.org/mises-daily/professor-stiglitz-and-minimum-wage, (access 12.09.2023); W.E. Block, The Minimum Wage: A Reply to Card and Krueger, “Journal of The Tennessee Economics Association”, 2001, https://www.walterblock.com/wp-content/uploads/publications/block_minimum-wage-once-again_2001.pdf, (access 12.09.2023); P. McCormick, W.E. Block, The Minimum Wage: Does it Really Help Workers, “Southern Connecticut State University Business Journal”, 2000, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 77–80; D. Neumark, W. Wascher, Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania: Comment, “American Economic Review”, 2000, Vol. 90, No. 5, pp. 1362–1396; M.N. Rothbard, Outlawing Jobs, 2000, https://www.lewrockwell.com/1970/01/murray-n-rothbard/outlawing-jobs-2/, (access 12.09.2023); D. Hamermesh, F. Welch, Review Symposium: Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage, “Industrial and Labor Relations Review”, 1995, Vol. 48, Issue 4, pp. 827–849; D. Neumark, W. Wascher, Minimum wage effects on employment and school enrollment, “Journal of Business Economics and Statistics”, 1995, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 199–206; D. Neumark, W. Wascher, The Effect of New Jersey’s Minimum Wage Increase on Fast-Food Employment: A Re-Evaluation Using Payroll Records, Working Paper 5224, NBER 1995; T. Sowell, Repealing the Law of Gravity, Forbes 1995, May 22; D. Deere, K. Murphy, F. Welch, Employment and the 1990-91 Minimum-Wage Hike, “American Economic Review”, 1995, Vol. 85, No. 2, pp. 232–237; G.S. Becker, It’s Simple: Hike The Minimum Wage, And You Put People Out Of Work, Bloomberg 1995, http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/stories/1995-03-05/its-simple-hike-the-minimum-wage-and-you-put-people-out-of-work, (access 12.09.2023); D. Neumark, W. Wascher, Employment Effects of Minimum and Subminimum Wages: Panel Data on State Minimum Wage Laws, “Industrial and Labor Relations Review”, 1992, Vol. 46, No.1, pp. 55–81; W.E. Williams, The State Against Blacks, New Press 1982; K.B. Leffler, Minimum Wages, Welfare, and Wealth Transfers to the Poor, “The Journal of Law & Economics”, 1978, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 345–358; J. Mincer, Unemployment effects of minimum wages, “Journal of Political Economy”, 1976, Vol. 84, No. 4, pp. 87–104; M. Friedman, A minimum-wage law is, in reality, a law that makes it illegal for an employer to hire a person with limited skills, http://izquotes.com/quote/306121, (access 12.09.2023).

[3] We are almost embarrassed, but not quite, to depict this simple yet elegant demonstration of the shortcomings of this law. See Figure 1.

[4] Presumably, you will not have to ask for a raise. It will be in the interest of your employer to offer it to you, lest he lose you to another employer, possibly a competitor.

[5] In actual point of fact, the impetus for them flowed from labor unions. We can see this by asking the basic economic question, quo bono? Who benefits? Which persons and/or organization benefit from the unemployment of unskilled workers. The answer is organized labor. Whenever they demand a wage increase, the first thing the employer looks to do is to substitute this factor of production with another one, a cheaper one. Often, two or three less skilled employees can do the same job as one more productive union member. But that is the last thing that would be welcomed by such organizations. How to preclude the competition of such workers? Why, price them out of the market with a minimum wage law!

[6] B. Gitis, How Minimum Wage Increased Unemployment and Reduced Job Creation in 2013, https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/how-minimum-wage-increased-unemployment-and-reduced-job-creation-in-2013/, (access 12.09.2023).

[7] Before the advent of this legislation in the late 1930s in the US, the unemployment rate of whites and blacks, young and middle-aged, was similar. In modern times, the unemployment rate of blacks is double that of whites; teens are unemployed at double the rate of middle-aged individuals. Black teens are jobless at quadruple the rate of whites in their middle ages. See footnote 2, supra.

[8] R.V. Burkhauser, D. McNichols, J.J. Sabia, Minimum Wages and Poverty: New Evidence from Dynamic Difference-in-Differences Estimates, Working Papers 31182, NBER 2023.

[9] For example, members of organized labor.

[10] T. Backhaus, K.-U. Müller, Can a federal minimum wage alleviate poverty and income inequality? Ex-post and simulation evidence from Germany, “Journal of European Social Policy”, 2023, Vol. 33, Issue 2, pp. 216–232, DOI: 10.1177/09589287221144233.

[11] D.W. Schanzenbach, J.A. Turner, S. Turner, Raising State Minimum Wages, Lowering Community College Enrollment, Working Paper 31540, NBER 2023.

[12] This is pretty much a will-o’-the-wisp in any case. Yes, wages can indeed rise following the introduction of, or an increase in, the level mandated by law. However, this is only a temporary effect and lasts only as long as the market can fully react to it. Perhaps the best case ever for legislation of this sort was when the minimum wage was raised from $0.25 to $0.40 per hour. At that time, all elevators were manually operated. It took many months to install automatic elevators, and during that time, the operators did indeed experience a boost in their salaries. But eventually, of course, they were all let go as this technology, which was competitive with workers at the higher salary, replaced them.

[13] J. Meer, H. Tajali, Effects of the Minimum Wage on Non-profit growth, “Oxford Economic Papers”, 2023, Vol. 75, Issue 4, pp. 1012–1032.

[14] According to Assar Lindbeck, in many cases, rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city except for bombing. See: A. Lindbeck, The Political Economy of the New Left, Harper and Row 1972, p. 39. In the view of Gunnar Myrdal: “Rent control has in certain western countries constituted, maybe, the worst example of poor planning by governments lacking courage and vision.” See: G. Myrdal, Opening Address to the Council of International Building Research in Copenhagen, “Dagens Nyheter”, 1965, p. 12; cited in: S. Rydenfelt, The Rise, Fall and Revival of Swedish Rent Control, in: Rent Control: Myths and Realities, eds. W. Block, E. Olsen, The Fraser Insisute 1981, p. 224. For more in this vein, see: V. Perrie, W.E. Block, Rent Control and Public Housing, “Political Dialogues”, 2018, No. 4, pp. 49–56, DOI: 10.12775/DP.2018.004; G. Galles, Rent Control Makes for Good Politics and Bad Economics, Mises Institute 2017, https://mises.org/blog/rent-control-makes-good-politics-and-bad-economics, (access 13.12.2024); W.E. Block, A critique of the legal and philosophical case for rent control, “Journal of Business Ethics”, 2002, Vol. 40, pp. 75–90; W.E. Block, J. Horton, E. Shorter, Rent Control: An Economic Abomination, “International Journal of Value Based Management”, 1998, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 253–263; W. Tucker, The Excluded Americans: Homelessness and Housing Policies, Regnery Gateway 1990; R.W. Grant, Rent Control and the War Against the Poor, Quandary House 1989; J.M. Bruce, ed., Resolving the Housing Crisis: Government Policy, Decontrol, and the Public Interest, The Pacific Institute 1982; W.E. Block, E. Olsen, eds., Rent Control: Myths and Realities, The Fraser Institute 1981; F.A. Hayek, The Repercussions of Rent Restrictions, in: Rent Control: Myths and Realities, eds. W.E. Block, E. Olsen, The Fraser Institute 1981, pp. 169–186; M. Friedman, G. Stigler, Roofs or Ceilings? The Current Housing Problem, in: Rent Control: Myths and Realities, eds. W.E. Block, E. Olsen, The Fraser Institute 1981, pp. 85–103; P.D. Salins, The Ecology of Housing Destruction: Economic Effects of Public Intervention in the Housing Market, New York University Press 1980; Ch. Baird, Rent Control: The Perennial Folly, The Cato Institute 1980; W.S. Grampp, Some Effects of Rent Control, “Southern Economic Journal”, 1950, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 425–447.

[15] C. Fuller, Minimum Wage, Maximum Discrimination, Mises Institute 2021, https://mises.org/mises-wire/minimum-wage-maximum-discrimination, (access 13.12.2024).

[16] G. Galles, Cognitive Dissonance on Minimum Wages and Maximum Rents, Mises Institute 2014, https://mises.org/library/cognitive-dissonance-minimum-wages-and-maximum-rents, (access 12.09.2023).

[17] S.H. Hanke, Let the Data Speak…, op. cit.

[18] Ibidem.

[19] E. Hurst, et al., The Distributional Impact…, op. cit.

[20] Only on a temporary basis until the market adjusts, as we have seen.

[21] On the part of economic illiterates.

[22] R. Nozick, Anarchy, State and Utopia, Basic Books 1977, p. 163.

[23] Raising the Minimum Wage Has Not Led to Higher Unemployment: Evidence from California, An Economic Sense 2024, https://aneconomicsense.org/2024/07/03/raising-the-minimum-wage-has-not-led-to-higher-unemployment-evidence-from-california/, (access 13.12.2024). For support of this side of the debate, see: I.E. Marinescu, Results apply to the fast-food sector and other highly concentrated labor markets, 2023, https://sp2.upenn.edu/study-increasing-minimum-wage-has-positive-effects-on-employment-in-fast-food-sector-and-other-highly-concentrated-labor-markets/, (access 13.12.2024); M. Bennett, The Fight for $20 and a Union: Another California Minimum Wage Earthquake?, LAWCHA 2022, https://lawcha.org/2022/02/19/the-fight-for-20-and-a-union-another-california-minimum-wage-earthquake/, (access 13.12.2024); M. Reich, An $18 Minimum Wage for California, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, University of California 2022. For opponents of this Golden State wage initiative, see: H. Snarr, The Consequences of California’s New Minimum Wage Law, Mises Institute 2024, https://mises.org/mises-wire/consequences-californias-new-minimum-wage-law, (access 13.12.2024); D.W. MacKenzie, California’s Minimum Wage Increase is Inefficient and Unfair, Mises Institute 2024, https://mises.org/power-market/californias-minimum-wage-increase-inefficient-and-unfair, (access 13.12.2024); L. Ohanian, California Loses Nearly 10,000 Fast-Food Jobs After $20 Minimum Wage Signed Last Fall, Hoover Institution 2024, https://www.hoover.org/research/california-loses-nearly-10000-fast-food-jobs-after-20-minimum-wage-signed-last-fall, (access 13.12.2024); S. Drylie, M. Brown, Minimum Wage Laws Can’t Repeal the Laws of Economics, Mises Institute 2024, https://mises.org/mises-wire/minimum-wage-laws-cant-repeal-laws-economics, (access 13.12.2024); E. Boehm, Of Course Special Interests Shaped California’s New Minimum Wage Law, reason 2024, https://reason.com/2024/03/01/of-course-special-interests-shaped-californias-new-minimum-wage-law/, (access 13.12.2024); B. Seevers, California’s Crony Capitalist Minimum Wage Law, Mises Institute 2024, https://mises.org/mises-wire/californias-crony-capitalist-minimum-wage-law, (access 13.12.2024).