Rebaz Jalal Ahmed Nanekeli

Full Article: View PDF

How to cite

Nanekeli R.J.A., World Powers and the Fate of the Iraqi Kurds: Geopolitical Instability, the Emergence of the Kurdistan Region in Iraq, and Its Survival, “Polish Journal of Political Science”, 2024, Vol. 10, Issue 2 (Special Issue), pp. 127–147, DOI: 10.58183/pjps.0502SI2024.

ABSTRACT

The article examines the influence of global powers on the situation of the Kurds in Iraq from the end of World War I to the present. Given the limited research on this subject, the paper evaluates the hypothesis that superpowers have played a decisive role in shaping the status of the Kurdish people. Employing the author’s methodology, which is based on the Index of Geopolitical Relations Stability (IGRS), the study traces the evolution of international politics – from British-French domination through the Cold War era to the period of American hegemony. The analysis highlights significant historical events and investigates the impact of global powers on the policies of regional states (Iran, Turkey, Syria, and Iraq) concerning the Kurdish question. The findings confirm the pivotal role of superpowers in determining the extent of Kurdish autonomy and underscore the critical importance of economic factors, particularly control over oil fields. This study offers valuable insights into the mechanisms shaping the international position of non-state actors within a system dominated by global powers.

Keywords: world powers, Kurds, Iraqi Kurdistan, Middle East, regional powers, geopolitics

Introduction

The 20th century brought profound changes to the geopolitical order, establishing a system grounded in international law and the concept of nation-states. This new framework, shaped by treaties and international organizations, significantly raised the threshold for accepting unilateral territorial changes. The League of Nations, and later the United Nations, established a legal framework requiring broad international consensus, particularly among world powers, for any changes to national borders. Efforts to impose unilateral territorial changes often resulted in severe international conflicts. Within this system, nations that failed to establish their own states at critical historical junctures found themselves in enduring political and economic dependence on world powers. This dynamic is especially apparent in the case of the Kurdish people.

The Middle East serves as a prime example of a region whose modern configuration was shaped by the interests of superpowers during the early 20th century. While the division of territories following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire has been extensively examined in the literature, the Kurdish question – despite its critical importance to regional stability – has not received proportional attention in academic research. This relative marginalization stemmed not only from the political instrumentalization of the Kurdish issue by regional powers and states but also from the broader geopolitical context, where the priority was to preserve the stability of borders established under the mandate system. Economic interests, particularly those tied to the control of oil fields, played a decisive role. Unlike other ethnic groups in the region, such as the Jews with their successful Zionist movement, the Kurds failed to garner significant and sustained international support for their national aspirations. It was not until the late 20th century – marked by events such as the March Uprising of 1991 and the establishment of the autonomous Kurdistan Region – that research interest in this issue grown significantly, paving the way for more in-depth analysis of the powers’ roles in shaping the plight of the Kurdish people.

The division of the Middle East began even before the end of World War I, when Britain, France, and Tsarist Russia engaged in secret negotiations over future spheres of influence. The 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, despite Russia’s subsequent withdrawal following the Bolshevik Revolution, became the foundation for the later arrangements formalized at the San Remo conference in 1920, which ultimately defined the post-war regional order. These British-French agreements resulted in the creation of several new states, often disregarding local ethnic and historical realities. Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Transjordan, and Palestine emerged as newly delineated entities, while Turkey’s borders were redefined. Amid this process, the fate of the Kurdish people was particularly dire. Although the Treaty of Sèvres (1920) included provisions for the possible establishment of a Kurdish state, these provisions were never implemented due to opposition from the Turkish nationalist movement. The subsequent Treaty of Lausanne (1923) entirely omitted the Kurdish question. Despite some international support, including efforts by the United States to advocate for the rights of ethnic minorities in the region, the Kurds were denied the right to self-determination. These decisions, driven by the geopolitical and economic interests of the superpowers, entrenched the division of the Kurdish nation among four states – a situation that has persisted for decades.

The contemporary geopolitical landscape of the Middle East has shifted considerably from the order established after World War I. While the United States remains a central player in the region, emerging Asian powers, particularly China, are increasing their economic engagement in the Middle East. Chinese investments in energy infrastructure, along with the presence of other Asian economic partners, are introducing new dynamics to the regional balance of power. For the Kurdistan Region, these developments hold the potential for diversifying international economic and energy partnerships. However, internal political divisions within Iraqi Kurdistan, especially the rivalry between the main Kurdish parties, coupled with the strong influence of traditional regional actors, significantly constrain the region’s capacity to capitalize on these evolving international dynamics.

This study focuses on the situation of the Iraqi Kurds, with particular emphasis on the emergence and development of the Kurdistan Region as an autonomous political entity in northern Iraq. The analysis covers key events, from the unilateral declaration of independence in 1919, through the March uprising of 1991 leading to the establishment of the Kurdistan Government in 1992 and its recognition as legitimate in the Iraqi Constitution of 2005, to the independence referendum in 2017. The purpose of the study is to demonstrate the determining role of world powers, especially the United States, in shaping the situation of the Iraqi Kurds and in the process of the emergence and development of the Kurdistan Region.

Methodological Approach

The paper attempts to analyze the situation of the Iraqi Kurds from the First World War to the present day, focusing on the policies of the world powers (Britain and France) and their influence on the newly established regional states (Turkey and Iran). Special attention is given to the role of the world powers in shaping the situation of the Kurds and in the process of establishing the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The geopolitical relations of the regional states toward Iraqi Kurdistan are also examined. The analysis is arranged chronologically, according to the most significant historical events.

The primary research method involved analyzing the relevant literature. The literature review examined the situation of Iraqi Kurdistan from the perspective of historical, geopolitical, and economic conditions, placing special emphasis on the region’s oil resources. The analysis was conducted in chronological order, covering the period from the establishment of the Iraqi state to the present day, taking into account the key historical event of the annexation of the Mosul wilayat to the newly formed Iraq. The analysis is based on historical documents relating to the partition of the Middle East and the formation of the Iraqi state, including the Sykes-Picot Agreement, the resolutions of the San Remo conference (1920), the Treaties of Sèvres and Lausanne (1923), the 1925 report of the League of Nations Commission on the Mosul wilayat, and the 2005 Iraqi Constitution. A rich body of literature on the subject was utilized, including both classic studies on the history of the Kurds and Iraq (McDowall, Tripp, Anderson, and Stansfield) and more recent publications on the contemporary geopolitical situation in the region (Phillips, Sosnowski). Sources also included historical documents and press reports on recent events (Rudaw.net, The Economist).

The study hypothesizes a significant influence of world powers on the geopolitical situation of Iraqi Kurdistan. It assumes that the positions and decisions of the world powers significantly affect both the situation of the Kurds directly and indirectly by shaping the policies of regional states. According to this hypothesis, the actions of the regional states toward Iraqi Kurdistan are largely determined by the broader geopolitical context and the interests of the world powers, although these states retain a degree of autonomy in their decisions. As a result, the current status of Iraqi Kurdistan is a consequence of the complex interaction between the policies of world powers and the responses of regional states, with the shifting priorities and interests of the major global powers playing a crucial role over time.

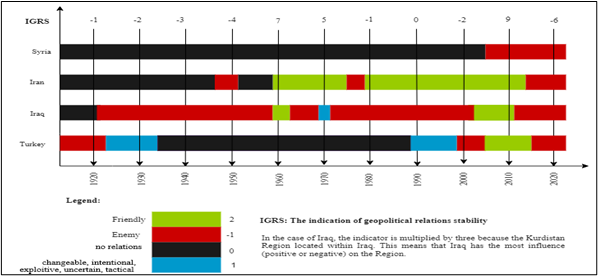

To verify the hypothesis, an analysis of the situation of the Iraqi Kurds over the past century was conducted, identifying key historical events and their impact on the position of this community. Particular attention was given to examining how the positions of world powers influenced the decisions of regional states. To more accurately depict these relationships, a system for visualizing geopolitical relations was developed, using numerical values to describe the two main dimensions of the analysis: the attitudes of world powers toward Iraqi Kurdistan and the attitudes of regional states toward Iraqi Kurdistan within the context of superpower politics. The system takes into account three levels of influence: (1) the home state (Iraq); (2) the regional states surrounding Iraqi Kurdistan; and (3) the world powers.

The system of indicators used was designed to verify the main research hypothesis: the significant influence of world powers on the geopolitical situation of Iraqi Kurdistan. The indicator values (ranging from -1 to 2) allow for the quantification and comparison of changes in international relations at two key levels of analysis.

At the level of relations with world powers, the indicators allow for tracking changes in the attitudes of major international actors toward the Kurdish issue. A positive value (1 or 2) indicates active involvement of the powers in shaping the situation of Kurdistan, while a zero or negative value suggests the absence of such involvement or actions counter to Kurdish interests. At the level of regional relations, the system of indicators enables the verification of the second part of the hypothesis, concerning the indirect influence of the superpowers by shaping the policies of the regional states. The synchronization of changes in the values of the indicators across both levels (international and regional) over the decades may reveal a relationship between the policies of the superpowers and the actions of regional states toward Kurdistan.

The proposed system for quantifying geopolitical relations uses a scale from -1 to 2, where the individual values reflect the nature of the political relationship, as follows:

- value 2 (green): indicates a friendly relationship, characterized by sustained political, economic, or military support and stable cooperation;

- value 1 (blue): indicates a volatile, tactical, or uncertain relationship, driven by ad hoc political or strategic interests, often subject to rapid change in response to new circumstances;

- value 0 (black): indicates a nonexistent political relationship, indicating neutrality, disregard, or no direct influence on the region;

- value -1 (red): indicates an unfriendly relationship, characterized by hostile political, economic, or military actions aimed at undermining the position of Iraqi Kurdistan.

A scale of -1 to 2 was chosen as the simplest possible representation of the main types of international relations, where a negative value indicates hostility and positive values reflect varying degrees of cooperation. A value of 2 represents a “friendly relationship,” denoting active political, military, or economic support. A value of -1 represents a “hostile relationship,” characterized by efforts to undermine the political representation of the Iraqi Kurds. A value of 1 reflects a “volatile relationship,” where short-term cooperation with the political representation of the Iraqi Kurds occurs, but without long-term commitment.

Due to the special role of Iraq as the home state for Iraqi Kurdistan, the values for that country are multiplied by 3 to properly reflect the intensity of the central power’s influence on the autonomous region. The use of the multiplier (x3) for the indicators relating to Iraq underscores the unique role of this country in the verification of the hypothesis, enabling an assessment of the extent to which the home state’s policy toward Kurdistan was shaped by the position of world powers.

The graphical analysis is divided into two factor groups: world powers and regional states. The graphical representation of the results in the form of charts facilitates the identification of periods during which the influence of the superpowers was particularly significant, as well as those in which regional or domestic factors predominated.

It should be emphasized that the assigned numerical values are subjective in nature and were determined based on a general historical analysis of the behavior and attitudes of both world powers and regional states (Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria) toward Iraqi Kurdistan. The main limitation is the subjective nature of coding and the simplification of complex international relations to single numerical values. The model also does not account for internal divisions within individual states or the political organization of Iraqi Kurds.

Periodization was used in the graphical representation of the results. Decades were chosen as natural units of analysis to capture long-term trends in international relations. For events at the turn of the decades, their most important direct effects were considered and attributed to the period in which they were most prominent. Within each decade, the dominant nature of relations was analyzed, taking into account the importance of individual events to the overall political situation of the Iraqi Kurds. Particular importance was given to events leading to permanent changes in the status of the region. The methodology adopted allows for an effective depiction of the overall trends in international relations regarding Iraqi Kurdistan. The simplistic nature of the quantitative analysis is balanced by a qualitative analysis of specific historical events.

The Status of the Kurds After the Partition of the Ottoman Empire and the Tactical Behavior of the Great Powers

The division of the Middle East after World War I by Britain and France, as part of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, fundamentally impacted the future of the region. The 1920 San Remo conference, which formally determined the fate not only of the Turks and Arabs but also of the Kurds, marked a pivotal moment in the process of shaping a new geopolitical order.[1] The issue of control over oil fields played a pivotal role in this process, directly influencing the exclusion of the Kurds from negotiations over their self-determination. This occurred despite Woodrow Wilson’s recognition of their rights to autonomy, as outlined in his peace program presented in his 11 February 1918 address to Congress.[2]

Wilson’s ideas were only partially reflected in the provisions of the 1920 San Remo Conference, which primarily focused on the division of the former Ottoman Empire between France and Britain, while ignoring the aspirations of non-Turkish peoples. These arrangements were followed by the Treaty of Sèvres, which proposed autonomy for the Kurds living in southeastern Anatolia and the possibility of establishing an independent Kurdish state, should such an intention be expressed and accepted by the League of Nations. However, these plans were thwarted by the Turkish national movement led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who rejected the provisions of the Treaty of Sèvres in the wake of its successes in the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923). Consequently, the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne completely disregarded the issues of Kurdish autonomy and statehood, reinforcing the division of Kurdish territories between Turkey, Iraq, and Syria.[3]

Particularly significant in this context was the attitude of British decision-makers. Sir Percy Cox, the High Commissioner in Baghdad, along with the British-appointed King Faisal I of Iraq of the Hashemite dynasty, opposed the creation of a Kurdish state. Even Winston Churchill (then Secretary of State for the Colonies; 1921–1922), who was initially sympathetic to Kurdish independence, ultimately supported the inclusion of the Kurds in the newly-formed Iraq. These actions were part of a broader British strategy to expand its own hegemony, control the oil fields, and limit Turkish influence in the Middle East. The issue of the Mosul wilayat, a key area of dispute between[4] Britain and Turkey due to its location and oil resources, played a crucial role in this process. A League of Nations commission investigating the matter in the first half of 1925 acknowledged the demographic dominance of the Kurds (who made up 5/8 of the population) and their positive relations with the Christian community.[5] Nevertheless, it recommended that the region remain within Iraq’s borders, subject to two conditions: maintaining the League of Nations mandate for 25 years (or until Iraq’s membership in the League) and guaranteeing the protection of the rights of the Kurdish minority.[6]

British policy toward the Kurds was characterized by volatility and pragmatism. The initially favorable attitude toward the pro-British Kurds shifted in response to events in Turkey, particularly after its victory over Greece in 1922.[7] Both British and Turkish actions against the Kurds were purely tactical, driven by the pursuit of their own strategic interests.[8] In 1925, the situation became more complicated when a British oil company was granted a concession to extract oil in Iraq.[9] Kurdistan was transformed into a strategic and defensive territory, controlled by British political officers working with local tribal leaders.[10] A British-Iraqi agreement, which guaranteed Britain 25 years of consultative powers over Iraq’s foreign policy, ultimately sealed the fate of the Kurds.[11]

It should be pointed out that Britain bore responsibility for the fate of the Kurds in the creation of Iraq, as it failed to provide them with legal and institutional protection. Despite the League of Nations’ recognition of Iraq as a sovereign state in 1932, Britain retained considerable political, economic, and military influence through a 1930 treaty that allowed the stationing of troops, control over Iraq’s foreign policy, and dominance over its oil resources. The British attitude, initially more sympathetic to Kurdish aspirations, shifted as Iraq’s stability became increasingly important to British oil interests. The consequence of this shift was the suppression of Kurdish uprisings – first by Sheikh Ahmed Barzani in 1931-1932 and later by his brother Mustafa in 1943.

Developments Regarding the Kurds After the 1958 Coup in Iraq

A turning point in Iraq’s history came with the 1958 coup that overthrew the Hashemite monarchy. The new leader, General Abd al-Karim Qasim, introduced radical changes in both the country’s domestic and international politics. Iraq’s growing rapprochement with the Soviet Union raised concerns among Western powers, particularly Britain and the United States. Initially, Qasim adopted a conciliatory policy towards the Kurds, recognizing them as “one of Iraq’s two major nations” and promising greater autonomy.[12]

However, this period of relative stability lasted only three years.[13] In 1961, after negotiations with the central government failed, Kurdish forces, led by Mustafa Barzani, launched an armed insurgency. With the support of Iran and the use of guerrilla tactics, the Kurds managed to seize control of a large area of northern Iraq (approximately 25,000 square miles), establishing de facto sovereign control over the territory. Successive nationalist governments, including the regimes of the Arif brothers and Saddam Hussein, were unable to reach an agreement with the Kurds. The Iraqi-Kurdish conflict continued unabated until 1970, claiming an estimated 100,000 lives.[14]

During the conflict, the Kurds received substantial support from various states pursuing their own strategic interests.[15] The USSR backed the Kurds from 1961 to 1972 as a means of exerting pressure on Iraq within the broader context of its rivalry with the United States. Iran provided military aid from 1966 to 1975 in an effort to destabilize Iraq by fueling internal conflicts. The U.S. offered support to the Kurds between 1972 and 1975 as part of its Cold War rivalry with the Soviet Union, while Israel, during the same period, sought to divert Iraqi forces from the Arab-Israeli conflict.[16]

In 1970, Mustafa Barzani signed the so-called March Manifesto, a twelve-point agreement between the Iraqi government and Kurdish forces that promised autonomy. However, the document proved to be little more than Baghdad’s tactical maneuver and was never implemented.[17] The situation changed dramatically in 1972 when Iraq signed a friendship pact with the USSR and nationalized its oil industry. Previously a mediator and supporter of the Kurdish cause, the USSR withdrew its backing after the Baghdad Pact was signed.[18] These developments raised concerns not only in Iran and Israel but also in the U.S..

In 1975, rather than seeking an agreement with the Kurds, the Ba’athist government accepted an Iranian proposal, offering territorial concessions on the shared border in the Shatt al-Arab region in exchange for the withdrawal of Iranian support for the Kurds. The Algiers Agreement[19] led to a complete cessation of international aid to the Kurds,[20] effectively ending their 14-year struggle for autonomy.

The outbreak of the Iraq-Iran War in 1980, triggered by Iraq’s attack on Iran, marked the beginning of a new and tragic chapter. Both sides in the conflict exploited the Kurdish minority to further their own military and political objectives.[21] Western countries, led by the United States, supported Iraq against Iran, providing agricultural loans and sharing intelligence. Arab countries also sided with Saddam Hussein. During this period, the international community largely ignored the internal situation in Iraq, including the Anfal (Arabic for “the spoils of war”) campaign of the 1980s, in which the regime systematically sought to annihilate the Kurdish population, using chemical weapons against civilians.[22]

It was not until August 1988, at Britain’s request, that the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 620, condemning the use of weapons of mass destruction during the Iraq-Iran war.[23] However, the resolution had only symbolic significance. The U.S. administration exercised restraint over the chemical attack on Halabja, continuing to provide military and financial aid to Iraq in support of its conflict with Iran.

The period from the 1958 coup to the late 1980s clearly illustrates how the shifting geopolitical interests of world powers shaped the situation of the Kurds in Iraq. International support for Kurdish autonomy never stemmed from a genuine concern for their self-determination but was rather a tool in the global political game. Both the USSR and the U.S. viewed the Kurdish issue as part of a broader regional strategy, as evidenced by their changing positions following the signing of the Iraq-Soviet Friendship Agreement in 1972. This reinforces the idea that the strategic interests of the superpowers in the Iraq-Iran conflict took precedence over the protection of human rights during the genocidal Anfal campaign. These events highlight the decisive role of world powers’ policies in shaping not only the immediate situation of the Kurds but also in influencing the attitudes of regional states toward Kurdish independence aspirations.

The March Uprising and the Formation of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

The March Uprising of 1991 marked a watershed moment in the history of the Kurdish people. Following Iraq’s defeat in the war for Kuwait, the Kurdish rebellion against Saddam Hussein’s regime ended in brutal crackdown and a mass exodus of the Kurdish population to Iran and Turkey.[24] The humanitarian crisis on the borders prompted the international community to intervene.

In response to an appeal by Turkey and Iran, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 688, the first international document directly addressing the Kurdish question since the Treaty of Sèvres (1920). France played a key role in mobilizing the international community, influencing a change in the U.S. position[25] and the formation of a coalition of Western countries to protect the Kurds.[26]

The U.S.-British-French-Turkish coalition initiated Operation Provide Comfort, establishing a safe haven north of the 36th parallel. This action not only enabled the return of refugees but also created the conditions for the establishment of de facto Kurdish autonomy in northern Iraq.[27] Resolution 688 was of fundamental importance to the Iraqi Kurds, providing them with the first international protection from repression by the home state in modern history and laying the groundwork for the establishment of their own administrative structures.

The Overthrow of the Regime in Baghdad vs. the Legitimization of the Kurdistan Region

The 2003 invasion of Iraq marked the beginning of a new phase in the Kurdistan Region’s relations with Iraq, Iran, Turkey, the United States, and Western countries. Initially, U.S. policy was characterized by an ambivalent attitude toward Kurdish demands, but it evolved under the influence of the need to win Kurdish support for U.S. objectives in the region.[28]

The Kurdish armed forces, consisting of 75,000 Peshmerga, were the only pro-coalition group in Iraq. However, the first phase of U.S. policy focused primarily on supporting the Iraqi government, a strategy that ultimately hindered U.S. interests in the region.[29] The breakthrough came in 2005 when the Kurds formed the second-largest bloc in the Iraqi parliament, leading to a shift in the U.S. position. A key event was the adoption of Iraq’s new constitution, which formally recognized the Kurdistan Region as a federal entity.

However, the implementation of the constitutional provisions faced resistance from the central authorities. The status of disputed areas, particularly the oil-rich city of Kirkuk, remained unresolved, and a law to regulate oil and natural gas production was never passed. Baghdad, aiming to weaken the Kurdistan Region, utilized economic tools as a form of political pressure. This culminated in 2014 with the withholding of constitutionally guaranteed budget transfers to Iraqi Kurdistan.

The evolution of U.S. policy – moving from initial distance from Kurdish aspirations to a pragmatic partnership, and ultimately supporting the region’s federal status – has directly impacted Kurdistan’s position in post-war Iraq. At the same time, the challenges surrounding the implementation of the 2005 constitution highlight the limitations of the superpowers’ external influence. Despite American backing for Kurdish autonomy, the authorities in Baghdad effectively obstructed the implementation of key provisions. This situation underscores the complex dynamics between the policies of world powers and the reactions of regional states, where formal international guarantees do not always result in tangible changes to the political status of the Kurds.

Independence Referendum vs. Behavior of Powers

The 2014 conflict with the Islamic State, which seized a third of Iraq’s territory, created a new dynamic in Kurdish-Iraqi relations. Faced with the threat, Kurdish authorities took control of strategic, oil-rich Kirkuk and other disputed areas. This action, although justified by the need to defend against ISIS, was interpreted by Iraq, Iran, and Turkey as a campaign for secession.

Despite their commitment to fighting the Islamic State, Kurdish authorities decided to hold an independence referendum. On 25 September 2017, 92.7% of voters supported independence.[30] Baghdad’s initially hesitant response hardened after the international community endorsed Iraq’s territorial integrity. With the support of Iranian artillery, Iraqi forces took control of Kirkuk and the disputed areas. The Peshmerga, keen to avoid significant losses, withdrew without a fight. The only major confrontation occurred near the town of Pirde (Altun Kupri), near Erbil, where, according to the Kurdish Regional Government, 30 Peshmerga were killed, and Iraqi forces suffered casualties in personnel and equipment, including the loss of an M1 Abrams tank.[31]

Baghdad declared the referendum illegal, demanding within 72 hours that control of border crossings and oil revenues be handed over.[32] Iran closed its borders with the Kurdistan Region, while Turkey kept its border crossings open due to oil deals[33] and the significant volume of trade with Iraq through Kurdish territory.

France played a key role in deescalating the conflict. A month and a half after the referendum, President Macron received a Kurdish delegation led by Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani at the Élysée Palace. French mediation, which called for dialogue within the framework of the Iraqi constitution, contributed to the initiation of negotiations between Erbil and Baghdad and helped develop a new model of cooperation.[34]

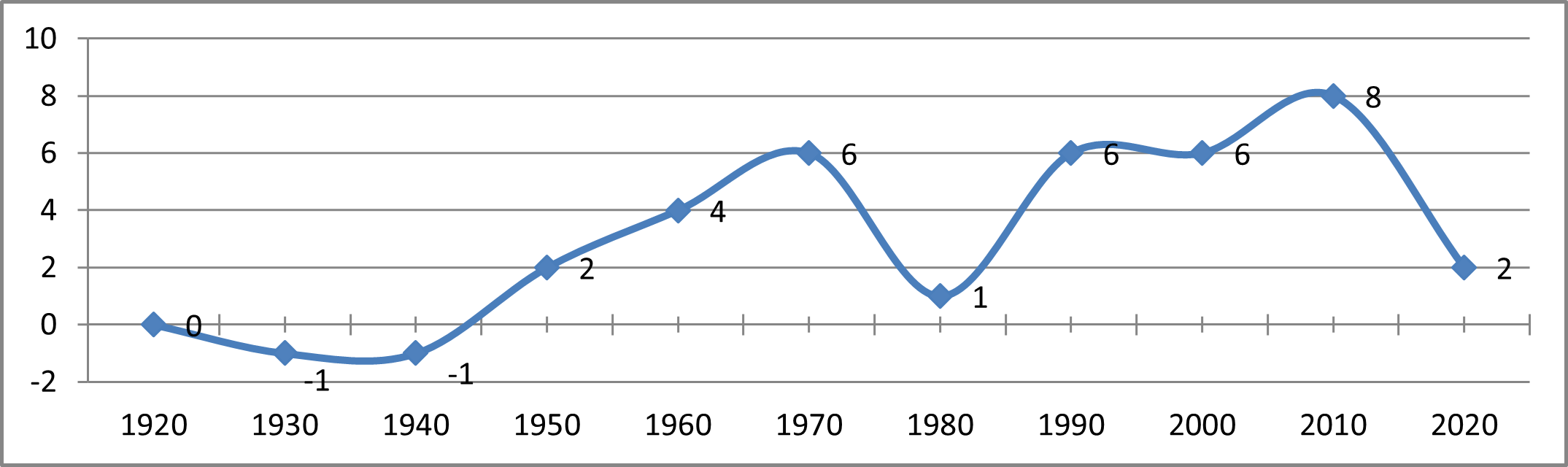

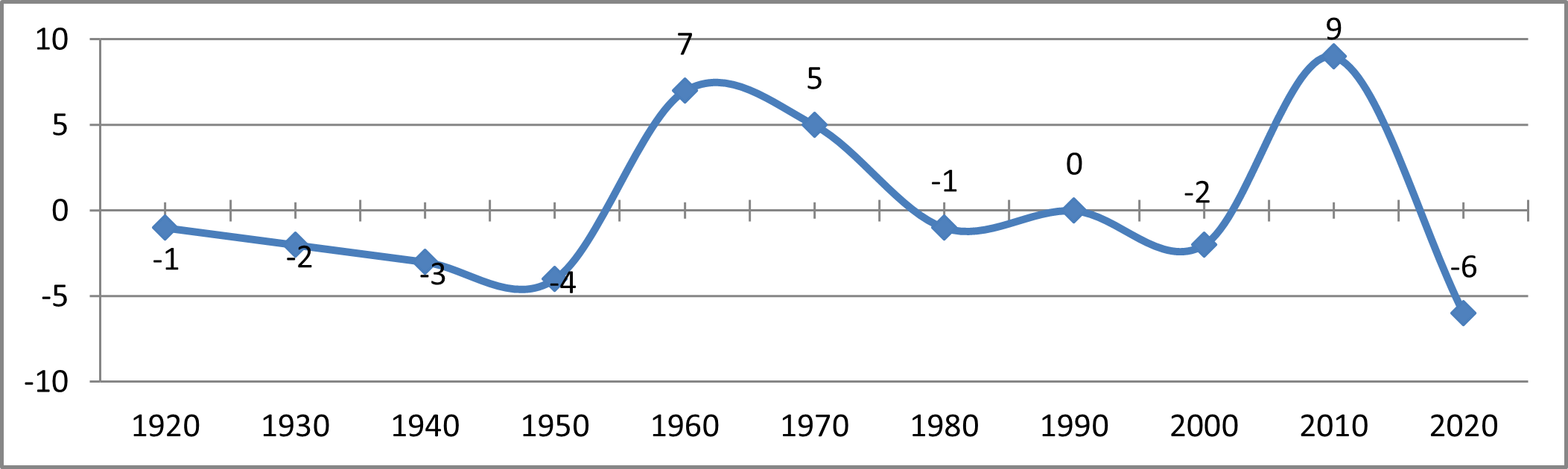

In order to systematically analyze international influences on the situation of Iraqi Kurdistan, a system of indicators was developed to illustrate the historical development of the region’s relations with both regional states (Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria) and world powers (Britain, France, Russia, the United States, and Israel). The results of the analysis are illustrated through Figures 1 and 2, using the indicators defined in the methodology section.

Figure 1, illustrating the nature of the relationship between world powers and Iraqi Kurdistan, uses a four-level scale of values represented by colors. Black (a value of 0) indicates no relationship, blue (a value of 1) indicates a volatile relationship, dependent on current interests, red (a value of -1) represents hostile relations, and green (a value of 2) indicates friendly relations. The analysis was performed over ten-year periods, which makes it possible to observe long-term trends in international policy toward Iraqi Kurdistan.

Figure 1. Sub-indicators of the geopolitical standing of Iraqi Kurdistan – international perspective

Source: own study (explanations in the text).

Figure 2. Sub-indicators of the geopolitical standing of Iraqi Kurdistan – regional approach

Source: own study (explanations in the text).

Figure 2 illustrates the relations between Iraqi Kurdistan and regional states, using a color system similar to that of world powers. However, this analysis broadens the interpretation of the color blue, which, in addition to indicating a volatile relationship, also reflects its instrumental, tactical, and uncertain nature. Given Iraq’s unique position as the home state relative to the Kurdistan Region, the values for this country were multiplied by a factor of 3 to better capture its dominant influence over the region’s situation.

For both charts, the Index of Geopolitical Relations Stability (IGRS) was calculated by summing the values assigned to each country in each decade. For example, for the year 2020, the sum of the values (-1) + (1) + (-1) + (2) results in an IGRS of 2. Figures 3 and 4 are based on these calculations.

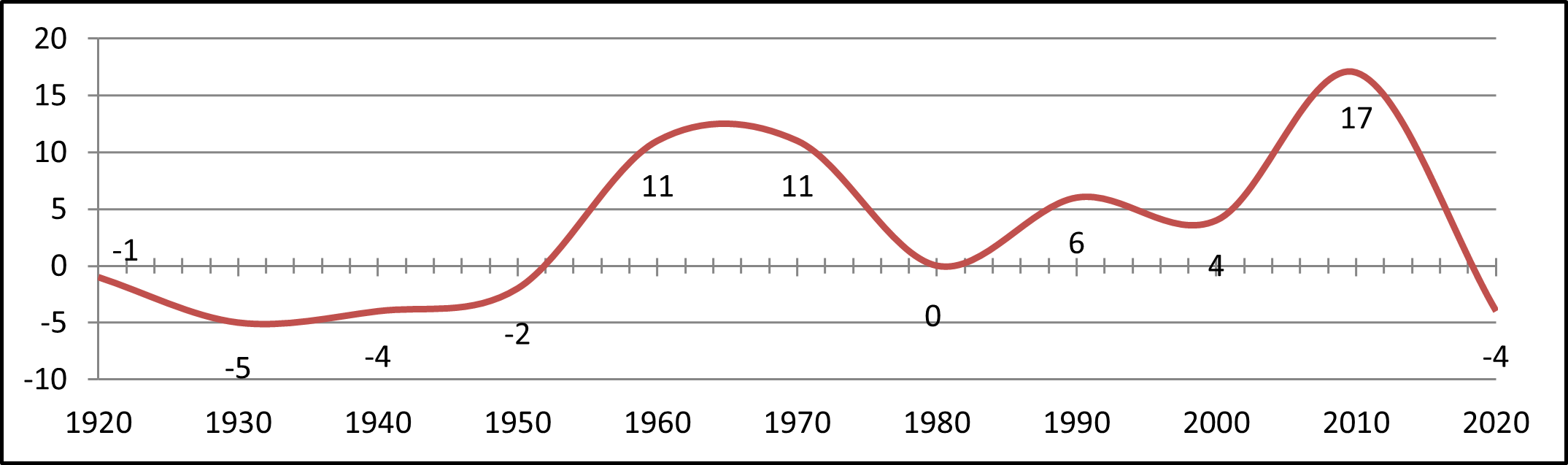

A comparative analysis of Figures 3 and 4 reveals a significant correlation between the policies of world powers and the actions of regional states toward Kurdistan. The convergence of these trends highlights the dominant role of the superpowers in shaping the geopolitical landscape of the region, with neighboring states tending to align their policies with those of the major world powers. This correlation supports the thesis that the policies of the superpowers are crucial in determining the status of the Kurdistan Region.

Figure 3. Synthetic indicator of the geopolitical standing of Iraqi Kurdistan – international perspective

Source: own study.

Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of relations between world powers and the Kurdistan Region. Values below zero represent particularly unfavorable periods for Kurdistan, while positive values indicate an improvement in international relations. A key turning point occurred in 2003 with the emergence of the United States as a major actor in the region, coinciding with the first period of real autonomy for Kurdistan. The U.S. withdrawal in 2014, as part of the Iraq agreement, led to a significant weakening of the Kurdistan Region’s political position, underscoring the decisive influence of relations with Western powers on the region’s stability.

Figure 4, which depicts Kurdistan’s relations with regional states, clearly correlates with the data presented in Figure 3. This convergence demonstrates that the policies of regional states towards Kurdistan were largely shaped by the broader geopolitical context. This is especially evident during the period of dominance by the Entente states, whose military superiority enabled them to influence the regional balance of power. Similarly, the powers responsible for the post-war division of the Middle East continued to exert a decisive influence on the nature of interstate relations in the region.

Figure 4. Synthetic indicator of the geopolitical standing of Iraqi Kurdistan – regional approach

Source: own study.

Figure 5 presents a synthesized list of indicators of Iraqi Kurdistan’s geopolitical position, combining both regional and international perspectives. Analyzing this list reveals three key periods in the region’s history. From 1950 to 1970, the involvement of world powers positively impacted both the Kurdistan Region and Iraq, resulting in relatively favorable policies from neighboring countries.

The years 1975 to 1989 marked the most dramatic period in the history of Iraqi Kurdistan, characterized by the complete withdrawal of international support for the Kurds. Change came only after the U.S. intervention in Iraq in 2003, which marked the beginning of a period of relative stability that lasted until the U.S. withdrawal in 2011.

This analysis confirms the direct correlation between the involvement of world powers and the geopolitical situation of Iraqi Kurdistan, highlighting the crucial role of international support in shaping the Kurds’ regional position.

Figure 5. Combined index of the geopolitical standing of Iraqi Kurdistan – a comparison of regional and international snapshots

Source: own study.

The analysis of the indicators shown in Figures 3-5 reveals the structural instability of the geopolitical position of the Iraqi Kurdistan Region. This instability is evident both in its relations with Iraq, as the home state, and in its interactions with regional states and world powers. Of particular significance was the dominance of geopolitical factors over economic considerations in shaping the region’s situation at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries. Given the region’s ongoing dependence on the political decisions of world powers and regional states, the long-term stability of the Kurdistan Region’s status remains difficult to predict.

Conclusions

The modern geopolitical situation of Iraqi Kurdistan is a direct consequence of the actions taken by world powers after World War I. Britain and France, replacing the Ottoman Empire and establishing a new order through the Sykes-Picot Agreement, became the architects of the modern Middle East, including the borders of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, as well as the new Turkey and Iran. The graphical analysis conducted (Figures 1-5) documents the evolution of the geopolitical situation of Iraqi Kurdistan since the creation of Iraq in 1921, revealing the crucial role of the powers in shaping both internal Iraqi politics and the stance of regional states toward the Kurds.

The fate of the Kurdish community in Iraq was sealed by the League of Nations’ 1925 decision to incorporate the Mosul wilayat into the Iraqi state. From 1921 to 2003, the influence of the superpowers on Iraq’s political situation remained constant, albeit with varying intensity, as demonstrated by the lack of response to the persecution of the Kurds in the 1970s and 1980s. After the overthrow of the Hussein regime in 2003, the United States and the international coalition actively shaped Iraq’s domestic politics, this time including the Kurds as key political actors. The discovery of oil fields in Kurdish areas further strengthened their position, and the Kurdistan Region became a stable area in post-war Iraq.

The crisis surrounding the expansion of the so-called Islamic State initially enhanced the Kurds’ role as a key partner in the fight against terrorism. However, after ISIS was defeated, particularly following the 2017 Kurdish independence referendum, Western powers shifted their support to Iraq’s territorial integrity, leading to the isolation of the Kurds and the loss of control over Kirkuk.

The analysis confirms the hypothesis of an important role of the world powers in shaping the situation of the Iraqi Kurds – ranging from their exclusion from the right to self-determination, to the creation of an autonomous region, and ultimately to the failure of the independence referendum. The future of Iraqi Kurdistan remains uncertain, despite its strategic role as an partner of the West and its significant energy resources. The rise of new economic powers, such as China and India, as well as potential shifts in the global energy system, could have a profound impact on the region. Additionally, internal political divisions among rival Kurdish factions are weakening the region’s negotiating position, both internationally and with Baghdad.

Growing research interest in the Kurdish issue could contribute to a deeper understanding of the complexity of this nation’s situation and potentially shift the international community’s approach to Kurdish national aspirations. Further research into the Kurdish situation is crucial for a more comprehensive understanding of the geopolitical dynamics of the Middle East.

The methodology used in this study, based on the quantification of geopolitical relations, enabled a systematic analysis of the changing position of Iraqi Kurdistan. The IGRS system of indicators effectively highlighted the correlation between the policies of world powers and the actions of regional states. The graphical analysis confirmed that key turning points in the region’s history (1925, 1958, 1991, 2003, 2014, and 2017) coincided with shifts in the policies of world powers.

The study also emphasized the central role of the economic factor, particularly control over oil fields, in shaping the strategies of the superpowers. This can be traced from the decision to incorporate the Mosul wilayat into Iraq in 1925, through the Cold War era, to contemporary international relations. The significance of this factor has steadily increased, as reflected in the IGRS index values in the subsequent decades.

The analysis conducted successfully achieves the research objectives, documenting the evolution of the role of world powers in shaping the situation of the Kurds – from the imperial policies of Britain and France, through the period of U.S.-Soviet rivalry, to the contemporary dominance of U.S. hegemony. The role of the United States after 2003 in the process of institutionalizing Kurdish autonomy was particularly significant, although subsequent developments highlighted the limitations of this support.

The findings point to the need for further research in two key areas: the impact of emerging economic powers, such as China and India, on the region’s future, and the significance of internal political divisions for the stability of Iraqi Kurdistan. These factors could have a profound impact on the region’s future geopolitical position.

References

[1] D.L. Philips, The Kurdish Spring, A new map of the Middle East, Transaction Publishers 2015, pp. 27–30; S. Meiselas, Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History, Random House 1997, pp. 96–107.

[2] C. Frappi, The Energy Factor: Oil and State-Building in Iraqi-Kurdistan, in: Kurdistan an Invisible Nation, ed. S.M. Torelli, The Italian Institute for International Political Studies 2016, pp. 91–121.

[3] H.A. Jamsheer, Współczesna historia Iraku, Wydawnictwo Akademickie DIALOG 2007, pp. 68–69; K. Yildiz, The Kurds in Iraq: The Past, Present and Future, Pluto Press 2004, pp. 10–13.

[4] Q. Wright, The Mosul dispute, “American Journal of Intenational Law”, 1926, Vol. 20, Issue 3, pp. 453–464.

[5] D. McDowall, A modern history of the Kurds, I.B. Tauris Publishers 2000, p. 144; D. McDowall, The Kurds. A Nation Denied, Minority Rights Group 1992, p. 81.

[6] VII. Post-War Liquidation in the Near East, “Political Science Quarterly”, 1926, Vol. 41, Issue 1, p. 122, DOI: 10.2307/2142628.

[7] D.K. Fieldhouse, Kurds, Arabs and Britons. The Memoir of Wallace Lyon in Iraq, I.B. Tauris 2002, p. 45.

[8] M.R. Izady, The Kurds. A Concise Handbook, Taylor & Francis 1992, p. 69.

[9] G. Anaz, Iraq: Oil and Gas Industry in the Twentieth Century, Nottingham University Press 2012, pp. 46–140.

[10] D. Kołodziejczyk, Turcja, Trio 2000, pp. 67–73.

[11] K. Korzeniewski, Irak, Wydawnictwo Akademickie DIALOG 2004, pp. 49–50.

[12] A.R. Ghassemlou, Kurdystan i Kurdowie, transl. E. Danecka, Książka i Wiedza 1969, pp. 266–267.

[13] A.I. Dawisha, Iraq: a political history from independence to occupation, Princeton University Press 2009, pp. 197–198.

[14] J. Ciment, The Kurds. State and minority in Turkey, Iran and Iraq, Facts On File 1996, pp. 58–61.

[15] Muhammad Azeez interview in: “Regay Kurdystan”, Erbil 1999, no. 673, p. 12.

[16] P. Sosnowski, Path Dependence from Proxy Agent to De Facto State: A History of ‘Strategic Exploitation’ of the Kurds as a Context of the Iraqi Kurdistan Security Policy, “International Journal of Conflict and Violence”, 2022, Vol. 16, pp. 1–13, DOI: 10.11576/ijcv-5688.

[17] O. Yesiltas, Iraq, Arab Nationalism, and Obstacles to Democratic Transition, in: Conflict, democratization, and the Kurds in the Middle East: Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria, eds. D. Romano, M. Gurses, Palgrave Macmillan 2014, pp. 49–50.

[18] K. Yildiz, The Kurds in Iraq…, op. cit., p. 22.

[19] M.M. Dziekan, Irak, religia i polityka, Elipsa 2005, pp. 29–34; J.C. Randal, After such knowledge, what forgiveness? My encounters with Kurdistan, West View Press 1999, p. 163.

[20] L.D. Anderson, G.R.V. Stansfield, The future of Iraq. Dictatorship, democracy of division?, Palgrave Macmillan 2004, p. 56.

[21] M.M. Gunter, The Kurds of Iraq. Tragedy and hope, St. Martin’s Press 1992, p. 37.

[22] D.T. Mason, Democracy, Civil War, and the Kurdish People Divided between Them, in: Conflict, democratization, and the Kurds in the Middle East: Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria, eds. D. Romano, M. Gurses, Palgrave Macmillan 2014, p. 123; Ch. Tripp, Historia Iraku, transl. K. Pachniak, Książka i Wiedza 2009, pp. 250–253.

[23] Resolution 620 (1988) adopted by the Security Council at its 2825th meeting, on 26 August 1988, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/44865?v=pdf, (access 19.05.2018).

[24] R. Fiedler, Iracki Kurdystan w bliskowschodniej strategii Stanów Zjednoczonych (od wilsonowskiego idealizmu do realizmu – Kurdystan w polityce USA), in: Kurdowie i Kurdystan iracki na przełomie XX i XXI wieku, eds. A. Abbas, P. Siwic, Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM 2009, p. 111.

[25] P. Malanczuk, The Kurdish crisis and allied intervention in the aftermath of the second Gulf War, “European Journal of Internation Law”, 1991, Vol. 2, Issue 2, pp. 114–132, DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ejil.a035787.

[26] N. Fenton, Understanding the UN Security Council. Coercion or consent?, Ashgate 2004, p. 39.

[27] An analogous case is Biafra in southeastern Nigeria, where, despite international intervention and periodic development of an autonomous region, the central authorities ultimately restored full control over the territory. See: J.N. Saxena, Self-determination: from Biafra to Bangladesh, University of Delhi 1978, pp. 37–45.

[28] A. Rafaat, US-Kurdish relations in Post-Invasion Iraq, “Middle East Review of International Affairs”, 2007, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 79–89.

[29] Ibidem, p. 81.

[30] M. Kacewicz, Kurdowie chcą niepodległości, ale mają zbyt wielu wrogów [WYNIKI REFERENDUM], Newsweek 2017, https://www.newsweek.pl/swiat/polityka/sa-juz-wyniki-referendum-w-irackim-kurdystanie-92-proc-glosow-na-tak/3806g8y, (access 14.07.2019).

[31] R.J.A. Nanekeli, Battle of Pyrde village, what do we learn from this victory?, [English translation], basnews 2018, http://www.basnews.com/so/babat/474155, (access 04.06.2020).

[32] After all but defeating the jihadists, Iraq’s army turns on the Kurds, The Economist 2017, https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2017/10/21/after-all-but-defeating-the-jihadists-iraqs-army-turns-on-the-kurds?zid=308&ah=e21d923f9b263c5548d5615da3d30f4d, (access 15.07.2019).

[33] In March 2023, an international arbitration tribunal in Paris ruled the oil sale agreements between the Kurdistan Regional Government and Turkey as illegal.

[34] President Macron in meeting with PM Barzani sets terms of Erbil-Baghdad dialogue, Rudaw 2017, https://www.rudaw.net/mobile/english/kurdistan/021220171, (access 14.07.2019); Macron calls for dismantling of all Iraqi militias, The National 2017, https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/macron-calls-for-dismantling-of-all-iraqi-militias-1.680807, (access 14.07.2019).