Esztella Varga

Full Article: View PDF

How to cite

Varga E., US-Turkish Relations During the AKP Era, “Polish Journal of Political Science”, 2025, Vol. 11, Issue 3 (Thematic Issue), pp. 93–118, DOI: 10.58183/pjps.0503TI2025.

ABSTRACT

The relationship between the US and Turkey has had many stages since the end of the Second World War, and a new era arose after the AKP party came to power. Based on the arguments of Buzan, Turkey is not part of any regional security complex (RSC), but is an “insulator state” located between three regional security complexes. However, unlike other insulator states, it has a very active foreign policy. While the US and Turkey are allies in NATO and have military and economic ties, their (geopolitical) interests differ in many areas, thus marking a new era in their bilateral relations when realpolitik may play a greater role. After giving a theoretical introduction and an overview of the global status of both states, as well as a historical background of US-Turkish relations, the paper analyzes the political, economic, military, and societal aspects of their bilateral relations after 2003 using the toolkit of regional security complexes theory. The main argument of the paper is that while diverging foreign policy approaches, different national interests, as well as more active Turkish engagement in the region, have resulted in several rifts in the US-Turkish partnership, the countries remain willing to cooperate and coordinate in the case of converging interests, especially defense and countering terrorism.

Keywords: United States, Turkey, regional security, sectoral analysis

Introduction

The end of the Cold War saw a rise in the importance of regional conflicts and regional powers. Turkey, a country positioned between East and West with a rich history and great influence in its neighborhood, started pursuing an active foreign policy, while the United States began to withdraw from various conflict zones (e.g., Afghanistan), placing more importance on regional forces and neighboring countries. Therefore, the bilateral relationship between the United States of America and Turkey is of great importance, especially in times of escalating regional conflicts. The two countries are traditionally strong partners and have been NATO allies for over seven decades. During the Cold War, Turkey faced the challenge of having the Soviet Union as its neighbor and, in response, turned towards Western allies and strengthened its Western orientation. US-Turkish relations have experienced peak periods (from 1947 until the early 1960s and during the 1980s) but low points as well (in respect of the Johnson letter and issue of Cyprus in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as Iraq in 2003), and their current bilateral relations are troubled by conflicts of interest in many areas too.

The research focuses on the relations between the two states in the twenty-first century, specifically from 2003 onwards. This starting point marks the early stages of the first George W. Bush administration and the first period of government of the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi; AKP), Turkey’s ruling power ever since. During the last two decades, both Turkish and American foreign policy have witnessed several changes in direction and periods of conflict and cooperation in economic, military, and political matters. As discussed in detail in the theoretical part of this paper, we will analyze an asymmetrical relation between a superpower and an insulator state. With the analytical framework of the paper, it is impossible to describe the relationship equally from the perspective of both parties. Therefore, the primary focus will be on Turkey and Turkish interests, and the analysis will be conducted from the Turkish point of view.

The main argument focuses on the securitization policies of Turkey by analyzing its reference objects. The paper tests the argument that the bilateral relations between US and Turkey are primarily shaped by whether Turkey considers certain issues as reference objects. The paper argues that Turkey (in relation to the United States) prioritizes its national interests, especially if the integrity of its territory/nation or ruling power is threatened (e.g., the failed coup in 2016 and PKK-related issues). Moreover, it is even willing to confront the superpower and not only employ soft power elements in defense of these key interests.

While diverging foreign policy approaches and national interests, as well as the more active Turkish engagement in the region, have resulted in several rifts in the US-Turkish partnership, the parties remain willing to cooperate and coordinate in the case of converging interests, especially defense and countering terrorism. The paper aims to conduct an in-depth evaluation of the economic, military, political, and societal aspects of US-Turkish bilateral relations. As we implement the analysis from a security point of view, we use the toolset and concepts (description of the international world order, country categories, etc.) of regional security complexes theory (RSCT). After giving a theoretical introduction and a historical overview of US-Turkish relations, we conduct a sectoral analysis of the bilateral relations of this period. Finally, we conclude and suggest areas for further research.

Theoretical Background

As Turkish foreign policy started to focus more on regional aspects (starting with the “zero problems with neighbors” policy, then adopting a more pragmatic approach in which hard power elements were also used), the analysis requires identifying a theoretical background with a regional focus that addresses not only the global status of the US and Turkey but security concerns as well. Thus, we call on the toolset of RSC theory, which originated in the Copenhagen School, for the concept and the analysis.The Copenhagen School, characterized primarily by the names Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde, takes its name from the headquarters of the Conflict and Peace Research Institute (COPRI), based in Copenhagen. The theory is based on three main pillars: the conceptual pillars of security, sectors, and security complexes.[1] Buzan and Wæver themselves point out in their work “Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security” that the original regional security complexes (RSC) theory was based mainly on the political and military sectors, as these have more impact at a regional level at a short distance, and distance clearly tends to create regional security complexes.[2]

Buzan and Wæver distinguish between the concepts of superpower, great power, and regional power in their theory of RSC. A superpower is one that has extensive capabilities in the overall international system, superior military power, and an economy to support this. In addition, it is recognized by members of the international system and has the legitimacy to represent the values it promotes. At present, this is true only of the United States. The concept of “great power” applies to states that, although not present in all regions, have the economic, military, and political potential to become superpowers in the medium to long term and are treated as such by other states. Regional powers are those states that are dominant in their region but lack global significance. The authors consider superpowers and great powers to be actors at the systemic level, while regional powers are actors at the regional level.[3] We should note here that Turkey is not considered part of any RSC; it is viewed as an insulator state surrounded by three RSCs (Europe, Russia, and the Middle East). For this analysis, we accept the determination of both the global status of the US as a superpower and Turkey as an insulator state.

RSCs are defined as a “set of units whose major processes of securitization, desecuritization, or both are so interlinked that their security problems cannot reasonably be analyzed or resolved apart from one another.”[4] The so-called second-generation thinkers of the 2000s were eager to point out the flaws in this approach in their criticism of the theory, perceiving the sectors of empirical analysis as narrow. In addition, criticisms have been leveled at the lack of theoretical elaboration.[5] However, it can be stated that the original work of Buzan, Wæver, and De Wilde (“Security: A New Framework for Analysis”) provided the theoretical basis for the regional-level analyses of later years.[6]

As the present research does not compare two RSCs but a superpower and an intermediate state, the analytical aspects of the original RSCT are of limited use. However, the method can be applied to the two states when the referent object and the securitizing actor are examined. The focus is on the object (sector, etc.) in relation to which the securitizing actor states that it has the right to use exceptional means, even to break the rules, to ensure its security and survival and how this affects the interests of the other state(s) based on their international interlocking.[7] As stated in the introduction, the main argument that is put to the test is that certain issues Turkey considers as reference objects are primarily shaping US-Turkish relations. The aim of the paper is to identify these issues by conducting a sectoral analysis using the toolset of the RSC theory.

The Global Status of the United States and Turkey

As the theoretical framework has now been defined, it is important to look at the current international world order. Previously, during the Cold War, two superpowers were competing with three other great powers on the international stage. One of the cornerstones of Buzan and Wæver’s theory is that the end of the Cold War contributed greatly to the strengthening of regional security dynamics, which were able to unfold without these superpowers competing. In the post-Cold War world order, the United States is clearly the superpower and currently the only one that makes up the world order alongside the four major powers (China, the EU, Japan, and Russia), i.e., this is a 1+4 world order, which could evolve into a 2+x order, depending on the rise of China or the European Union. Buzan and Wæver see little likelihood of this happening, preferring to see a 0+x order emerge through the slow decline of America in the event of changes. However, even this would not lead to a classical multipolar world order since, in the absence of a superpower, none of the actors would have global interests, only multi-regional ones, and thus, the classical system of balance of power would not emerge, unlike when European powers shared geopolitical territory. Rather, the former would focus on their own regions, RSC, or nearby areas, leading to the general fear that one of the other powers would fill the role of the superpower that has been vacated. But at the global level, the authors still see the survival of the 1+4 order as the most likely outcome.[8] In relation to the position of the United States, the volume highlights – and it is very important to underline this for our analysis – the dominant position of the US in Europe, East Asia, and South America through the various super-regional projects: Atlanticism, Asia-Pacific, Pan-Americanism. These projects generally include strong super-regional economic integration and mutual security and defense aspects, and through their rhetoric and membership designations, the US is perceived as a member of these regions, not as an external, intervening power. This not only prevents the organization of a process of independent, regional integration that could threaten the former’s primacy but also makes analysis more difficult, as the roles of superpower, great power, and regional power are confused. The United States may be a kind of “swing” power, i.e., a power that can play a role in several regions outside its own without being bound to any one region and can vary the depth and form of its engagement according to its interests. As it can withdraw or change its priorities at any time, this gives it the ability to play regions off against each other.[9] Turkey is described by Buzan and Wæver as an insulator state and is discussed in the chapter on the Balkans sub-region. The Balkans have the potential to form a separate regional security complex (RSC) or to be further integrated into the European-EU RSC, but Turkey is not part of this. After the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, two distinct RSCs (or sub-RSCs in the case of the Balkans) emerged in the former territories of the empire: the Balkans and the Middle East, with Turkey as an intermediate state between them. Traditionally, the role of the intermediate states has been passive, as reflected not directly but in a statement by Atatürk: “Peace at home, peace in the world.” In this spirit, it has pursued a policy of westward orientation and remained relatively passive in relation to the countries of the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Balkans.[10]

Reviewing the literature on Turkey as an intermediate state, we find that André Barrinha basically accepts Turkey’s insulator state character, but by integrating it into RSCT, one may also argue that an intermediate state can become a great power without being a member of an RSC. Great power status requires that other states see the potential of the country or its significant influence in the region, but the path of development between regional power and great power is not clear or necessary; the former is not a precondition for the latter.[11]

In addition to examining Turkey’s role as an intermediate state in RSCT, Thomas Diez stresses that Turkish accession to the EU would fundamentally change the situation of the regions, as Turkey would cease to be an intermediate state, thus the three large regional complexes would interact directly, and directly bordering each other.[12] In a review of the work on the subject, Bill Park points out that Turkey is a “swing state” and basically accepts the thesis that Turkey is an intermediate state.[13] Şaban Kardaş, on the other hand, argues for Turkey’s status as a regional power rather than an intermediate state and nuances Buzan and Wæver’s thesis by suggesting that a power can be a member of several RSCs – so that Turkey can belong to the Middle East region as well as the EU – and he rejects the concept of Turkey as an intermediate state.[14]

In relation to intermediate statehood, Buzan and Wæver’s volume describes that how Turkey defines itself in relation to the Eurasian region, which already suggests its much more central role, but what indicates its intermediate statehood is that the Turks are unable to develop this central role themselves. It is worth highlighting that they consider themselves a regional power precisely because they are located at a geographical intersection in the “Bermuda Triangle” of the Balkans, the Caucasus, and the Middle East.[15]

To sum up, we are conducting research that accepts the terminology and concepts of RSCT and seeks to determine the characteristics and behavior of both countries based on the given methodology. Therefore, we now continue with the empirical part of the analysis and focus on a sectoral comparison.

Sectoral Analysis

The sectoral analysis essentially focuses on the four main sectors, on the basis of which the empirical analysis can be carried out: the political, military, economic, and social sectors. Due to the nature of our analysis (comparing a superpower and an insular state, which are geographically not connected), we will not appraise the fifth sector highlighted by the theory, the environmental sector, but focus on the other four sectors. These four sectors have measurable and non-measurable dimensions, so US-Turkish relations must be examined taking these into account. Regarding the four sectors, the analysis pays attention to the following:

- political sector: factors challenging the sovereignty of the state;

- economic sector: trade volumes, energy security;

- military sector: size of army, participation in joint military operations, security issues;

- societal sector: national identity and its preservation.

Within each sector, sub-sectors may be examined in more depth if the reference object is of particular importance to the securitizing actor. The theoretical concept here is constructivist in that it is not important whether the aspect in question is a threat per se, but rather the approach of the securitizing actor: when and under what circumstances the issue is made a security issue. If an aspect is labeled a security issue, the actor has started on the securitization path.[16] For the analysis, we need to separate the security actor and the reference object. In our analysis, Turkey and the United States are the two securitization actors, and the four main sectors explained in the methodological overview, the political, economic, military, and social sectors, are those we can interpret as reference objects. We present the behavior of the two security actors and their relationship by analyzing sub-sectors within each sector. As an insulator state more dependent on its region and the great powers/the superpower, we will mainly focus on the Turkish aspects and primarily try to identify the latter’s reference objects.It should be emphasized that none of the sectors can be interpreted exclusively. Although we try to delimit the sectors taking into account the framework of the analysis, the American-Turkish system of relations is determined by interdependent issues that affect the political- (international institutions, resolutions, foreign policy processes), social- (deeper, even internal political processes), economic- (foreign trade, energy sector) and military- (the two investigated entities are members of the same federal system but their roles and military expenditure, etc. are different) sectors. Therefore, in analyzing each sectoral section, different aspects of the same complex issue may be analyzed.

Political Sector

In the approach of Buzan, Wæver, and De Wilde, the political sector refers to the systemic stability of the social order, i.e., the factors that threaten state sovereignty. Since a separate military sectoral analysis is also provided later, non-military factors are reviewed here. Two levels can be distinguished: threats to individual political forces or threats associated with the systemic level of the international community and international law.[17] We start with defining the key driving forces of the foreign policies of both states and then review their bilateral relations in order to determine the key securitization issues.

The guidelines for Turkish foreign policy were primarily based on the work of Ahmet Davutoğlu, later Turkish Foreign Minister and Prime Minister, published in 2001 in a volume entitled “Stratejik Derinlik” (“Strategic Depth”). Between 2002 and 2015, his foreign policy strategy was the main determinant of Turkish thinking, but this period can be divided into two periods for analysis. The period 2002-2010 was marked by the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 and the neo-conservative “global war on terror” policy of the United States. In this period, soft power and active globalization defined Turkish foreign policy, whose proactivity allowed it to balance Islam, democracy, and secularism successfully.[18]

Davutoğlu argues that Turkey should emphasize, not turn away from, its culturally and historically rich Ottoman heritage and combine it with the republican tradition. In his work, he sees the concepts of geography, history, population, and culture as constant factors that do not change in the short or medium term. In particular, he highlights Turkey’s Ottoman-Turkish historical heritage as a factor shaping foreign policy and identifies it as the reason for more active Turkish engagement in the Balkans and the Caucasus.[19] The years 2010/2011 marked the beginning of a second phase, with the outbreak of the Arab Spring, when previous general foreign policy activity started to be overridden by international events and regional changes, forcing decision-makers to set priorities to pursue a more effective foreign policy. As a sign of this, there has also been a change in the foreign policy instruments being used, from soft to harder power, which can be interpreted as a manifestation of strategic realist thinking.[20] The emerging problems (the refugee crisis, the fight against ISIS, the problem of failed states [Iraq, Syria], regional power struggles, etc.), regional instability, and the end of the ceasefire and peace efforts with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), also indicate the need for change in Turkish foreign policy, indicating the impossibility of continuing the previous approach, which was mainly based on soft power. Ilias I. Kouskouvelis concludes that the “zero problems” foreign policy has failed mainly because it was a way of implementing neo-Ottomanism. Ankara behaved like a heavyweight wrestler trying to intimidate its middleweight neighbors.[21]

Moving on to give a short overview of US foreign policies, we can state that the Bush administration saw the solution in the democratization of the Middle East and sought to obtain international legitimacy for intervention. The Bush Doctrine named “rogue states” and stressed that the United States was prepared to take unilateral action against them. As a presidential candidate, Barack Obama campaigned with the aim of reforming America, and as president, he departed from the previous foreign policy line. Although his declared focus was not primarily foreign policy, he also brought about a significant change there: multilateralism returned to foreign policy rhetoric and practice with the practice of “leading from behind” rather than military intervention overseas. Of course, the economic and financial downturn experienced in this period also played a major role in this, leading to a withdrawal of engagement beyond important US interests in the Middle East and the pivot to Asia.[22]

Donald Trump’s victory in 2016 was one of the signs of the now worldwide phenomenon: the rise of populism; his slogans “America First” and “Make America Great Again” appealed to nationalists and emphasized weakening American power, and his presidency deepened social divisions and the traditional blue-red divide.[23] Joe Biden, promising a different approach from his predecessor, emphasized the importance of the Atlantic partnership and overseas allies and promised to restore the US’s standing in the world. As one of his presidential actions, he rejoined the Paris Climate Agreement, reengaged with the WHO, and firmly stated his aim to repair alliances and lead with diplomacy.[24] However, this was a very ambitious goal, especially with the rising number of challenges his administration has had to face (COVID-19, inflation, the war in Ukraine, relations with China, etc.).

The different approaches to the foreign policies of both states affected their bilateral relations as well. The presidency of George W. Bush, following Clinton, foresaw a similarly good continuation of US-Turkish relations. After the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, Ankara supported Washington in the war on terror and contributed a significant military force to the intervention in Afghanistan from July 2002 to January 2003. Moreover, the Republican tendency was typically to acknowledge the strategic alliance with Turkey.[25] However, 9/11 brought about the policy of the “global war on terror” (GWOT); US interests turned to Iraq in 2003, and the Iraq intervention drove a wedge between allies. At the beginning of 2003, the United States needed Turkey’s help (military support, use of airspace and bases) to prepare for the offensive in Iraq, but on 1 March 2003, the Turkish National Assembly initially did not support the proposal, which led to considerable antipathy towards Turkey among the senior officials of the first Bush administration.[26] The proposal was then accepted a few (very important) days later.

On top of this, US-Turkish relations reached a new low in mid-2003[27] when American soldiers in Sulaymaniyah captured and interrogated Turkish soldiers, accusing them of plotting to assassinate the governor of Kirkuk.[28] The soldiers were released two days later, after high-level talks between Ankara and Washington and the burning of American flags outside the US embassy in Ankara. This incident reinforced anti-US sentiment and found support among the Turkish public, regardless of party affiliation.[29] Anti-Americanism is now generally understood as a response to an imbalance of power, a reaction against the globalization represented by the US, and against American values.

Overall, American-Turkish relations reached a low point during the Bush administration, with each side viewing the other as having been complicit in betrayal and mistrustful due to friction on many issues and often different foreign policy aspirations. Unlike Clinton, Bush attributed more geopolitical importance to Turkey, and the alliance was primarily important to him from the point of view of the security of the region, while Clinton basically assessed Turkey’s importance from a broader, more global perspective.In contrast to the Bush administration’s war on terror, the Obama presidency sought to open a new chapter in US foreign policy, focusing on the US’s main allies rather than the unilateral US concept of power.[30] Obama, continuing the policy of his predecessors, repeatedly and publicly advocated the importance of Turkey’s accession to the EU: in June 2009, for example, on the 65th anniversary of the landings in Normandy, he publicly stressed to the then French President Sarkozy the importance of Turkey’s accession, particularly with a view to strengthening cooperation and cohesion with Muslims. However, in 2010, the Armenian lobby was able to exert increasing pressure on the US Congress to formally refer to the events of the early twentieth century as genocide. As a result, the Turkish side felt betrayed by the Obama administration and even recalled the ambassador (who returned to his post a month later).[31] With the outbreak of the Arab Spring, the evolution of US-Turkish relations was overshadowed by events in the Middle East: in the context of the intervention in Libya, Turkey took a cautious approach and sought to resolve the conflict primarily through diplomacy and mediation in an attempt to avert a humanitarian crisis. This is one of the reasons why Turkey’s participation in the NATO intervention was restrained. It should be noted that the position of other countries opposed to the intervention also changed in the wake of the growing wave of violence in Libya.[32]

Trump’s presidency led to major changes in US-Turkish relations: the US was not committed to the liberal order or Turkey’s transatlantic place in the US system under the “America First” policy. There are diverging strategic objectives between the two countries concerning a number of issues. Disagreements over the United States’ involvement in Iraq and Syria, the Turks’ failure to join the coalition against ISIS until July 2015, and the Turkish suspicion that the US and NATO were behind the 2016 coup attempt all contributed to the deterioration of relations between the two states.

After Biden took office, there had been conflicting interests between the United States and Turkey on a number of issues, and Turkey’s regional engagement and more active foreign policy had, in many cases, provoked Washington’s disapproval. Washington is seeking to counter the growing penetration of China and Russia, while Turkey, whose regional role is mainly dominated by the latter, is developing an increasingly close relationship with Moscow on several issues. The US-Turkish estrangement due to the intervention in Syria turned Turkish attention towards Russia, and in 2017, in line with the Astana process initiated by the Russians, it participated together with Iran.[33] In order to get bilateral relations back on track despite the numerous disputes, presidents Biden and Erdoğan decided to start a strategic mechanism process after their meeting in Rome in 2021. The mechanism officially launched in April 2022 with a meeting of officials in Ankara to discuss various issues regarding economic and defense cooperation and shared interests on regional and global levels.[34] Regarding strengthening NATO and Ukraine since the 2022 invasion as well as supporting the generally pro-Turkish transitional government in Syria after the fall of Assad in 2024, US and Turkey are joining their efforts.[35] Due to the diverging national interests and foreign policy approaches, several conflicts have emerged in the US-Turkish relations over the course of the past two decades. It can be stated that Turkey regards its national interests (especially in its region) as a reference object and often responds to threats to these interests with more than just soft power tools. However, it is also clear that the Atlantic alliance and partnership are vital to Turkey, and it would prefer to focus on its shared interests rather than engage in open confrontation. The US, on the other hand, regards its own interests and the stability of the region as reference objects. Thus, the latter relies on Turkey as its ally from a regional perspective, but to protect the former, it is also willing to use more pragmatic approaches.

Economic Sector

In the sectoral analysis focusing on the economy, we should address the volume and balance of US-Turkish bilateral trade relations from 2003 to 2022 (according to the available data), as well as the foreign direct investment (FDI) and the legal and political framework of economic relations: i.e., trade agreements and other forms of cooperation, and sanctions imposed.

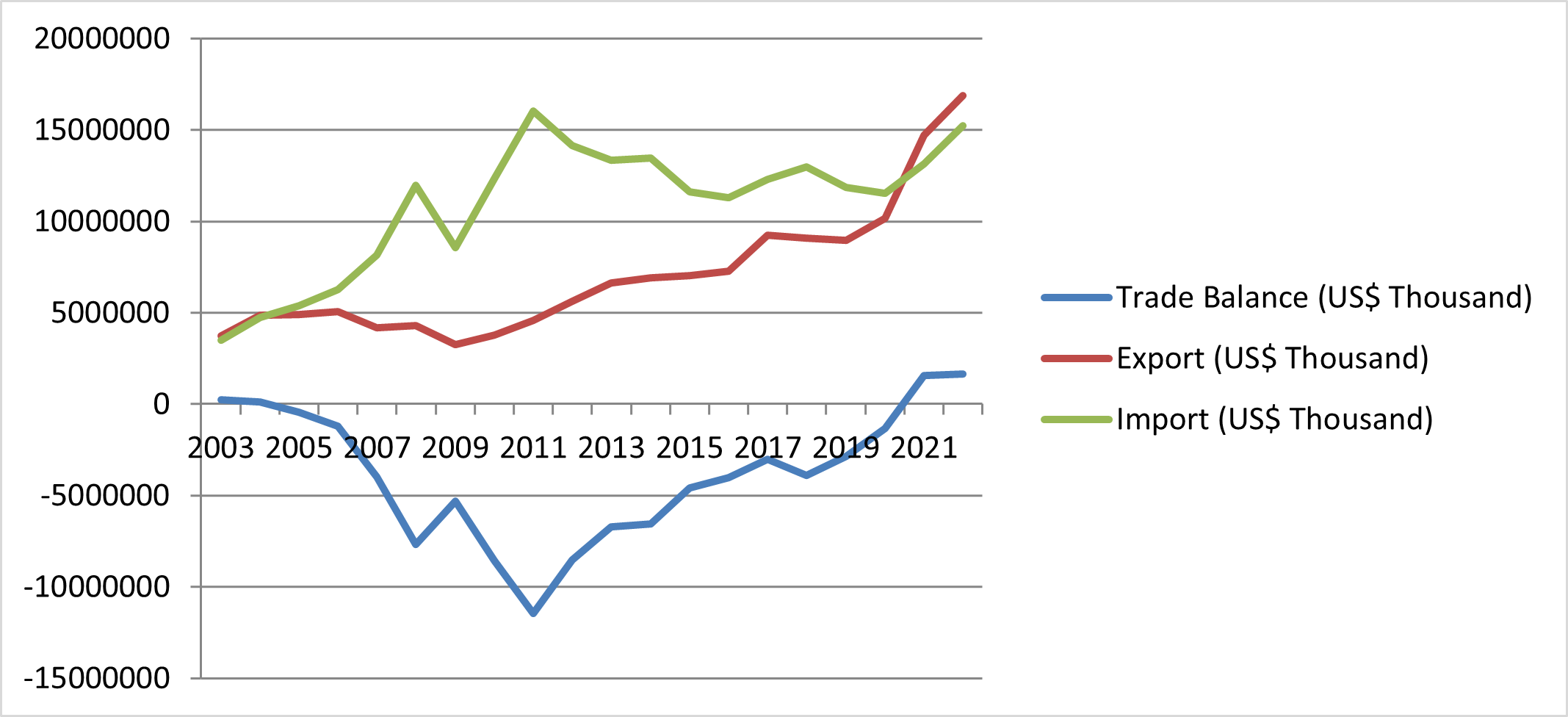

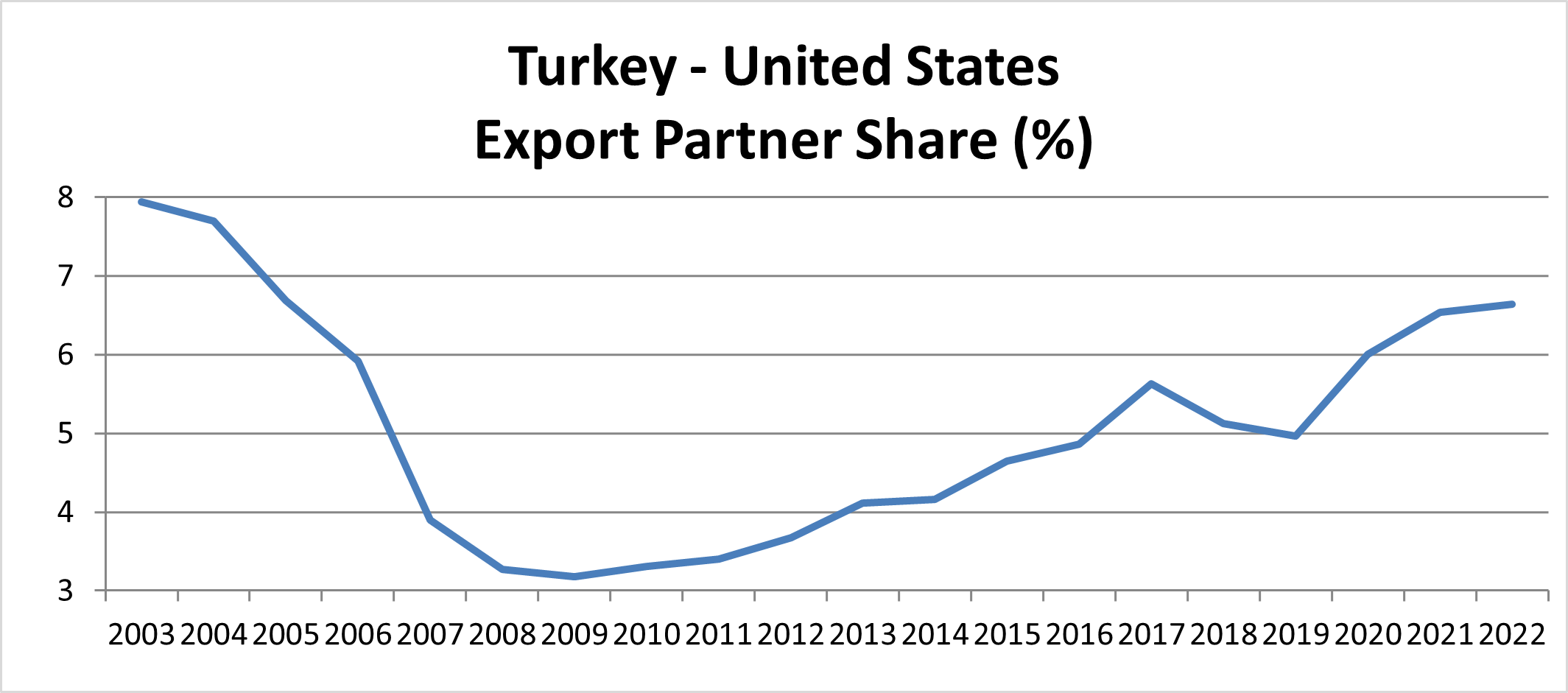

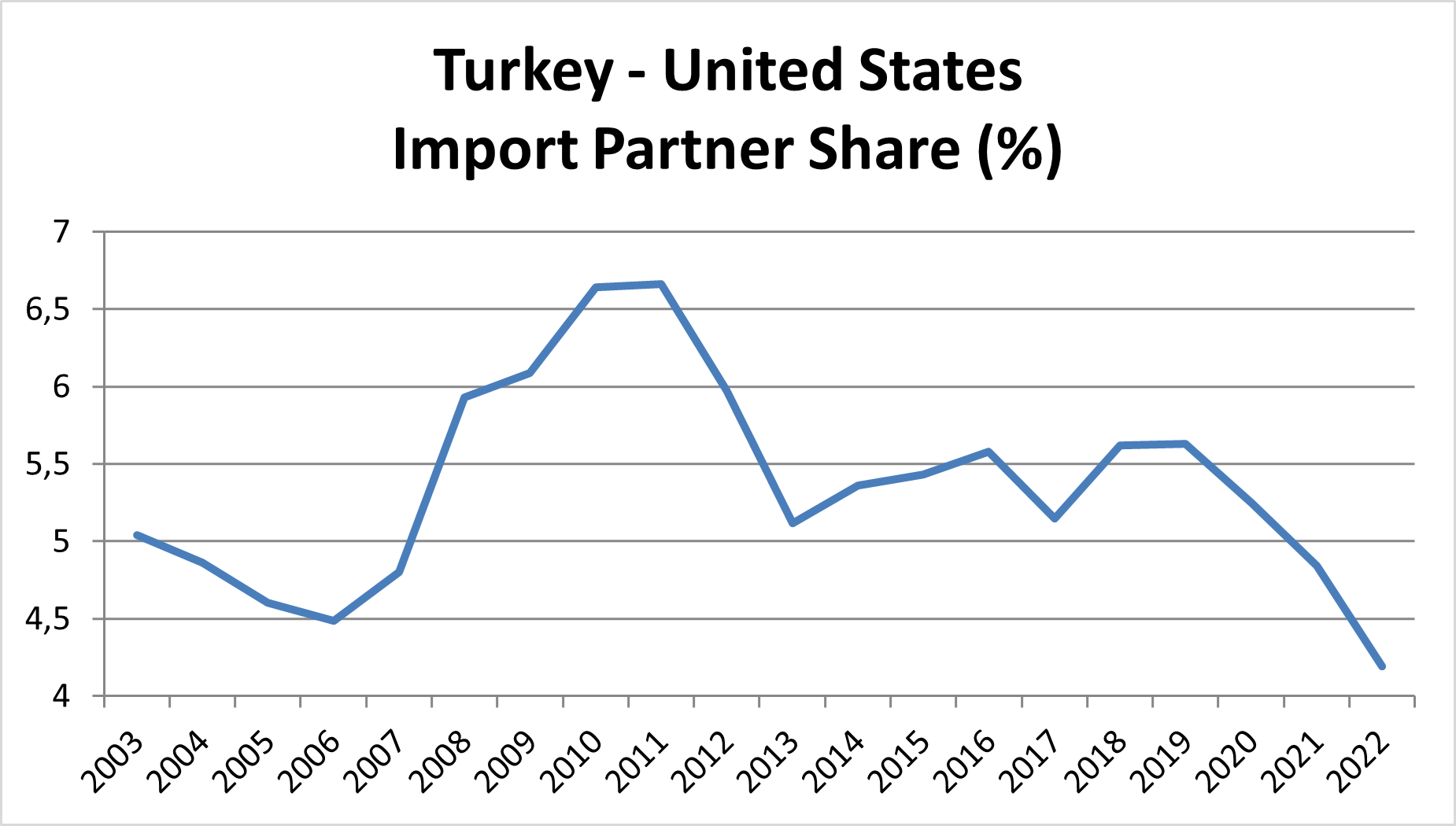

Reviewing the balance of trade and export/import data from 2003-2022, we can see the trend to a growing volume over the past two decades; however, despite the overall expansion, trade relations have been significantly influenced by global economic processes (note the relative low point of 2008-2009 and the peak of 2011, after the world crisis). This trend can be recognized in the US share (as a percentage) of Turkish exports (Figure 2) and imports (Figure 3). As one of Turkey’s main trading partners, this share varies from 3 to 8% over the timeline, with both reaching their lowest volume in 2008/2009, when Turkey experienced a strong economic setback due to the global crisis.

Figure 1. Import and export volume and trade balance of US and Turkey (2003-2022)

Source: Turkey Country Growth v/s World Growth v/s GDP Growth, World Integrated Trade Solutions, https://wits.worldbank.org/countryprofile/en/tur, (access 15.09.2023).

Figure 2. Share of Turkish exports to the US (%)

Source: Turkey Country Growth…, op. cit.

Figure 3. Turkish imports – share of the US (%)

Source: Turkey Country Growth…, op. cit.

Based on the available data, we can state that bilateral trade relations have been influenced by processes of the world economy (economic crises, supply chain challenges) rather than bilateral political or other conflicts. It is also noteworthy that Turkey experienced rapid economic growth in the early 2010s; after the crisis, the economy rebounded, resulting in 9-10% GDP growth in 2010 and 2011. Even after the COVID lockdown and in parallel to raging inflation, the Turkish economy experienced 11.4% GDP growth in 2021 and 5.6% the following year.[36] The volume of foreign direct investment (FDI) should also be highlighted: FDI from the US to Turkey was $5.8 billion in 2022, 7.4% lower than the volume for 2021, while Turkey’s FDI to the US increased by 4.0%, to $2.6 billion in 2022.[37] The second Trump administration imposed “reciprocal tariff” on many of its trade partners, regarding Turkey, a 15% rate was introduced in July 2025, which might effect US-Turkey trade.[38]

The legal framework of the economic and commercial cooperation between the US and Turkey is regulated by international law and is based on the following agreements: The Agreement on Reciprocal Promotion and Protection of Investments of 1990, the Treaty On Avoiding Double Taxation of 1997, and the Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) of 2000.[39]

In our analysis, we should not overlook the ongoing war in Turkey’s neighborhood and Turkish efforts to moderate it. In order to stabilize and resume Ukrainian grain exports during the ongoing war, the Black Sea Grain Initiative was launched in July 2022. It was then renewed two times before it expired on 17 July 2023.[40] Ukraine, traditionally one of the world’s biggest exporters of wheat, sunflower oil, and other crops, supplied almost 33 million tons of grain through the safe corridor in the Black Sea, and food prices dropped nearly by 20%. Food prices began to rise again after Russia rejected its renewal.[41] The grain initiative, brokered by Turkish (and UN) officials, has put Turkey in a strategic position and significantly increased its importance in the eyes of Western allies.[42]

However, due to the sanctions imposed on Russia, tension in Turkish-American relations rose again. The US warned its ally about trade hubs set up to circumvent US sanctions (regarding the export of chemicals, microchips, etc.) and emphasized the risks of doing business in spite of sanctions to the point when the Biden administration imposed sanctions on five Turkish companies on 14 September 2023.[43] This is the second time the US has sanctioned Turkish companies; in April 2023, three Turkish companies were sanctioned by the US for providing financial, material, or technological support to Russian importers.[44]

We must emphasize the relevance of one of the subsectors, namely the energy sector, as energy security is of particular importance for Turkey, and we can consider it a reference object. In 2017, Turkey announced the National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP), which includes 55 action plans intended to reduce primary energy consumption by 14% by 2023. Among other things, this involves steps such as increasing energy efficiency, saving, and investing in industry, services, and agriculture, etc.[45]

The International Energy Agency’s 2021 analysis of Turkey highlights that Turkey is a dynamic country economically and in terms of population, in relation to which market reforms and energy security are key factors. To ensure their viability, the Turks are seeking to develop the domestic exploration and production of natural gas and oil while diversifying available gas and oil resources and infrastructure. The Turkish energy market has also witnessed significant changes over the last decade, mainly in the form of renewable energy sources (hydroelectric power plants) and the nuclear power plant under construction (scheduled to be commissioned in 2023). The large Sakarya gas field in the Black Sea has significantly reduced Turkey’s dependence on gas and created a favorable bargaining position for Turkish companies when renewing gas contracts. At the same time, Turkey has also made progress in the field of infrastructure development; just think of the Turkish Stream pipeline.[46]

In its efforts to diversify its energy sources, Turkey has also faced competition from EU Member States. The Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) was set up by the countries concerned (e.g., Egypt) with the participation of Cyprus and Greece, but Turkey did not become a member. In the context of this conflict, it has become clear that energy security is a reference object for Turkey and that it is acting as a securitizing actor (but primarily in the region and mainly in relation to regional actors). At the same time, it is also clear that for the United States, it is not a reference object and that America does not wish to intervene in the Mediterranean dispute. All the more so since this is not just an energy issue but also part of the Greek-Turkish-Cypriot territorial conflict that has been going on for decades.

A review of the general economic relations between the two countries finds that, despite the conflictual interests in some sectors and aspects, economic relations have prospered and are not causing significant tension in US-Turkish relations. Thus, Turkey is not considering them a reference object in relation to the US.

Military Sector

Turkey was not actively involved in military action following the Korean War (for example, its withdrawal from the Vietnam War included the open condemnation of US policy), but it adopted a greater role with the end of the Cold War. It has supported NATO’s PfP program in other regions of the world (e.g., the South Caucasus) and in the Balkans (Bosnia, Albania, Macedonia, and Kosovo; UNPROFOR-IFOR/SFOR, ALBA, KFOR), but also in the intervention in Afghanistan under the UN Security Council mandate of December 2001.[47] It should be stressed that it was not only joint action that was decisive during this period, but also a shared view of security – namely, that with the end of the bilateral world order, Europe and the US could continue to ensure security together in principle.Davutoğlu’s insight into the issue is that in the post-Cold War period, the US sought to mitigate its conflicts with some European countries through Turkey, and Turkey sought to make up for somewhat faltering European relations with the US alliance. However, concerning the future of NATO, he says that many member states see the Turks as an unsupportive strategic resource (instead, merely as a cheap source of human resource) and that this must change.[48] We begin our analysis of the “reluctant ally” era with President Bush’s global war on terror (GWOT) concept, which was supported by the Turks and EU allies (e.g., the United Kingdom). During the intervention in Afghanistan, the Turkish side was particularly active. Turkey’s role (taking regional command and infrastructure investments) strengthened American-Turkish relations and, through this, EU-Turkish relations. However, several areas caused rifts in both Turkish-European and Turkish-American relations. In the earlier historical overview, we discussed the events in Iraq in 2003 that drove a wedge between the American and Turkish sides. We should also mention the reluctance of European states to provide military assistance and to take action against the PKK, which is a critical issue for the Turks: in the context of the 2003 events in Iraq, several NATO countries (notably Belgium, France, and Germany) opposed action[49] and several European countries refused to declare the PKK a terrorist organization.Here, we must highlight two interventions in which the attitudes of the Turks and the Americans differed: the events in Syria and Libya in 2011. In the latter case, Turkey was initially explicitly opposed to intervention, but when the UK and France also voted in favor, the Turks (like other NATO members) took part in the NATO intervention. Although not involved in carrying out air strikes, the Izmir airbase was the center of operations, and Turkish forces were also involved in drawing up the mission framework and monitoring the embargo on Gaddafi’s forces.[50] Turkey, and Erdoğan himself, initially had a very good relationship with Assad and tried to play a mediating role when the conflict erupted, but soon turned away from Assad and have since supported the rebels, but primarily due to their own interest in dampening Kurdish aspirations for autonomy. In October 2019, the Turkish military intervention met strong US and European opposition, and under US pressure and sanctions, the Turks finally ceased it. In his analysis, Özgür Özdamar sees the Syrian conflict as one of the main reasons for the deterioration of bilateral relations, and this can clearly be highlighted.[51] One of the main differences emerged regarding the Syrian Kurdish groups: Turkey considered the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and People’s Protection Units (YPG) the extensions of PKK in Syria, while the US was arming them as part of the forces allied against ISIL (Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant). The Turkish military operations in northern Syria in 2016 (Operation Euphrates Shield) and 2018 (Operation Olive Branch) mainly targeted these Syrian Kurdish groups, thus, according to the US’ point of view, weakening their efforts against ISIL.[52] It is also noteworthy that Mustafa Kutlay and Ziya Öniş also describe the Middle East and North Africa as geopolitically highly unstable and the center of great power rivalry due to weakening US commitment.[53]

The purchase of the S-400 missile system by the Turks was one of the most defining issues of the Trump administration from a Turkish-American perspective. The Turks felt that their military security was not getting the attention it deserved when problems arose over the purchase of Patriot missiles and technology transfer, leading them to turn first to Chinese and then Russian technology. Eventually, the Russian S-400 missile system was purchased, which created security and compatibility tensions within NATO and further strained the US-Turkish relationship.[54] The purchase has strengthened Russian-Turkish relations but caused significant damage to US-Turkish and Turkish relations with NATO, in addition to raising security and compatibility concerns.[55] Trump blamed the previous administration for blocking the purchase of the Patriot system and tried to avoid imposing sanctions for as long as possible, but his rhetoric on Turkey was tough and generated recurrent conflict at the bilateral level – so much so that in December 2020, the US finally imposed sanctions on its Turkish ally.[56]

Another serious issue has arisen within NATO because of the growing military pressure due to the war in Ukraine. In May 2022, Finland and Sweden stated their intention to become members of NATO despite their long history of neutrality.[57] Most of the NATO members ratified their memberships within a relatively short time; however, Hungary and Turkey delayed the process of the Swedish application. The reason for the Turkish block was in connection with the PKK and security issues (strengthened enforcement of the Swedish anti-terrorist law); however, from time to time, the issue was connected by the Turkish narrative with EU accession or the purchase of F16s.

After the NATO summit in July 2022, a trilateral memorandum was signed to address Turkey’s security issues. The issue often connected to the purchase of F-16 jets. The Turks, having failed to purchase the F-35s and being removed from the program, are eager to modernize their army and upgrade their jets, especially as Turkey is a user as well as a (former) producer of these aircraft. It is noteworthy that the Turkish Presidency of Defense Industries already signed a contract with Turkish Aerospace Industries (TUSAŞ) to create a national combat aircraft in 2016.[58] Moreover, by November 2024, TUSAŞ is said to able to provide upgrades for the F-16 jets domestically.[59]

In light of the above, the Turks need at least tacit support from their Atlantic ally to act effectively, even in regional conflicts. The prior interventions in Syria suggest that Turkish interests do not coincide with US interests in many cases, but Turkey’s capacity to act is not as great as it would like in the area of reference. Turkey repeatedly chooses confrontation to defend its interests and territorial integrity and is willing to use tougher means against both its US and European allies. Therefore, we must label this a reference object and state that Turkey acts as a securitizing actor in relation to the US, causing tensions to rise and making this aspect one of the key factors in the analysis.

Societal Sector

According to Buzan’s interpretation, it is difficult to define the security actor here since it is not only or not primarily states that constitute societies. Thus, any social group whose security (identity) is threatened can be the object of reference here. These are mainly nations.[60] As regards the societal sector, Turkey, as a securitizing actor, considers preserving its national unity as its reference point since it has been striving to survive as a united Turkish nation since the end of the Ottoman Empire. This is nuanced by the issue of Kurdish nationality (and the human rights aspects that arise in relation to it), and the issue is clearly seen as a security threat to the Turkish nation. There has been and continues to be much criticism of the Turkish leadership for its failure to provide members of the Kurdish nationality with the conditions for the use of their national language. This has changed since the AKP government came to power, with Erdoğan taking several steps to allow the use of Kurdish: since 2006, Kurdish has been allowed on television, and in 2009, the first Kurdish television channel was launched, broadcasting 24 hours a day in Kurdish. The 2013 ceasefire agreement with the PKK was another soft power security measure for achieving this social security dimension. After the ceasefire broke in July 2015, a violent decade followed where Ankara refused further talks until PKK laid down their arms, which eventually happened in early 2025.

This issue is particularly significant when viewed through the lens of the geopolitical approach. Davutoğlu highlights the vacuums created after the collapse of the Soviet Union and outlines the importance awarded to protecting Turkish interests (related to insecurity on Turkey’s immediate land border).[61] In addition, the increasing pan-Turkism, Eurasianism, nationalism, extremism, and Islamism in Turkish domestic politics are also signs of social division. Increasingly strong anti-European and anti-US voices emphasize the development of an alternative sphere of influence based on the Turkish-rooted peoples of the region, and the 11-16% parliamentary representation of proponents of this position is evidence of its wider social support.

During the analysis of Turkish domestic politics and its effect on the societal sector, we must also take the Fethullah Gülen issue into consideration, especially as it has a significant impact on US-Turkish relations, too. Gülen used to be a supporter of the early AKP and Erdoğan. He left Turkey in the late 1990s after the military coup and has lived in the USA ever since. As a Sufi imam, he promoted Islamic modernism and a more pious society, demonstrating much in common with AKP’s goals. In the early period, cooperation and support between the followers of Gülen (the “Gülenists”) and AKP flourished, although they sought to achieve common goals using different means. While Gülen prioritized the nongovernmental sector (civil sector, schools, etc.) and emphasized faith, AKP and Erdoğan prioritized political Islam. Soon, Gülen established a wide network of followers – Gülenists working in a variety of sectors and dominating Turkish politics alongside AKP since 2002. However, after a dispute concerning the 2011 elections (when dozens of Gülenists were not included in the AKP list as Erdoğan tried to prevent the rise of a rival power center) and the government initiative to close Gülenist educational centers in 2013, members of the movements soon became dire enemies. Domestic tension escalated due to the failed coup attempt in 2016 when Erdoğan and AKP immediately named Gülen as the mastermind behind the coup. The government began a systematic purge of (alleged) Gülenists from the ranks of civil servants, military officers, teachers, journalists, and government employees. More than 150,000 people lost their jobs, approx. 80,000 people faced trials, and around 1,500 civil institutions were closed.[62]

The human rights impacts of this domestic coup and the following purge triggered a firm warning from the US, especially as an American pastor, Andrew Brunson, was also arrested during the retaliation. Donald Trump used Twitter (now X) to file warnings (even mentioning possible sanctions) to Erdoğan and to urge the release of Brunson. Also, the leader of the Gülen movement (considered a terrorist organization by the Turkish government), Fethullah Gülen, resided in the USA until his death in October 2024, despite Erdoğan having requested his extradition several times.

The reference object for our analysis is still the unity of the nation of Turkish society, in relation to which we must highlight another factor that has been present for decades, Sévres syndrome, which has been a constant in Turkish thinking since the First World War. This refers to the emphasis on Turkish victimhood that is still present and can be linked to the aforementioned anti-EU and anti-US sentiment.

As there are several conflicts in this sector, and it is one of Turkey’s main security concerns, we may state that Turkey is willing to use harsher means to defend its interests and confront the US openly. However, the US is approaching the issue more carefully (and is no securitizing actor by any means), as some vital parts of this complex sector are the internal affairs of Turkey. Nevertheless, under the different administrations, the US has subtly but firmly expressed its concerns regarding Turkey’s actions: Trump used Twitter to reprimand, while Biden decided not to invite Turkey to the Summit for Democracy and has expressed his concerns about human rights in Turkey.

Conclusion

As we have seen above, the bilateral relations between the United States of America and Turkey are of great importance, especially in times of escalating regional conflicts. The alliance is no longer the same as during the Cold War. Through the sectors of politics, economy, military, and society, we have analyzed the main reference objects for Turkey in their bilateral relations. The paper confirms, that for Turkey, internal affairs (PKK and the Kurdish question, the failed coup attempt of 2016), aspects of the political sector that are strongly connected to internal affairs (e.g., intervention in Syria), and the military sector play vital roles in securitizing efforts, thus shaping (and causing fractures in) US-Turkish bilateral relations.

Although both countries are still committed to the Atlantic partnership and cooperation under the umbrella of NATO, their national interests (reference objects in our analysis) require them to confront each other regarding several issues. This confrontation prompts Turkey to look for alternative ways to avoid deepening conflicts (see the goal of creating national combat aircraft to circumvent the F-16 issue) with the global superpower because, as an insulator state, its capacity is not yet that of a regional or great power. Moreover, we have seen that (in the case of mutual or converging interests, and if the reference object is of little or no interest to the other party), they are willing and able to cooperate and have fruitful partnerships (as seen during the analysis of the economic sector, in the political sector with the US’ continuous support of Turkish EU-membership, and the military sector detailing joint operations within NATO).

Regarding the overall dynamics associated with the bilateral relations of the two states, after a peak period in the 1980s and 1990s, a new era began: pragmatic approaches and realpolitik are now playing the leading role. The main finding of this paper is that while diverging foreign policy approaches, different national interests, as well as the more active Turkish engagement in the region, have resulted in several rifts in the US-Turkish partnership, they remain willing to cooperate and coordinate on converging interests, especially such as defense and countering terrorism. This approach also gives us a chance to assess the future course of their bilateral relations and determine the trends associated with a more pragmatic relationship.

Acknowledgments

This study is an outcome of the Geopolitical Frontiers research project of the Future Potentials Observatory, MOME Foundation.

References

[1] H. Stritzel, Security in Translation: Securitization Theory and the Localization of Threat, Palgrave Macmillan 2014, pp. 11–14.

[2] B. Buzan, O. Wæver, Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security, Cambridge University Press 2004, p. 16.

[3] Ibidem, pp. 34–38.

[4]Ibidem, p. 44.

[5] H. Stritzel, Security in Translation…, op. cit., p. 12.

[6] R.E. Kelly, Security Theory in the ‘New Regionalism’, “International Studies Review”, 2007, Vol. 9, No. 2, p. 206, DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2486.2007.00671.x.

[7] B. Buzan, O. Wæver, Regions and Powers…, op. cit., p. 71.

[8] Ibidem, pp. 446–455.

[9] Ibidem, pp. 455–456.

[10] Ibidem, pp. 377–393.

[11] A. Barrinha, The Ambitious Insulator: Revisiting Turkey’s Position in Regional Security Complex Theory, “Mediterranean Politics”, 2014, Vol. 19, Issue 2, pp. 167–170, DOI: 10.1080/13629395.2013.799353.

[12] T. Diez, Turkey, the European Union and Security Complexes Revisited, “Mediterranean Politics”, 2005, Vol. 10, Issue 2, p. 173, DOI: 10.1080/13629390500141600.

[13] B. Park, Turkey’s ‘New’ Foreign Policy: Newly Influential or Just Overactive?, “Mediterranean Politics”, 2014, Vol. 19, Issue 2, p. 161, DOI: 10.1080/13629395.2014.915915.

[14] S. Kardaş, Turkey: A Regional Power Facing a Changing International System, “Turkish Studies”, 2013, Vol. 14, Issue 4, pp. 646–647, DOI: 10.1080/14683849.2013.861111.

[15] B. Buzan, O. Wæver, Regions and Powers…, op. cit., pp. 377–395.

[16] Ibidem, pp. 71–72.

[17] B. Buzan, O. Wæver, J. De Wilde, Security: A New Framework For Analysis, Lynne Rienner 1998, p. 141.

[18] E. Fuat Keyman, Resetting Turkish foreign policy in a time of global turmoil, in: The Routledge Handbook of Turkish Politics, eds. A. Özerdem, M. Whiting, Routledge 2019, p. 383.

[19] A. Davutoğlu, Stratejik Derinlik. Türkiye’nin Uluslararası Konumu, Küre Yayinlari 2001, pp. 18–24.

[20] E. Fuat Keyman, Resetting Turkish foreign…, op. cit., pp. 385–387.

[21] I.I. Kouskouvelis, Turkey, Past and Future The Problem with Turkey’s „Zero Problems”, “Middle East Quarterly”, 2013, Vol. 20, No. 1, p. 56.

[22] M. Clementi, The Stability of the US Hegemony in Times of Regional, in: US Foreign Policy in a Challenging World – Building Order on Shifting Foundations, eds. M. Clementi, M. Dian, B. Pisciotta, Springer 2018, pp. 109–114.

[23] T. Wojczewski, Trump, Populism, and American Foreign Policy, “Foreign Policy Analysis”, 2020, Vol. 16, Issue 3, pp. 292–311, DOI: 10.1093/fpa/orz021.

[24] Remarks by President Biden on America’s Place in the World, The White House 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/02/04/remarks-by-president-biden-on-americas-place-in-the-world/, (access 16.09.2023).

[25] F. Türkmen, Turkish–American Relations: A Challenging Transition, “Turkish Studies”, 2009, Vol. 10, Issue 1, p. 114, DOI: 10.1080/14683840802648729.

[26] B. Park, US—Turkish Relations: Can the Future Resemble the Past?, “Defense & Security Analysis”, 2007, Vol. 23, Issue 1, p. 41, DOI: 10.1080/14751790701254466.

[27] The incident was the basis for the 2006 film Valley of the Wolves: Iraq.

[28] A.E. Çakir, The United States and Turkey’s Path to Europe: Hands across the Table, Routledge 2016, p. 177.

[29] F. Türkmen, Turkish–American Relations…, op. cit., p. 123.

[30] I. Kalin, US–Turkish relations under Obama: promise, challenge and opportunity in the 21st century, “Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies”, 2010, Vol. 12, Issue 1, p. 93, DOI: 10.1080/19448950903507529.

[31] A.E. Çakir, The United States and…, op. cit., pp. 226–232.

[32] N. Çetinoğlu Harunoğlu, A Turkish perspective on the ethics of ‘safe zone’: the evolution of the concept in Turkish–American relations from Iraq (1991–2003) to Syria (2012–2016), “Journal of Transatlantic Studies”, 2019, Vol. 17, p. 444, DOI: 10.1057/s42738-019-00032-y.

[33] P.K. Baev, K. Kemal, An ambiguous partnership: The serpentine trajectory of Turkish-Russian relations in the era of Erdoğan and Putin, The Center on the United States and Europe at Brookings – Turkey project policy paper, number 13, 2017.

[34] Türkiye-U.S. Joint Press Release on the Strategic Mechanism, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Türkiye, https://www.mfa.gov.tr/no_-117_-turkiye-abd-stratejik-mekanizmasi-hakkinda-ortak-basin-aciklamasi.en.mfa, (access 15.09.2023).

[35] J. Zanotti, T. Clayton, Turkey (Türkiye): Major Issues and U.S. Relations, Congressional Research Service 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R44000#fn55, (access 22.09.2025).

[36] The World Bank in Türkiye, World Bank Group, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/turkey/overview#3, (access 16.09.2023).

[37] Republic of Türkiye Trade Summary, Office of the United States Trade Representative, https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/europe-middle-east/europe/Turkey, (access 28.09.2023).

[38] J. Zanotti, T. Clayton, Turkey (Türkiye): Major…, op. cit.

[39] Bilateral and Economical Relations between Türkiye and the United States of America, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Türkiye, https://www.mfa.gov.tr/relations-between-turkiye-and-the-united-states-of-america.en.mfa, (access 15.09.2023).

[40] Black Sea Grain Initiative Joint Coordination Centre, https://www.un.org/en/black-sea-grain-initiative, (access 12.09.2023).

[41] How is Ukraine exporting its grain now the Black Sea deal is over?, BBC 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-61759692, (access 27.09.2023).

[42] N. Morgado, E. Varga, Geopolitical continuity? An analysis of the Turkish Straits and Russian ambitions, “Southeast European and Black Sea Studies”, 2025, pp. 1–17, DOI: 10.1080/14683857.2025.2515731.

[43] H. Pamuk, D. Psaledakis, US sanctions 5 Turkish firms in broad Russia action on over 150 targets, Reuters 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-sanction-five-turkey-based-firms-broad-russia-action-2023-09-14/, (access 16.09.2023).

[44] Treasury Targets Russian Financial Facilitators and Sanctions Evaders Around the World, US Department of the Treasury 2023, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1402, (access 16.09.2023).

[45] National Energy Efficiency Action Plan 2017-2023, International Energy Agency 2022, https://www.iea.org/policies/7964-national-energy-efficiency-action-plan-2017-2023, (access 22.09.2023).

[46] National Energy Efficiency Action Plan 2017-2023– Turkey 2021, International Energy Agency, https://www.iea.org/reports/Turkey-2021, (access 22.09.2023).

[47] Partnership for Peace programme, NATO, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_50349.htm, (access 21.09.2023).

[48] A. Davutoğlu, Stratejik Derinlik. Türkiye’nin…, op. cit., pp. 233–237.

[49] NATO and the 2003 campaign against Iraq, NATO 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_51977.htm, (access 21.09.2023).

[50] NATO and Libya (February – October 2011), NATO 2012, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_71652.htm, (access 21.09.2023).

[51] Ö. Özdamar, Role Theory in Practice: US–Turkey Relations in Their Worst Decade, “International Studies Perspectives”, 2024, Vol. 25, Issue 1, p. 55, DOI: 10.1093/isp/ekad014.

[52] T. Oğuzlu, Turkey and the West: Geopolitical Shifts in the AK Party Era, in: Turkey’s Pivot to Eurasia Geopolitics and Foreign Policy in a Changing World Order, eds. E. Erşen, S. Köstem, Routledge 2019, pp. 21–22.

[53] M. Kutlay, Z. Öniş, Turkish foreign policy in a post-western order: strategic autonomy or new form of dependence?, “International Affairs”, 2021, Vol. 97, Issue 4, p. 1088, DOI: 10.1093/ia/iiab094.

[54] K. Kirişci, US–Turkish relations in turmoil, in: The Routledge Handbook of Turkish Politics, eds. A. Özerdem, M. Whiting, Routledge 2019, pp. 406–408.

[55] P.K. Baev, K. Kemal, An ambiguous partnership…, op. cit.

[56] US sanctions NATO ally Turkey over Russian S-400 defence missiles, Al Jazeera 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/12/14/us-sanctions-nato-ally-Turkey-over-russian-missile-defence, (access 15.09.2023).

[57] P. Chatterjee, How Sweden and Finland went from neutral to NATO, BBC 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-61397478, (access 13.09.2023).

[58] R. Outzen, P. Dost, A looming US-Turkey F-16 deal is about much more than Sweden’s NATO bid, Atlantic Council 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/Turkeysource/a-looming-us-Turkey-f-16-deal-is-about-much-more-than-swedens-nato-bid/, (access 15.09.2023).

[59] J. Zanotti, T. Clayton, Turkey (Türkiye): Major…, op. cit.

[60] B. Buzan, O. Wæver, Regions and Powers…, op. cit., pp. 70–71.

[61] A. Davutoğlu, Stratejik Derinlik. Türkiye’nin…, op. cit.

[62] S.J. Flanagan, et al., Turkey’s Nationalist Course: Implications for the U.S.-Turkish Strategic Partnership and the U.S. Army, RAND Corporation 2020, pp. 15–17.