Andrea Zanini

Full Article: View PDF

How to cite

Zanini A., Between Hospitality and Diplomacy. Accommodating Foreign Delegations during the 1922 Genoa Conference, “Polish Journal of Political Science”, 2022, Vol. 8, Issue 1, pp. 30–49, DOI: 10.58183/pjps.01082022.

ABSTRACT

During the 1922 Genoa International Economic Conference, the hotels of the city and neighboring coastal resorts played a pivotal role in many respects, including diplomatic activity. They accommodated representatives of the participating countries and hosted related gala events, as well as formal and informal meetings and discussions between delegations, individual figures, or selected groups. Moreover, the most striking and astonishing outcome of the Genoa Conference, namely the Rapallo Treaty between Russia and Germany, was signed right inside the hotel that welcomed one of the delegations.

By analyzing these issues, the article deals with the existing academic literature on the role played by hotels as scenes of historical events and within the context of international relations. It also highlights how hosting a diplomatic gathering of such resonance may promote tourism and enhance the image of leading hotels.

Keywords: luxury hotels, big events, tourism promotion, international relations, post-WWI order, Rapallo Treaty

Introduction

The International Economic Conference, which was held in Genoa from 10 April to 19 May 1922, represented one of the most important gatherings of international diplomacy after the Peace of Versailles (1919). It was to be a milestone in setting a new course in European economic and financial relations as well as resuming diplomatic and trade relations with Russia after the fall of the Tsarist rule (1917). However, as is well known, the results fell far short of expectations, in part because of a sudden turn of events: the Rapallo Treaty between Russia and Germany secretly concluded just a few days after the beginning of the Conference.[1]

When Genoa, an industrial and port city in the north-western part of Italy, was chosen to host an international event of such magnitude, one of the first problems the Italian authorities had to face was organizing accommodation for foreign delegations. Besides providing spaces for the official works of the Conference, it was necessary to welcome the representatives of the many participating countries and their staffs of collaborators, as well as to house dozens of correspondents of national and foreign newspapers that would cover the event. Hotels played a crucial role in this respect, particularly the large, luxury ones.[2]

Nevertheless, it should be pointed out that it was not merely a matter of accommodation capacity. Once suitable lodging facilities had been identified, it was necessary to carefully plan how to allocate the delegations to various hotels. Of course, the delegations’ numerical size and qualitative composition could not be ignored; however, other aspects related to the sphere of international relations and geopolitical balances also had to be considered in managing hospitality issues.

Moreover, from the point of view of the hosting country, welcoming such an international gathering could constitute an important visiting card and a way to strengthen its political weight in the international arena.[3] It also could be an opportunity to promote tourism in the area where the Conference was going to take place, although this latter instance occupied a very marginal position in the Italian tourism policy of the time.[4] Last but not least, the Conference also represented a chance for the leading hotels that welcomed prominent figures, or key-related events, to gain visibility at the international level, thus enhancing their image and reputation.

A century later, the symbolic places of the Conference, including the large, luxury hotels, still preserve a cultural value related to that event. Although these aspects have fallen into oblivion in many cases, they deserve to be considered even from a historical cultural heritage enhancement perspective.

Although the studies on the 1922 Genoa Conference have not completely neglected these issues, an overall view is still lacking. The aim of this paper is, therefore, twofold. On one hand, it allows us to shed light on little-known aspects related to that specific event and its cultural legacy. On the other, it contributes to enriching existing literature on the relationships between the hotel industry and diplomatic activity.

This article is organized as follows. The first paragraph describes the connections between hotels and international relations; the second one delves into the issue related to the selection of the hotels that hosted foreign delegations and official events during the Genoa Conference; the third paragraph focuses on the case of the Imperial Palace Hotel, where the Rapallo Treaty was signed, while the last one provides a conclusion.

Luxury hotels and diplomacy

Large, luxury hotels – so-called grand hotels or palace hotels – that cropped up in the mid-nineteenth century in major European cities and tourist resorts were the outcomes of the social and cultural transformations that took place throughout that period and the growing demand for hospitality from upper-class travelers and tourists.[5] Initially, these hotels were influenced by two different styles of hospitality. The first one was inspired by the French penchant for court pomp and ceremony, while the second one was influenced by the English taste for modern technologies arising from the industrial revolution. It was the well-known Swiss-born hotelier César Ritz (1850-1918) who, at the end of the 19th century, succeeded in merging these styles into a new model of luxury hospitality addressing the cosmopolitan clientele, whose watchwords were excellence and exclusivity. Specifically, Ritz’s model combined elegance, comfort, hygiene, and privacy with excellent cuisine. For these reasons, it quickly established itself as a successful model, thus widely imitated.[6]

As a result, the luxury hotels of the Belle Époque were characterized by the magnificence of common spaces such as foyers, staircases, and vestibules, by a series of interconnected salons with distinct functions (dining room, ballroom, reading room, etc.) and a large number of spacious bedrooms, usually at least a hundred. In large cities, they were normally built in a central, convenient location, while in tourist resorts the panoramic situation and outdoor spaces (terraces, gardens, parks, etc.) were an important added value that could contribute to ensuring the leadership of the hotel in the local market. These hotels were equipped to provide the utmost comfort of the time and high quality of service, staffed by numerous, attentive, and discreet personnel.[7]

Therefore, when referring to luxury hotels one is inclined to think of large, fashionable buildings conceived to accommodate upper-class tourists and distinguished guests, such as members of the international jet set, heads of state and government, and to house various kinds of events, including banquets for ceremonies, receptions, and parties, charity galas, business meetings, press conferences, etc.[8]

However, besides performing these primary functions, numerous luxury hotels have also been the scene of historical events, such as diplomatic meetings and peace treaties, as well as intrigues and machinations, thus playing a role in the geopolitical scenario.[9] A growing body of academic literature has highlighted the importance of hotels and hospitality in international relations and diplomacy broadly understood, providing useful interpretative keys to analyze the phenomenon. Specifically, luxury hotels may be the official venue for international negotiations, conferences, or diplomatic encounters. Sometimes this derives from a deliberate choice: the hotel has been selected to host the event because of its location, accommodation capacity (in its broadest sense), or because it represents a neutral ground, ideal for putting at ease every representative of the parties involved in negotiations. Even when the official venue of diplomatic negotiations is not a hotel, luxury hotels in the area usually come into play, performing related functions. First, they accommodate delegations from the guest countries, providing room and board and facilities for the work of the representatives and their subordinate staff, space for informal meetings and backroom deals, as well as opportunities for entertainment and relaxation, etc. Moreover, some of them may be chosen to host formal receptions, such as dinners, working lunches, and gala events, which are an integral part of diplomatic activity.[10]

In providing spaces and atmospheres more or less welcoming, hotels can have an impact on the attitude toward finding a resolution to the dispute, thus contributing to the success or failure of negotiations. Consequently, in the broader context of international relations, luxury hotels can be considered spaces of geopolitical and diplomatic relevance.[11]

The case of the 1922 Genoa Conference, examined in the following paragraphs, not only allows us to deepen little-known aspects of that event, but also enriches existing academic literature on the connections between the hospitality industry and international relations.

Accommodating foreign delegations

In early 1922, the meeting of the Supreme Council of the major Allied powers held in Cannes (6-13 January) conceived the idea of an International Conference with the ambitious goal of promoting the economic reconstruction of Europe after the conflict. Genoa was identified as the venue and the Italian government was therefore tasked with organizational aspects. In this regard, one of the thorny issues to be addressed was finding suitable space to house delegations from the guest countries.[12] At that time, Genoa was an industrial and port city of about 320,000 inhabitants, and not a tourist destination, although it had numerous hotels of various categories.[13] Nevertheless, several coastal resorts had developed within a few kilometers of Genoa. In the years before World War I, significant investments had been made by Italian and foreign hoteliers in these towns. As a result, these resorts succeeded in establishing themselves on the international market as favorite destinations for high-ranking tourists. Thanks to these premises, they were able to overcome the wartime conjuncture and could therefore represent a valuable complement to the Genoese hotel equipment.[14]

The accommodation of foreign delegations posed several problems not only in terms of quantity and quality of hotel facilities. It was necessary to ensure high levels of comfort, as well as privacy, security, and public order. Moreover, the 1922 Conference would attract the attention of many international observers and the foreign press; thus, the eyes of the international public opinion would be upon Italy, and specifically upon Genoa. Therefore, this event could have been an important showcase to convey the image of the country to the world; however, in case of problems it could have turned into a boomerang. The Italian government was well aware of these issues and worked to find the best viable solutions. From an operational point of view, many activities were delegated to the prefect of Genoa, who, as a representative of the government, was charged with handling several practical aspects.[15]

The first problem concerned the choice of facilities in which to house the delegations. Some wealthy Genoese had made available free of charge to the government their villas in the neighborhood of Genoa. These villas could be suitable locations to host the heads of major delegations, such as the Belgian, French, English, and Italian ones. It was necessary, however, to have a large nubmer of hotel rooms to accommodate all the participants and their staff of collaborators.[16] While in the case of mega-events, such as major international expositions (for example World Exhibitions) or major sporting events (such as the Olympic Games), there is a long phase of preparatory work, which imply the reconfiguration of urban spaces, including the construction of new lodging facilities, usually this does not happen for international diplomatic meetings. For these events, it is a widespread practice – at the time, as well as in more recent times – to rely on the existing facilities.[17]

Based on the reports prepared by the prefect of Genoa, it soon emerged that within the city the accommodation capacity of luxury and first-class hotels would not be sufficient for the purpose. It was then crucial to expand the geographical area in which the delegations would be hosted and include some internationally renowned tourist destinations to the west and east of the city. Thanks to special rail connections and car services, the delegations housed in the outlying areas would be able to reach Genoa easily, thus reducing logistical criticalities.

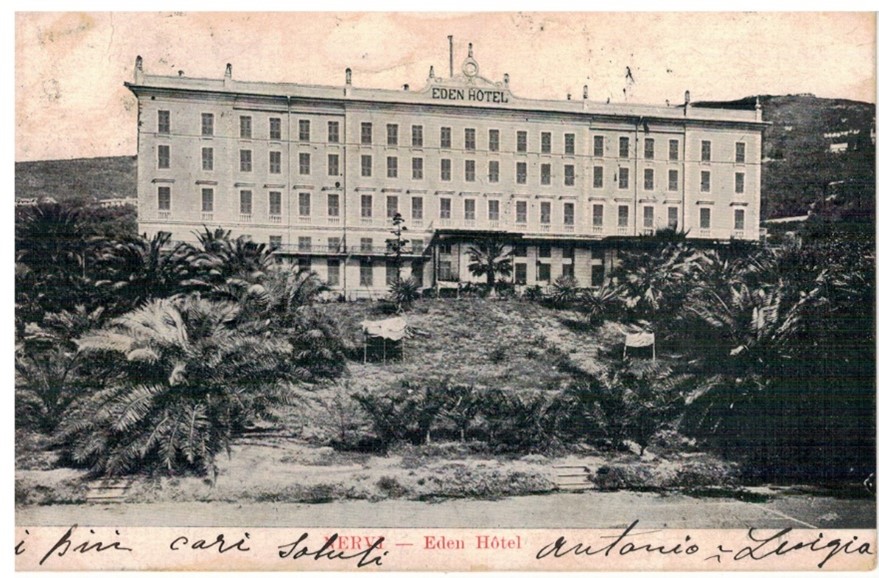

A suitable place was the neighboring seaside resort of Pegli, twenty-minute west of Genoa. However, the town had no luxury hotels; there was only a first-class hotel, the Grand Hotel de la Méditerranée, beautifully situated on the seafront, with one hundred rooms.[18] After careful assessments and meticulous inspections, no other place on the west coast was chosen; the Italian government preferred the coastal resorts along the eastern Riviera. Closest to Genoa was Nervi, which had a couple of suitable hotels: the Grand Hotel Eden and the Hotel Savoia.[19] As it was necessary to find a greater number of rooms, other places along the east coast were chosen, gradually moving away from Genoa up to Santa Margherita and Rapallo, which, on the whole, offered no less than five suitable hotels with hundreds of bedrooms, although distant about forty minutes by train from Genoa.[20]

In the meantime, the Italian government decided that the official sessions of the Conference would be held in the Palazzo San Giorgio, an ancient and prestigious public palace situated in the historic center of the city and overlooking the sea. Regarding many national and foreign press correspondents who had come to Genoa to cover the Conference and report on its official and unofficial events, after evaluating several alternatives, including the use of passenger ships anchored in the port, an ad hoc solution was found. It was decided to host all of them in the center of the city, in two large adjoining buildings that were temporarily equipped as hotels. On the whole, 180 rooms were provided. To facilitate journalists’ work, other dedicated facilities were set up, such as a “house of the press” with press rooms, offices, telephone, telegraph lines, etc. As the hotel and the house of the press were not close to each other, a special bus service was also established to transport journalists from the former to the latter and vice versa.[21]

The second problem was how to allocate delegations to the hotels. Some of them were numerically large and would therefore occupy an entire large-sized hotel or two smaller ones. Other countries, on the contrary, would be sending a handful of people; therefore, a medium-large hotel could accommodate two or more delegations. The choice of how to match delegations housed under the same roof was also vital. It was not just a matter of accommodation capacity: it was crucially vital to avoid potential tensions in light of the diplomatic and geopolitical scenario of the time that might thwart the success of the Conference.[22]

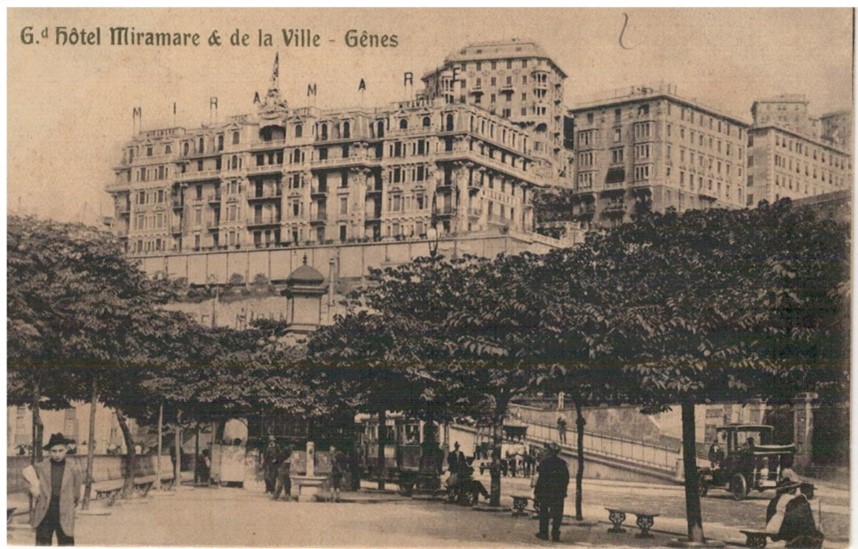

Image 1. Genoa’s Grand Hotel Miramare et de la Ville. It hosted the British, Belgian, and Swiss delegations

Source: Postcard from the author’s collection.

Taking into account all these issues, the Italian government decided how to house foreign guests. Specifically, the delegations from Western European countries and Japan were quartered in Genoa. The luxury and panoramic Grand Hotel Miramare et de la Ville welcomed the English and Belgian delegates; they were joined by the Swiss ones at the express request of the owners of the hotel itself, who were Swiss. The neighboring first-class Grand Hotel Savoia Majestic housed the French delegation. Both these hotels were close to the main railway station and the harbor station. All other delegates lodged in a hotel in the middle area of the city. The Italians stayed at the Grand Hotel Bristol and the Hotel Splendid; the Germans were distributed between the Eden Parc Hotel and the Hotel Bavaria, while the Grand Hotel de Gênes and the Grand Hotel Isotta accommodated the Japanese. Apart from some subordinate staff of the German and Italian delegations, who had to settle for second-class hotels (the hotels Splendid and Bavaria), all the others were welcomed in luxury and first-class hotels.[23]

The delegations of neutral countries, namely Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Holland, and Luxemburg, were housed in Pegli’s Grand Hotel de la Méditerranée. Other groups, from Eastern Europe and the Iberian countries, were scattered in various hotels along the eastern Riviera, from Nervi to Rapallo. The luxury Grand Hotel Eden of Nervi, with its beautiful park, hosted the Polish and Hungarian delegations, together with the Spanish and Portuguese ones, while the first-class Hotel Savoia lodged representatives of Albania, Austria, and Bulgaria. The Yugoslavians were accommodated at the Grand Hotel Guglielmina in Santa Margherita. The Russian delegates, who were under strict observation due to the fears of possible attacks and pro- or anti-Russian demonstrations, were confined in the prestigious, but isolated, Imperial Palace Hotel in Rapallo. Rapallo also welcomed delegations from East-European countries: Latvia, Estonia, Czechoslovakia, Finland, Lithuania, Greece, and Romania distributed among three different hotels.[24]

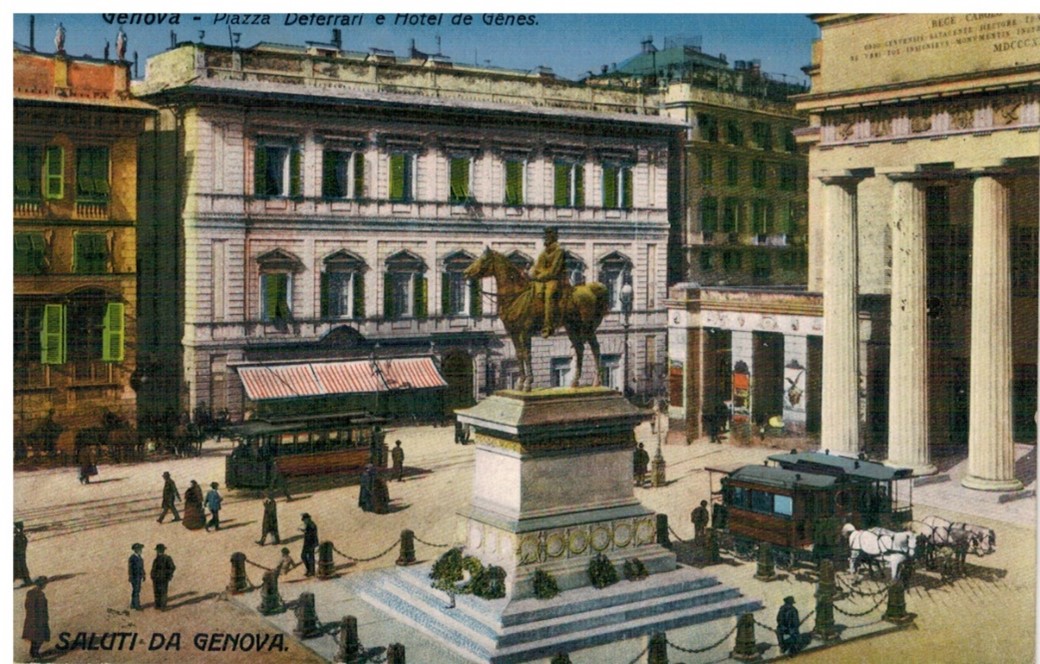

Image 2. Genoa’s Grand Hotel de Gênes in central De Ferrari square. It hosted part of the Japanese delegation and was also a support base in Genoa for the Russian delegation

Source: Postcard from the author’s collection.

In many respects, the distribution of delegations in various places reflects geopolitical reasons as well as the political and economic weight of the country in light of the new order emerging after World War I. These factors were intertwined with practical aspects when deciding how to assign a delegation to a specific hotel, including the choice between luxury, first-class, or even second-class ones. Taking into account the different categories of hotels, special rates were agreed upon for providing room and board to members of a delegation, while additional services were to be contracted directly on a case-by-case basis.[25]

In addition, the hotels and their directors were asked to meet the needs of foreign delegations to the best of their ability and to provide a welcoming atmosphere in every respect. In other words, they were asked to show the world the style and the warmth of Italian hospitality and welcome. For example, menus were revised and included special dishes to be served at luncheons and receptions, such as Caviar du Volga, Choux-fleurs à la Polonaise, Asperges Sauce Hollandaise, Filets de sole à la Colbert, Charlotte à la Russe, Parfait Moscovite.[26]

Table 1. Major foreign delegations and their accommodations, by country

|

Country |

Place |

Hotel |

Category |

|

Albania |

Nervi |

Hotel Savoia |

First class |

|

Austria |

Nervi |

Hotel Savoia |

First class |

|

Belgium |

Genoa |

Grand Hotel Miramare et de la Ville |

Luxury |

|

British Empire |

Genoa |

Grand Hotel Miramare et de la Ville |

Luxury |

|

Bulgaria |

Nervi |

Hotel Savoia |

First class |

|

Czechoslovakia |

Rapallo |

New Kursaal Hotel |

Luxury |

|

Denmark |

Pegli |

Grand Hotel de la Méditerranée |

First class |

|

Estonia |

Rapallo |

Grand Hotel Verdi |

First class |

|

Finland |

Rapallo |

New Kursaal Hotel |

Luxury |

|

France |

Genoa |

Grand Hotel Savoia Majestic |

First class |

|

Germany (1st group) |

Genoa |

Eden Park Hotel |

First class |

|

Germany (2nd group) |

Genoa |

Hotel Bavaria |

Second class |

|

Greece |

Rapallo |

Bristol Hotel |

First class |

|

Holland |

Pegli |

Grand Hotel de la Méditerranée |

First class |

|

Hungary |

Nervi |

Grand Hotel Eden |

Luxury |

|

Italy (1st group) |

Genoa |

Grand Hotel Bristol |

First class |

|

Italy (2nd group) |

Genoa |

Hotel Splendid |

Second class |

|

Japan (1st group) |

Genoa |

Grand Hotel Isotta |

First class |

|

Japan (2nd group) |

Genoa |

Grand Hotel de Gênes |

First class |

|

Latvia |

Rapallo |

Grand Hotel Verdi |

First class |

|

Lithuania |

Rapallo |

New Kursaal Hotel |

Luxury |

|

Luxembourg |

Pegli |

Grand Hotel de la Méditerranée |

First class |

|

Norway |

Pegli |

Grand Hotel de la Méditerranée |

First class |

|

Poland |

Nervi |

Grand Hotel Eden |

Luxury |

|

Portugal |

Nervi |

Grand Hotel Eden |

Luxury |

|

Romania |

Rapallo |

Bristol Hotel |

First class |

|

Russia |

Rapallo |

Imperial Palace Hotel |

Luxury |

|

Spain |

Nervi |

Grand Hotel Eden |

Luxury |

|

Sweeden |

Pegli |

Grand Hotel de la Méditerranée |

First class |

|

Switzerland |

Genoa |

Grand Hotel Miramare et de la Ville |

Luxury |

|

Yugoslavia |

Santa Margherita |

Hotel Guglielmina |

First class |

Source: author’s elaboration based on ASG, PGG, 268.

Several hotels in Genoa, including the Grand Hotel Miramare et de la Ville, the Grand Hotel Savoia Majestic, the Grand Hotel Bristol, and the Grand Hotel de Gênes also hosted some banquets and meetings related to the Conference. Other receptions were held inside various public palaces, such as Palazzo Ducale and Palazzo Reale, and, on April 22, King Victor Emmanuel the Third offered lunch to foreign delegates aboard the battleship “Dante Alighieri” of the Royal Navy.[27]

Although practical problems, especially logistical ones, were not lacking, Genoa and Italy were able to offer cordial hospitality and elicited words of admiration and gratitude from many quarters for the exquisite welcome they received.[28] However, even if no official event was scheduled outside the city of Genoa, it was the Imperial Palace of Rapallo – hosting the Russian delegation – that played a prominent role during the Genoa Conference.

Image 3. Nervi’s Grand Hotel Eden. It hosted the Polish and Hungarian delegations, as well as the Spanish and Portuguese ones

Source: Postcard from the author’s collection.

The role of the Imperial Place Hotel

The Imperial Palace Hotel (today Imperiale Palace Hotel) is a luxury hotel built on a hill located within a vast park with luxuriant vegetation that stretched on the border between the municipalities of Rapallo and Santa Margherita, along the eastern Riviera.[29] It is situated in a particularly valuable panoramic position, allowing a charming view of the coast from Portofino to Sestri Levante. The original nucleus of the hotel consists of a private liberty-style villa built around 1889-90. At the beginning of the 20th century, the initial body of the building was refitted and gradually enlarged to be converted into a new, luxury hotel: the Imperial Palace. It had 180 bedrooms and was equipped with every comfort of the time: elevator, electric lights, central heating, suites with private bathrooms, etc. Since its opening in 1903, the hotel quickly won the favor of the distinguished international clientele, particularly the British and Americans, as well as prominent people in politics, art, and culture. In nearly two decades of activity, it also hosted the Italian royal family and numerous other members of European royalty and aristocracy, including even some exiles who belonged to the Russian nobility.[30] From the point of view of the Italian authorities, the decision to relegate the Russian delegation to the Imperial Palace Hotel was functional to avoid public order problems, ensure adequate protection for the Moscow government’s representatives, and keep them under close surveillance. However, a few days before the delegation’s arrival, rumors had spread that the Russians had formally requested to be accommodated in a hotel in Genoa because they did not consider themselves sufficiently safe in Rapallo. Such rumors, however, had been neither officially confirmed nor denied.[31] The Italian government prepared impressive security measures and deployed a large number of police and intelligence agents inside and outside the building to monitor the situation constantly. Every day a detailed report was prepared concerning the movements of the delegation members and the entries of other people into the hotel, which was passed on to the prefect of Genoa and the government.[32]

The Imperial Palace Hotel undoubtedly constituted an ideal accommodation from the point of view of the Russian delegation as well. It was a prestigious facility, thus showing that the government in Moscow, while being under strict observation, was treated on a par with the great European powers. Since the hotel had more rooms than were needed to accommodate the Russian delegates, the last floor was thus left available to some hotel’s regular guests.[33]

The isolated position of the hotel allowed for sought-after privacy but also implied numerous round-trip travels to Genoa, even several times a day. To reduce such travels, the Russians also rented a hall at the Grand Hotel de Gênes, in the city’s main square. This strategy allowed them to have a support base not far from the Conference venue to implement their diplomatic and communication activity, especially meeting correspondents of the foreign press. The presence of Russian delegates and their movements between Genoa and Rapallo fueled anecdotes and indiscretions that reflected the spasmodic curiosity of the Western international audience, thus allowing them to make headlines.[34]

However, it was precisely in the privacy and elegance of the Imperial Palace Hotel that the well-known Rapallo Treaty was secretly signed between German Foreign Minister Walther von Rathenau and Russian Foreign Commissioner Georgy Vasilyevich Chicherin. This happened on a Sunday, 16 April, the day of the Easter feast, when the Conference’s work was suspended and no receptions, banquets, or other official events were scheduled. The purpose of the agreement was the resumption of diplomatic and economic relations between the two states and the final settlement of the aftermath of World War I. It helped to bring closer together two states that, for several reasons, were isolated on the international political scene and would have important repercussions in the geopolitical and diplomatic spheres far beyond the subsequent working sessions of the Genoa Conference.[35]

Image 4. Rapallo’s Imperial Palace Hotel. It hosted the Russian delegation. It was also the venue of the 1922 Rapallo Treaty between Germany and Russia

Source: Postcard from the author’s collection.

Having been, despite itself, the scene of a major international event, the Imperial Palace Hotel has become part of the political history of the 20th century. When, in the following days, the Treaty was made public, the news quickly made the rounds of the world, thus bringing to the fore the names of Rapallo and the Imperial Palace, which gained impressive popularity and media hype.

The “Oval Hall”, where the Treaty was signed, subsequently renamed – not coincidentally – the “Treaty Hall”, still retains its elegant appearance of a hundred years ago, in perpetual memory of what happened within those walls. Its relevance in the history of international relations is also recognized by a commemorative plaque. This important legacy has allowed and still allows the Imperial Palace Hotel to capitalize on this unique feature in promotional and marketing terms.[36]

Concluding remarks

Accommodating foreign delegations during an international event such as the 1922 Genoa International Economic Conference poses several issues in terms of welcoming, security, diplomacy, and geopolitics, which the Italian government tried to address to the best of its ability and available resources. In this regard, hotels played a crucial, peculiar role from many points of view.

Hotels may be considered discreet and motionless spectators of the Conference and its back ground. They hosted distinguished representatives as well as anonymous members of their staff; they were also the scene of official events, such as receptions and diplomatic negotiations, as well as some coup de théâtre, above all the Rapallo Treaty. During the Conference, this allowed hotels to gain visibility and popularity, and enhance their image with the international public. However, some hotels were also symbolic places of this international gathering, becoming pieces within a larger geopolitical mosaic. Therefore, they have rightfully become part of history and thus preserved a cultural value. Many of these hotels are no longer operational and the buildings have been converted into private apartments, such as Genoa’s Grand Hotel Miramare et de la Ville, Grand Hotel de Gênes, Grand Hotel Isotta, or even Nervi’s Grand Hotel Eden. As a result, the memory of the events that took place inside those buildings between April and May 1922 has fallen into oblivion.

In other cases, however, that memory is still alive today. The most striking example is – not by chance – that of the Imperial Palace Hotel. The hotel was immediately in the spotlight as the headquarters of the Russian delegation. However, after the signing of the Rapallo Treaty between Germany and Russia, it gained a place among historical sites having a role in international geopolitics and diplomacy. This is, probably, the most important legacy of the 1922 Genoa International Economic Conference in terms of historical heritage, able to link luxury hotels, geopolitics, and diplomacy. However, these aspects deserve to be widely considered from a historical cultural heritage enhancement perspective that goes beyond the marketing strategies of individual hotels.

References

[1] P. Bernasconi, G.Zanelli, La conferenza di Genova. Cronache e documenti, L. Cappelli Editore 1922; J.S. Mills, The Genoa Conference, Hutchinson & Co 1992; M. Bottaro Palumbo, La conferenza di Genova e il Trattato di Rapallo cin quant’anni dopo, “L’Est. Rivista trimestrale di studi sui paesi dell’Est”, 1972, 8 (3), pp. 127–149; B.M. Vigliero, La Conferenza Internazionale Economica di Genova del 1922, “La Casana”, 1972, 25 (1), pp. 11–21; Convegno italo-sovietico, La Conferenza di Genova e il trattato di Rapallo (1922), Edizioni Italia-URSS 1974; S. White, The Origins of Détente: The Genoa Conference and Soviet-Western Relations, 1921 1922, Cambridge University Press 1985; C. Fink, The Genoa Conference. European Diplomacy, 1921-1922, Syracuse University Press 1993; P. Battifora, La Liguria dei trattati/Liguria of Treaties, De Ferrari 2001, pp. 68–81.

[2] S. White, The Origins of Détente: The Genoa Conference and Soviet-Western Relations, 1921-1922, Cambridge University Press 1985, p. 123; C. Fink, The Genoa Conference. European Diplomacy, 1921-1922, Syracuse University Press 1993, pp. 144–145.

[3] L. Monzali, La politica estera italiana nel primo dopoguerra 1918-1922, “Italia contemporanea”, 2009, 61, nos. 256–257, pp. 379–406.

[4] N. Muzzarelli, Il turismo in Italia tra le due guerre, “Turistica”, 1997, 6 (1), pp. 46–78; D. Strangio, Tourism as a Resource of Economic Development. Legislative Measures, Local Situations, Accommodation Capacity and Tourist Flows in Italy in the ‘Inter-War Years’, in: Global Tourism and Regional Competitiveness, ed. A. Celant, Patron 2007, pp. 97–130; T. Syrjämaa, Visitez l’Italie. Italian State Tourist Propaganda Abroad 1919-1943. Administrative Structure and Practical Realization, Turun Yliopisto 1997.

[5] A. Zanini, The Emergence of a New Entrepreneurial Culture. Luxury Hotels and Elite Tourism in the Italian Riviera (1860-1914), in: Turismo 4.0. Storia, digitalizzazione, territorio, eds. G. Grego rini, R. Semeraro, Vita e Pensiero 2021, pp. 29–30.

[6] J.M. Lesur, Les hôtel de Paris: de l’au berge au palace, XIXe-XXe siècles, Alphil 2005, pp. 140–144.

[7] E. Denby, Grand Hotels. Reality and Illusion. An Architectural and Social History, Reaktion Books 1998; L. Tissot, L’hôtellerie de luxe à Genève (1830 2000). De ses espaces à ses espaces à ses usages, “Entreprises et Histoire”, 2007, 46 (1), pp. 17–37. DOI: 10.3917/eh.046.0017; C. Humair, The Hotel Industry and its Importance in the Technical and Econo mic Development of a Region: The Lake Geneva Case (1852-1914), “Journal of Tourism History”, 2011, 3 (3), pp. 238–242. DOI: 10.1080/1755182X.2011.598573; H. Knoch, Grandhotels: Luxusräume und Gesellschaftswandel in New York, London und Berlin um 1900, Wallstein 2016; K. James, A.K. Sandoval-Strausz, D. Maudlin, M. Peleggi, C. Humair, M.W. Berger, The Hotel in History: Evolving Perspectives, “Journal of Tourism History”, 2017, 9 (1), pp. 92–111. DOI: 10.1080/1755182X.2017.1343784; D. Bowie, Innovation and 19th Century Hotel Industry Evolution, “Tourism Management”, 2018, 64, pp. 314–323. DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.09.005; C. Larrinaga, La hotelería de lujo en Madrid, 1892-1914, “Pasado Abierto”, 2018, 4 (2), pp. 8–26; D. Bagnaresi, F.M. Barbini, P. Battilani, Organizational Change in the Hospitality Industry: The Change Drivers in a Longitudinal Analysis, “Business History”, 2021, 63 (7), pp. 1175–1196. DOI: 10.1080/00076791.2019.1676230; A. Zanini, The Emergence of a New Entrepreneurial Culture. Luxury Hotels and Elite Tourism in the Italian Riviera (1860-1914), in: Turismo 4.0. Storia, digitalizzazione, territorio, eds. G. Gregorini, R. Semeraro, Vita e Pensiero 2021.

[8] M.W. Berger, Hotel Dreams: Luxury, Technology, and Urban Ambition in America, 1829-1929, Johns Hopkins University Press 2011; A. Tessier, Le Grand Hôtel. L’invention du luxe hôtelier (1862-1972), Presses universitaires de Rennes 2012.

[9] J.K. Walton, Tourism and Politics in Elite Beach Resorts: San Sebastián and Ostend, 1830-1939, in: Construction of a Tourism Industry in the 19th and 20th Century: International Perspectives, ed. L. Tissot, Alphil 2003, pp. 287–301; J.K. Walton, Grand Hotels and Great Events: History, Heritage and Hospitality, in: Beau-Rivage Palace: 150 Years of History, ed. N. Maillard, Infolio 2008, pp. 102–112.

[10] S. Fregonese, A. Ramadan, Hotel Geopolitics: A Research Agenda, “Geopolitics”, 2015, 20 (4), pp. 793–813. DOI: 10.1080/14650045.2015.1062755; S. Baranowski, L.P. Covert, B.M. Gordon, R.I. Jobs, C. Noack, A.T. Rosenbaum, B.C. Scott, Discussion: Tourism and Diplomacy, “Journal of Tourism History”, 2019, 11 (1), pp. 63–90. DOI: 10.1080/1755182X.2019.1584974; A. Langer, The Hotel on the Hill: Hilton Hotel’s Unofficial Embassy in Rome, “Diplomatic History”, 2022, 46 (2), pp. 375–396. DOI: 10.1093/dh/dhab100.

[11] R. Craggs, Hospitality in Geopolitics and the Making of Commonwealth International Relations, “Geoforum”, 2014, 52 (1), pp. 90–100. DOI: 10.1016/j. geoforum.2014.01.001; A.T. Park, Accommodating the Post-War Order: the Hotel Brauner Hirsch and the Diplomacy of the Paris Peace Conference in Teschen Silesia, 1919-1920, “Journal of Tourism History”, 2021, 12 (1), pp. 53–74. DOI: 10.1080/1755182X.2021.1895328.

[12] M. Petricioli, L’Italia alla conferenza di Cannes, in: La Conferenza di Genova e il Trattato di Rapallo (1922), Atti del Convegno italo-sovietico Genova-Rapallo, 8-11 giugno 1972, Edizioni Italia URSS 1974, pp. 394–434; S. Tognetti Buriana, Echi della preparazione della conferenza di Genova al parlamento italiano, in: La Conferenza di Genova e il Trattato di Rapallo (1922), Atti del Convegno italo-sovietico Genova-Rapallo, 8-11 giugno 1972, Edizioni Italia-URSS 1974, pp. 517–547.

[13] G. Felloni, The Population Dynamics and the Development of Genoa, 1750-1939, in: Population and Society in Western European Port-Cities, c. 1650–1939, eds. R. Lawton, R.W. Lee, Liverpool University Press 2002, pp. 74–90; A. Zanini, Imprenditoria e ospitalità alberghiera a Genova tra Otto e Novecento, in: Im prenditorialità e sviluppo economico. Il caso italiano (secc. XIII-XX), eds. F. Amatori, A. Colli, Egea 2009, pp. 1176–1206.

[14] A. Zanini, Un secolo di turismo in Liguria. Dinamiche, percorsi, attori, FrancoAngeli 2012, pp. 17–48.

[15] To reconstruct the aspects presented in this paragraph, a wealth of unpublished sources preserved at the Genoa State Archives were examined. See Archivio di Stato di Genova, Prefettura di Genova, Gabinetto 1879-1945 [hereafter ASG, PGG], box files Nos. 266, 267, and 268.

[16] ASG, PGG, 268.

[17] M. Roche, Mega-Events and Modernity: Olympics and Expos in the Growth of Global Culture, Routledge 2000; D. Strangio, A Question of Definition. Literature and Variable Strategies for Mega Events, “Annali del Dipartimento di Metodi e Modelli per l’Economia, il Territorio e la Finanza”, 2016, 17, pp. 149–166. For specific examples, see: A. Fiadino, The 1960 Olympics and Rome’s Urban Transformations, “Città e Storia”, 2013, 8 (1), pp. 173–214. DOI: 10.17426/38232; D. Strangio, Mega Events and their Importance. Some Frameworks for the City of Rome, “Città e Storia”, 2013, 8 (1), pp. 229–242. DOI: 10.17426/93202; M. Teodori, Exceptional Hospitality for a Mega Event and Permanent Housing. Innovative Solutions for the Universal Exposition of Rome in 1942, “Città e Storia”, 2013, 8 (1), pp. 137–171. DOI: 10.17426/34592; D. Strangio, Les grands événements et le rôle des expositions. Art et Culture de l’Expo 1911 à Rome, “Sociétés”, 2018, 140 (2), pp. 11–21. DOI: 10.3917/soc.140.0011.

[18] A. Zanini, Un secolo di turismo in Liguria. Dinamiche, percorsi, attori, FrancoAngeli 2012, pp. 65–86.

[19] A. Zanini, Nervi: From Health Resort to Cultural Tourism, in: Villa Pagoda Hotel, Tormena 2021, pp. 7–47.

[20] A. Zanini, Un secolo di turismo in Liguria. Dinamiche, percorsi, attori, FrancoAngeli 2012, pp. 29–39.

[21] ASG, PGG, 267 and 268.

[22] During the Conference, representatives of not officially invited countries, such as Armenia, Azerbaijan, or Georgia also arrived in Italy. They found accommodation independently at other hotels in Genoa or the Rapallo area (ASG, PGG, 267).

[23] ASG, PGG, 268.

[24] See Table 1.

[25] ASG, PGG, 268. Hospitality expenses of Belgium, French, and British delegations were borne by the Italian government to reciprocate the welcome received during previous diplomatic meetings, while all the other countries had to bear the costs of food and lodging.

[26] ASG, PGG, 268. See also chronicles in local newspapers, especially: “Il Caffaro”, “Il Corriere Mercantile”, and “Il Secolo XIX”.

[27] For the complete program, including the official and related events, see Cerimonie, ricevimenti e banchetti durante la Conferenza, “Il Comune di Genova. Bollettino municipale”, 1922, 2 (9), pp. 21–22.

[28] B.M. Vigliero, La Conferenza Internazionale Economica di Genova del 1922, “La Casana”, 1972, 25 (1), pp. 11–21. See also articles published in “Il Caffaro”, “Il Corriere Mercantile”, and “Il Secolo XIX” during the period of the Conference and in its aftermath.

[29] At that time, the hotel was situated in the territory of the municipality of Rapallo; however, in 1928, municipal boundaries were re-drawn, and the Imperial Palace came under the municipality of Santa Margherita.

[30] K. Baedeker, Northern Italy, including Leghorn, Florence, Ravenna and Routes through France, Switzerland, and Austria. Handbook for Travellers. Fourteenth remodelled edition, Karl Baedeker 1913, p. 134; L. Gravina, Rapallo e Golfo Tigullio. Guida illustrata, Tipografia Colombo 1921, p. 32; U. Tegani, Perle della Riviera. III. Santa Margherita Ligure, “L’Albergo in Italia”, 1933, 9 (2), pp.68–69; G. Pacciarotti, Grand Hôtel. Luoghi e miti della villeggiatura in Italia, 1890-1940, Nomos 2006, p. 106; C. Olcese Spingardi, Grandi Alberghi e Ville della Belle Époque nel golfo del Tigullio, Sagep 2012, p. 18.

[31] See rumors published in Italian newspapers, such as: “Il Mare”, 1 April 1922; “La Stampa”, 5 April 1922.

[32] S. White, The Origins of Détente: The Genoa Conference and Soviet-Western Relations, 1921-1922, Cambridge University Press 1985, pp. 122–125. For these reports, see ASG, PGG, 266, 267 and 268.

[33] S. White, The Origins of Détente: The Genoa Conference and Soviet-Western Relations, 1921-1922, Cambridge University Press 1985, p. 123.

[34] C. Fink, The Genoa Conference. European Diplomacy, 1921-1922, Syracuse University Press 1993, p. 146; S. White, The Origins of Détente: The Genoa Conference and Soviet-Western Relations, 1921-1922, Cambridge University Press 1985, pp. 124–126.

[35] R. Morgan, The Political Significance of German-Soviet Trade Negotiations, 1922-5, “The Historical Journal”, 1963, 6 (2), pp. 253–271. DOI: 10.1017/ S0018246X00001096; P. Fornaro, Rapporti economici e politici tra Germania e URSS prima della ripresa delle relazioni ufficiali, in: La Conferenza di Genova e il Trattato di Rapallo (1922), Atti del Convegno italo-sovietico Genova-Rapallo, 8-11 giugno 1972, Edizioni Italia-URSS 1974, pp. 162–174; G.N. Goroshkova, Il trattato di Rapallo: la sua legittimità storica e il suo antefatto, in: La Conferenza di Genova e il Trattato di Rapallo (1922), Atti del Convegno italo-sovietico Genova-Rapallo, 8-11 giugno 1972, Edizioni Italia-URSS 1974, pp. 561–567; I. Kulinič, Genova e Rapallo: una nuova tappa nei rapporti fra le Repubbliche Sovietiche e i paesi dell’Europa occidentale, in: La Conferenza di Genova e il Trattato di Rapallo (1922), Atti del Convegno italo-sovietico Genova-Rapallo, 8-11 giugno 1972, Edizioni Italia-URSS 1974, pp. 568–582; R. Himmer, Rathenau, Russia, and Rapallo, “Central European History”, 1976, 9 (2), pp. 146–183. DOI: 10.1017/ S000893890001815X; S. White, The Origins of Détente: The Genoa Conference and Soviet-Western Relations, 1921-1922, Cambridge University Press 1985, pp. 157–161; P. Krüger, A Rainy Day, April 16, 1922: The Rapallo Treaty and the Cloudy Perspective for Germany Foreign Policy, in: Genoa, Rapallo, and European Reconstruction in 1922, eds. C. Fink, A. Frohn, J. Heideking, Cambridge University Press 1991, pp. 49–64; P. Battifora, La Liguria dei trattati/Liguria of Treaties, De Ferrari 2001, pp. 87–103.

[36] History of the Imperiale Palace Hotel, https://www.imperialepalacehotel.it/en/luxury-hotel-portofino-bay/history, (access 05.09.2022).