Krzysztof Śliwiński

Full Article: View PDF

How to cite

Śliwiński K., From Securitization to Securitism. Analyzing the Evolution of the Securitization Theorem. Part I, “Polish Journal of Political Science”, 2025, Vol. 11, Issue 3 (Thematic Issue), pp. 4–16, DOI: 10.58183/pjps.0103TI2025.

ABSTRACT

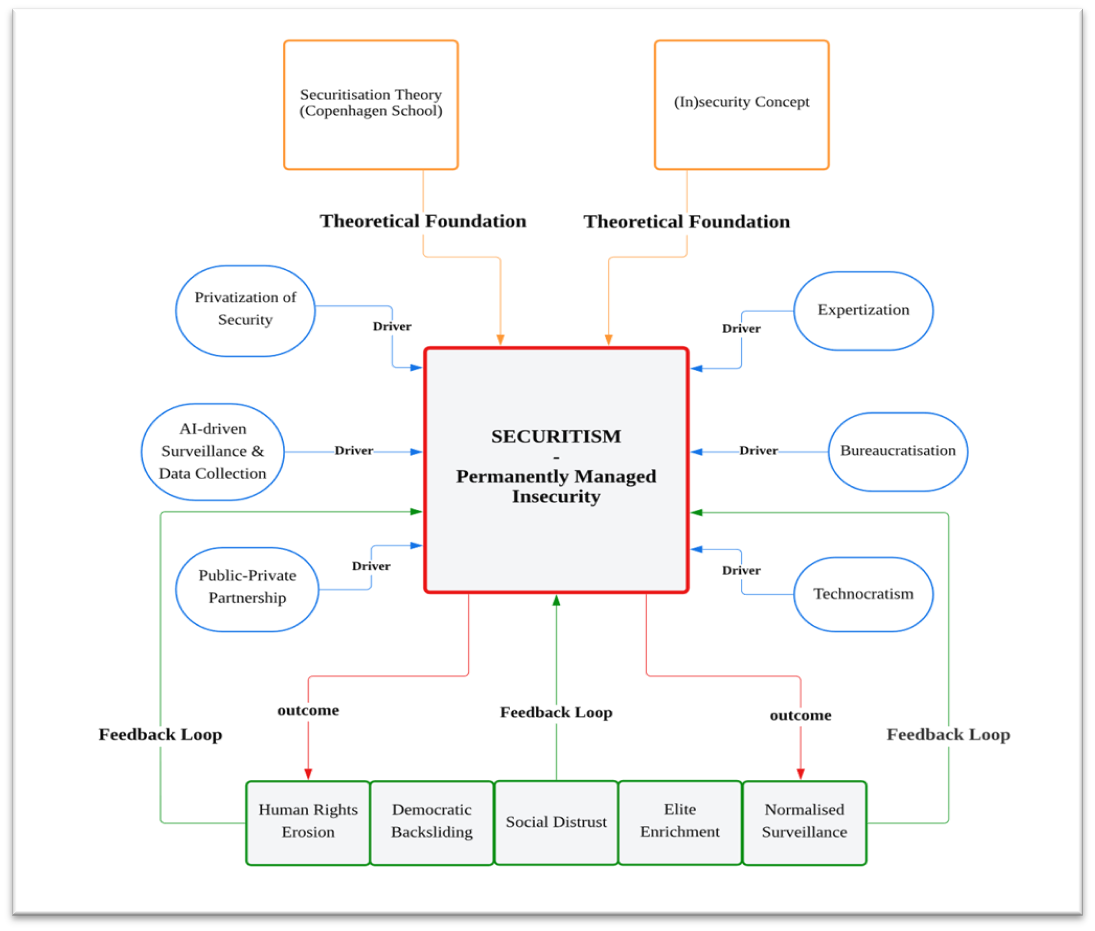

This paper, which is divided into three parts, analyses the evolution of securitization theory and introduces the concept of “securitism,” a permanent state of managed insecurity prevalent in Western societies. Building on the Copenhagen School’s framework and the (in)security concept by Didier Bigo and Anastasia Tsoukala, securitism reflects an illiberal ideology that enables political and economic elites to limit fundamental human rights progressively. This article is the first part of a series devoted to the issue of securitism, which will be published in three consecutive volumes. The first part (which follows below) introduces the reader to the first driver of Securitism – the privatization of security. The following two parts will address the remaining drivers from expertization, through public-private partnership to technocratism. These trends collectively reshape governance, often undermining democratic accountability and individual freedoms. The involvement of powerful transnational corporations and the deployment of advanced AI technologies intensify surveillance and control, further constraining civil liberties. The conclusion of this series will emphasize the critical need for renewed democratic oversight and robust regulatory frameworks to mitigate securitism’s pervasive threats to human rights and democratic governance.

Keywords: securitization, securitism, individual rights

Introduction

“As the journalist and political prisoner, Julian Assange, prophetically predicted in 2011, war is to be part of the New Normal the West has gone on to construct under the cover of lockdown, global ‘boiling,’ the rising cost of energy and every other crisis manufactured into existence by the propaganda agencies of the United Nations: ‘People will reach maturity and adulthood under the understanding that there is always a war. And at that point, war will not be something that is unusual or surprising or horrifying. War will become the New Normal.’ The goal of war in the New Normal, therefore, isn’t victory over a designated enemy but the creation of a permanent state of war that justifies two things. First, war places the warring states under a legal or de facto State of Emergency, justifying the removal of the rights and freedoms of their citizens on a temporary basis it is in the power (and intention) of their governments to extend for as long as the war lasts. We saw this trialled successfully under lockdown, when the West was placed on a war footing in what was universally described as the ‘War on COVID’; and we’re seeing something similar being implemented through Agenda 2030 and the equally fanciful war on what the Secretary General of the United Nations, António Guterres, last year called ‘global boiling.’ Second, war effectively turns the economies of the warring states into centralised command economies, in which all expenditure and consumption fall within the control of the state – which then outsources them to the Government’s preferred transnational companies – and taxes can be increased and government spending cut on the justification of addressing whatever crisis the war serves to create. War, therefore, is first and foremost a means of impoverishment and theft, not only of the populations and resources of the countries in which the war is being waged (Iraq, Libya, Syria, Yemen, Ukraine), but also of the populations of the combatting states (USA, UK, Germany, France, Italy, Canada). The longer the war is waged, the richer are those who invest in it and in return gain access to the taxes, resources, and assets of both sides. Such wars are only ‘won’ when the profit margins do not justify the investment, the most expendable currency of which is, of course, human life.”[1]

This lengthy citation serves as an introduction to the analysis that follows. This paper examines the phenomenon of securitization and proposes a crucial hypothesis: that the processes of securitization carried out in the so-called West have produced a permanent state of insecurity, which is referred to as Securitism.

This paper commences with a brief literature review regarding the securitization theorem. It then presents the hypothesis regarding securitization and defines it. The reader should bear in mind that this research project is divided into three parts, to be published in three consecutive volumes. The first part (which follows below) introduces the reader to the first driver of Securitism – the privatization of security. The following two parts will address the remaining drivers (please see figure 1) from expertization, through public-private partnership to technocratism.

Securitization Theorem

Research on securitization in national security has emerged as a critical area of inquiry due to its expanding role in shaping state policies and international relations beyond traditional military concerns. Since the Cold War, the concept of security has evolved to include non-military sectors such as economic, environmental, and health security, reflecting the diversification of threats states face.[2] The Copenhagen School’s securitization theory, introduced in the late 20th century, has been pivotal in framing security as a social construct enacted through speech acts by political actors.[3] This theoretical evolution has gained practical significance amid global challenges such as terrorism, migration, pandemics, and cyber threats, which have prompted states to adopt securitization strategies with profound political and social implications.[4] For instance, the post-9/11 shift in U.S. Africa policy exemplifies securitization’s impact on foreign policy and the allocation of aid.[5] The increasing securitization of issues such as immigration and pandemics underscores the theory’s relevance in contemporary security discourse.[6]

Specifically, this review concerns the complexities and consequences of securitization processes in national security, particularly the challenges of over-securitization, contested threat perceptions, and the balance between security and human rights.[7] Despite extensive theoretical development, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding the empirical validation of securitization claims, the role of diverse actors, including non-state entities, and the contextual factors that influence securitization outcomes.[8]

Controversies persist over the extent to which securitization leads to effective policy responses versus exacerbating security dilemmas or undermining democratic norms.[9] Moreover, debates continue on the applicability of the Copenhagen School’s framework across different sectors and regions, with critiques highlighting its limitations in addressing routine securitization and everyday security practices.[10] The consequences of these gaps include the potential misallocation of resources and the erosion of civil liberties.[11]

The extensive body of literature on securitization in national security demonstrates the significant evolution of the concept from its classical military focus to encompassing a wide array of sectors, including political, economic, health, environmental, and technological realms. Central to this discourse is the Copenhagen School’s securitization theory, which remains the dominant analytical framework, emphasizing security as a social construct shaped by speech acts and interactions between securitizing actors and audiences. The Paris School and Critical Security Studies provide important theoretical augmentations, illuminating the political technologies of securitization and highlighting the normative and power-related complexities that the Copenhagen School sometimes underappreciates. Together, these frameworks have broadened the understanding of how security issues are socially produced and contested in varied contexts.

Empirical applications reveal that securitization processes are predominantly driven by state elites, political leaders, and, at times, media actors, who frame threats to mobilize political and public support. Nonetheless, audience agency is often underexplored, and recent scholarship advocates a more interactive and process-oriented understanding that accounts for performative and ritualistic elements, as well as the co-constitution of securitizers and audiences. This nuanced view challenges traditional linear models and better captures the dynamics of securitization in practice, including competition between state and non-state actors over legitimacy.

The expansion of securitization into non-traditional sectors such as health, migration, economic stability, and cyberspace reflects the changing security landscape but also introduces risks of over-securitization. While securitizing health crises like pandemics can enhance policy implementation and governance coordination, it may simultaneously facilitate authoritarian tendencies, restrict civil liberties, and marginalize vulnerable groups. Similarly, the securitization of migration often results in the criminalization of migrants and undermines humanitarian considerations. These developments highlight critical tensions between enhancing security and preserving democratic governance and human rights.

Policy implications derived from the literature indicate that securitization can serve as both a catalyst for decisive action and a mechanism for depoliticization and social control. However, many studies note the lack of longitudinal analysis on policy effectiveness and the potential for securitization to entrench restrictive or exclusionary measures. Methodologically, the field is characterized by qualitative discourse analyses, with calls for methodological pluralism and empirical rigor to better capture the complex, multi-level, and evolving nature of securitization processes.

Future research is encouraged to deepen empirical validation, incorporate broader actor and audience perspectives, and critically assess the normative consequences of securitization across diverse security domains. This integrative approach will inform more balanced policy frameworks that reconcile security imperatives with democratic accountability and the protection of human rights.

Securitism Hypothesis

In their seminal book on (in)security (“Terror, Insecurity and Liberty: Illiberal Practices of Liberal Regimes after 9/11”), the authors Didier Bigo and Anastasia Tsoukala define (in)security as a complex, socially constructed process that goes beyond traditional security notions focused solely on survival or protection against war. They argue that (in)security is embedded in the functioning of political and security fields and involves the management of unease by a transnational network of professionals across police, military, intelligence, and private security agencies. This field blurs the traditional boundaries between internal and external security, operating through a logic of exceptionality (“ban-opticon”) that combines exceptional measures, profiling, and normalization, particularly targeting certain groups perceived as abnormal or threatening.[12] Bigo and Tsoukala highlight that (in)security is not a fixed condition but a product of social and political processes involving speech acts (such as securitization) that frame threats and influence policy. However, these acts themselves are shaped by struggles over definitions and resources within the security field. Moreover, (in)security is connected to broader societal anxieties, including those about migration, crime, and terrorism. It is managed by both state and non-state actors, utilizing surveillance and control technologies. Thus, (in)security is understood as a dynamic, relational, and discursive process that produces specific knowledge and practices, which have significant effects on civil liberties, social cohesion, and political governance in liberal democracies, especially in the post-9/11 context.

The hypothesis of securitism builds upon Bigo’s and Tsoukala’s work while simultaneously addressing the research gap identified in the literature review presented in the second part of this paper.

Firstly, both the securitization theorem and the (in)security concept of Bigo and Tsoukala denote dynamic processes. These processes produce certain epistemological limitations, which lead to specific practices, most notably an illiberal type of public policy. Securitism is logically a step further. It is both a state and an effect of securitization and (in)security: a permanent state of highlighted and managed threats that are allegedly always clear and present, allowing for the progressive limitation of fundamental human rights. For obvious reasons, this phenomenon is easier to identify in societies that were once liberal and are rapidly turning into their antithesis, such as the UK or parts of Europe.

Secondly, securitism appears to be more than that. It has evolved into a dangerous ideology, which provides convenient pretexts on the part of political, economic and national/international security elites to undermine fundamental human freedoms. Characteristically, the application of this ideology has been highly privatized in the sense that private companies partner with both national governments and international organizations to provide necessary infrastructure and know-how. Look no further than the case of Palantir.

In that sense, the securitism hypothesis critically engages with the work of Bigo and Tsoukala. Whereas the authors of (in)security, in line with the liberal spirit of the first decade of the 21st century, focus on immigration policies and the surveillance, profiling, and exceptional treatment of ethnic minorities as clear proof of illiberal practices, the hypothesis of securitism is built on a much larger sample.

The securitism hypothesis is visualized in a model proposed in Fig. 1 below. Importantly, part three of this paper will elaborate on the feedback loop presented. Part one of the paper will focus on the privatization of security as one of the drivers that shape securitism.

Figure 1. Securitism Model

Source: Own study.

The Privatization of Security: Constraints on Individual Freedoms

The privatization of security services has emerged as a significant global trend, fundamentally altering the landscape of civil liberties and individual freedoms. As governments increasingly delegate security responsibilities to private entities, critical questions arise regarding accountability, oversight, and the protection of basic human rights. This shift represents a transformation in how coercive power is exercised, often resulting in direct restrictions on movement, speech, and privacy, while creating systemic accountability gaps that weaken democratic governance.

Private security firms often employ exclusionary practices that restrict everyday freedoms in ways that would be constitutionally problematic if carried out by state actors. In São Paulo, research has documented how private guards frequently use non-lethal physical force, detentions, and humiliating treatment in commercial venues and transport terminals, directly curtailing personal liberty and dignity.[13] Similarly, the UK’s “authority to carry” schemes delegate travel-control enforcement to private transport operators, effectively constraining citizens’ rights to enter and exit while reducing legal accountability for these decisions.[14]

The expansion of private security has also facilitated increased surveillance capabilities. Flexible drone and mobile-camera deployments create pervasive monitoring in public spaces that undermine privacy and assembly rights, often without the judicial safeguards typically required for state surveillance activities. These developments demonstrate how privatization can circumvent constitutional protections by placing coercive functions in private hands.[15]

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of security privatization is the creation of accountability gaps that weaken traditional legal and democratic controls. Private security operators function outside the full reach of public legal frameworks, producing what scholars describe as “quilted” security arrangements with blurred responsibilities and insufficient oversight mechanisms.[16]

This problem is particularly acute in international contexts, where studies show that governments often cannot monitor or prevent criminal infiltration of private security firms, leaving abuses largely invisible to oversight bodies.[17] The result is a system in which coercive power is exercised with diminished public accountability and limited recourse for those whose rights are violated.

The privatization of security fundamentally alters the distribution of political authority, with profound implications for democratic processes and the protection of human rights. Cybersecurity and intelligence partnerships with private firms can reallocate political authority away from democratically accountable institutions, reducing public contestability of security decisions and creating informal collaborations that fall outside conventional constitutional constraints.[18]

Critics argue that widespread privatization challenges the foundational promise that states guarantee human rights, producing policy choices that prioritize market efficiency over universal rights protections.[19] This shift represents a reconstitution of authority that may undermine the institutional foundations of the liberal democratic order.

In her seminal book, “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power,” Shoshana Zuboff describes surveillance capitalism as a “coup from above” that overthrows the people’s sovereignty by expropriating critical human rights associated with privacy, autonomy, and democratic participation. These losses are not just about data or privacy but threaten the very possibility of a human future aligned with freedom and democracy. Zuboff makes a particularly striking point by enumerating the rights that are endangered under surveillance capitalism: the right to privacy, or more precisely, decision rights over privacy; the right to the future tense (surveillance capitalism challenges this right by unilaterally rendering lives as data, making individuals objects of behavioral prediction and modification without their awareness or consent); the right to sanctuary (the need for an inviolable refuge or private space is under attack); the right to self-determination and autonomy; and finally, the right to control over knowledge about oneself (surveillance capitalists know everything about individuals, but individuals have little or no access to that knowledge or the ability to contest it).[20]

The privatization of security presents significant challenges to individual freedoms through direct restrictions on civil liberties, the creation of accountability gaps, and the erosion of democratic oversight. While private security may offer certain efficiencies, these benefits come at the cost of weakened rights protections and diminished public control over coercive power. Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive regulatory frameworks, enhanced judicial oversight, and a renewed commitment to ensuring that privatization does not undermine the fundamental rights that democratic societies are designed to protect.

Examples abound, but let us take a closer look at one of them. The COVID-19 pandemic has proven that there is no such thing as individual health, nor is there bodily autonomy. I think we can all recall the official narrative that was pushed globally, how the mRNA vaccinations were going to save the world and end the pandemic. Citizens around the world were continually tested and kept in a state of constant fear. Worse still, they were effectively conditioned by experts, the media, and politicians to distrust each other and treat them with suspicion, if not see them as a source of mortal threat. All of this has brought truly disastrous consequences to communities around the world, breaking basic trust and social bonds.

In the middle stood a cluster of private actors, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer and Moderna; the public-private partnership Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance; the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI); philanthropies like the Wellcome Trust; and investment firms such as BlackRock and Vanguard Group.

In their respective capacities, they provided approximately $10 billion in funding since 2020; co-created Gavi and CEPI; led ACT-A and COVAX for vaccine distribution; lobbied against intellectual property waivers to protect pharmaceutical interests; held direct meetings with leaders such as Angela Merkel; shaped equitable access pledges; developed the leading mRNA vaccine with BioNTech; secured advance purchase agreements via COVAX; lobbied the U.S. and EU for funding; set global procurement standards; influenced EU preparedness policies through more than seven Commission meetings; supported the ACT-A therapeutics pillar; shaped the U.S. Prevent Pandemics Act; and lobbied for $3.5 billion in future funding. They held stakes in mandate-enforcing firms (e.g., Pfizer, Disney) and technology companies (e.g., for vaccine passports) and indirectly influenced corporate policy adoption through shareholder pressure.

Overall, these actors benefited immensely from vaccine mandates, which were seen as amplifying private control over public health compliance. They advocated narrow intellectual property approaches, raised concerns over private veto power in public treaties, and promoted private-sector norms in public health.

To sum up, individual health has been subsumed by public health, which in turn has been subsumed by national security. Latest developments regarding the World Health Organization and proposals to strengthen its role in global public health raise serious concerns about the health autonomy of individuals, driven mainly by constantly curated narratives of impending pandemics and the general vulnerability of human health. In fact, a recent publication by the U.S. Naval Institute asserts that public health has never been treated as a national security concern, which is a significant oversight. The author of the publication puts it painfully, yet dangerously unreflectively: “Protecting the health, safety, and well-being of U.S. citizens is the Government’s first and most important mission. Indeed, the Department of Defense and the vast national security infrastructure supporting it exist because of this mission. It is time to bring the public health community to the table when discussing national security issues.” [21]

References

[1] R. Monti, What is War Really for?, X 2024, https://x.com/robinmonotti/status/1769043695486025894, (access 24.09.2025).

[2] E. Oh, Economic Securitization in the Post-Cold War Era: Navigating the Intersection of Security and Economy, “Democracy and Security”, 2025, pp. 1–19, DOI: 10.1080/17419166.2025.2449644; B. Buzan, O. Wæver, J. de Wilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis, Lynne Rienner Publishers 1997.

[3] M. Stępka, Identifying Security Logics in the EU Policy Discourse The “Migration Crisis” and the EU, Springer 2022; Ł. Fijałkowski, Teoria Sekurytyzacji i Konstruowanie Bezpieczeństwa, “Przegląd Strategiczny”, 2012, No. 1, pp. 149–162.

[4] O. Hjalmarsson, The Securitization of Cyberspace, Lund University 2013, https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=3357990&fileOId=3357996, (access 24.09.2025); G. Karyotis, Non-Traditional Security in Greece: Terrorism, Migration and Securitisation Theory, A thesis submitted for examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), University of Edinburgh 2005.

[5] R.E. Walker, A. Seegers, Securitisation: The Case of Post-9/11 United States Africa Policy, “Scientia Militaria – South African Journal of Military Studies”, 2012, Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 22–45, DOI: 10.5787/40-2-995.

[6] A. Demirkol, An Empirical Analysis of Securitization Discourse in the European Union, “Migration Letters”, 2022, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 273–286, DOI: 10.33182/ml.v19i3.1832; R. Prayuda, et al., The Global Pandemic of COVID-19 as a Non-Traditional Security Threat in Indonesia, “Andalas Journal of International Studies”, 2022, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 63–77, DOI: 10.25077/ajis.11.1.63-77.2022.

[7] Z. Wei, H. Haiyang, The Manifestations, Causes, Impacts and Across Paths of Pan-Securitization, “Journal of Asia Social Science”, 2023, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 37–66, DOI: 10.51600/jass.2023.10.2.37.

[8] Y. Moritani, H. Akiyama, Securitisation behind Persona Non Grata: Implications to the Theory and the Cases Regarding the Russian Invasion of Ukraine in 2022, “F1000Research”, 2023, Vol. 12, pp. 1–19, DOI: 10.12688/f1000research.129876.1; J.F. Mata, Who Can Make Security?: Competition over Securitisation between the State and Non-State Actors in Colombia, “Journal of Human Security”, 2008, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 37–47, DOI: 10.3316/JHS0401037; T. Balzacq, The Three Faces of Securitization: Political Agency, Audience and Context, “European Journal of International Relations”, 2005, Vol. 11, Issue 2, pp. 171–201, DOI: 10.1177/1354066105052960.

[9] O.S. Gaidaev, «Danger: Security»! Securitization Theory and the Paris School of International Security Studies, “MGIMO Review of International Relations”, 2022, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 7–37, DOI: 10.24833/2071-8160-2022-1-82-7-37; W. Jackson, Securitisation as Depoliticisation: Depoliticisation as Pacification, “Socialist Studies”, 2013, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 146–166, DOI: 10.18740/S4NP45.

[10] D.E. Duarte, M.M. Valença, Securitising Covid-19? The Politics of Global Health and the Limits of the Copenhagen School, “Contexto Internacional”, 2021, Vol. 43, No. 2, pp. 235–257, DOI: 10.1590/S0102-8529.2019430200001; E. Brattberg, M. Rhinard, Multilevel Governance and Complex Threats: The Case of Pandemic Preparedness in the European Union and the United States, “Global Health Governance”, 2011, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 1–21.

[11] C. Ogbonna, N.E. Lenshie, Ch. Nwangwu, Border Governance, Migration Securitisation, and Security Challenges in Nigeria, “Society”, 2023, Vol. 60, pp. 297–309, DOI: 10.1007/s12115-023-00855-8.

[12] D. Bigo, A. Tsoukala (eds.), Terror, insecurity and liberty: Illiberal practices of liberal regimes after 9/11, Routledge 2008.

[13] C. da Silva Lopes, Segurança privada e direitos civis na cidade de São Paulo, “Sociedade E Estado”, 2015, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 651–671.

[14] P.F. Scott, Authority to Carry in the United Kingdom: The Right to Travel, the Privatization of Security and the Rule of Law, “European Public Law”, 2017, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 787–810, DOI: 10.54648/euro2017044.

[15] G. Kuiper, Q. Eijkman, The Value of Privacy and Surveillance Drones in the Public Domain: Scrutinizing the Dutch Flexible Deployment of Mobile Cameras Act, “Journal of Politics and Law”, 2017, Vol. 10, No. 5, pp. 35–47, DOI: 10.5539/jpl.v10n5p35.

[16] R. Sarre, T. Prenzler, Policing and Security: Critiquing the Privatisation Story in Australia, in: Australian Policing Critical Issues in 21st Century Police Practice, eds. P. Birch, M. Kennedy, E. Kruger, 1st ed., Routledge 2021, pp. 221–235.

[17] G.H. Turbiville, Private Security Infrastructure Abroad: Criminal Terrorist Agendas and the Operational Environment, Joint Special Operations University Press 2019.

[18] D.R. McCarthy, Privatizing Political Authority: Cybersecurity, Public-Private Partnerships, and the Reproduction of Liberal Political Order, “Politics and Governance”, 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 5–12, DOI: 10.17645/pag.v6i2.1335.

[19] M. Nowak, Human Rights or Global Capitalism: The Limits of Privatization, University of Pennsylvania Press 2017.

[20] S. Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, PublicAffairs 2019.

[21] P.D. Marghella, Public Health Is a National Security Issue, “Proceedings”, 2023, Vol. 149, No. 8, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2023/august/public-health-national-security-issue, (access 24.09.2025).