Guriy Borodkin, Walter E. Block

Full Article: View PDF

How to cite

Borodkin G., Block W.E., The Minimum Wage Law: A Snare and a Delusion, “Polish Journal of Political Science”, 2023, Vol. 9, Issue 2, pp. 47–64, DOI: 10.58183/pjps.06022023.

ABSTRACT

In the view of many people, understandably, and all too many economists, disgracefully, the minimum wage law actually boosts compensation for people who would otherwise earn less than the amount established by this legislation. This is a snare and a delusion. In actual point of fact, this law increases the wages of no one at all, at least not in equilibrium; rather it leads to unemployment for those workers unfortunate to have a marginal revenue product below the level mandated by this enactment. It is the burden of the present paper to make good on this claim.

Keywords: Minimum wage, unemployment, productivity

Introduction

The minimum wage has been at the forefront of policy for decades now. People debate endlessly on whether it should be increased, and if so by how much, and on its various employment effects.

This essay hopes to address that, though before we delve deeper into the argument, we must first define what a minimum wage is. This law sets a price floor on wages in a certain industry or a geographical area. The first federal minimum wage was instituted in 1938, with the Fair Labor Standards Act, though they had existed locally prior to that.[1]

Then the price of something increases, people will demand less of it.[I] Customers will purchase fewer bananas if they are $2 rather than $1 a pound, ceteris paribus; this concept applies to labor as well. Making it illegal to pay less than a certain wage does not render the worker magically more productive, and if they don’t turn a profit for the employer they will stay unemployed. A minimum wage does not make it illegal to refuse to hire or to fire someone after all.

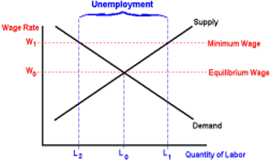

Figure 1. Wage Rates and Quantity of Labor

Source: Own study.

The presented diagram illustrates this process: (see Figure 1).[II] The supply of labor is increasing while the demand curve is decreasing, as we move from left to right. In a free market, the wage rate would be set by the intersection of the two curves at W0 . But assume, somehow, that the wage rate is kept from falling below W1 . Now the new intercept point becomes where the demand curve and W1 meet at L2 . After this minimum is instituted, all labor between L2 and L1 becomes unemployed. Clearly, we can now see the remedy to this unemployment is to let wages fall to the old equilibrium point at L0 W0 . Even from this simple analysis of an employment graph we can see the negative effects of a minimum wage.[III]

Deadweight loss

The minimum wage also creates deadweight loss. The area in diagram 1 between the supply and demand curve and L2 and L0 depicts deadweight loss. This area shows the loss of economic efficiency that occurs when supply and demand are not at equilibrium. The area below the demand curve between L2 and L0 shows the value placed on this labor. The area below the supply curve between these two points on the horizontal axis indicates its cost. The former is larger than the latter by that triangle. And, yet, thanks to this legislation, that number of workers simply cannot be hired.

The minimum wage removes the possibility for a business to hire cheap labor to do menial work. It disallows the physically and mentally disadvantaged to be hired as well, or people who are inexperienced. It attacks the weakest economic actors in society. The deer is a frail animal, but it has a compensating differential: speed. Ditto for the skunk and smell, and the porcupine with its quills. Unskilled workers of all types and varieties, those victimized by racial hostility also have a compensating differential: the ability to work for a lower wage. This evil law removes that option from them. Rather than a lower wage, one compatible with their lower productivity,[2] they must endure unemployment.

Imagine a restaurant has six employees: three cooks, one manager, one waiter, and one janitor. Now suppose the minimum wage is raised, and they’re forced to lay-off the janitor. This not only now means the other restaurant staff have to do more work to compensate, but they will also most likely do a worse job since they weren’t trained for this. Thus, this enactment leads to inefficiency through-out the economy.

Employers will only hire someone if they believe they are profitable, likewise employees will only accept that job if they believe it is personally beneficial, i.e. profitable to the employee. Laws that deprive people of making free choices only do harm to both sides.

Labor-capital substitution

In the view of some commentators,[3] another possible result of a minimum wage hike is labor-capital substitution. As the price of labor rises without an increase in productivity, employers will be forced to make labor inherently more productive. This can only be done through a build-up of capital goods, which makes it possible to produce more or serve more customers at once than before. Consequently, this will also result in a decrease in the amount of labor required to serve the same number of customers, and without that increase in demand and overall wages throughout the economy, there will not be a need to replace those workers, resulting in structural unemployment.

Some people may see this substitution as a good thing, as we are moving towards a more efficient and productive economy, but this criticism falls victim to one of the most omnipresent problems of economics, being unable to see the unseen. You can see the effect this capital-substitution has on productivity and general output, but you cannot see the resources used to create this capital; resources that were moved from other production lines to fill the need for this capital. So while there may be an increase in productivity in the restaurant sector, with self-order kiosks filling the stores, you cannot see the hit the shipping industry took, where resources were moved from producing ships to making those self-order kiosks. The economy would have been better off had the minimum wage not made the economy produce more self-order kiosks.

There is yet another difficulty with this scenario. It is incompatible with the “coulda – woulda” insight. If increasing capital so as to boost labor productivity would have been in the economic interest of employers, they would have already done just that, without any impetus deriving from the minimum wage law. If they “could have” raised profits in this way, they already “would have.”[4]

Pass-through

Here is yet another fallacy, along similar lines. A business obtains its funding from many different sources, and it pays for the maintenance costs of the business with those sources. One of those is the actual product or service the business offers, so often what the firm will do is nudge prices up to compensate for an increase in labor costs, due, in turn, to a boost in the minimum wage level. This is known as cost push, where a business passes the additional labor cost imposed by the minimum wage through to the consumer.

But this claim fails due to the same “coulda – woulda” phenomenon.[5] Before the advent of the minimum wage, or an increase in its level, we assume equilibrium. That is, that prices were optimal, not too high, not too low. We posit that if higher prices led to more profits, they would already have been introduced. We stipulate, specifically, if they were any higher, profits would decrease. Now we introduce the minimum wage or its elevation. The previous considerations still hold. That is, if prices were higher, profits would be lower. Another difficulty with this position is that it assumes, incorrectly, that just because the minimum wage was increased, anyone’s wage would follow suit. This cannot occur, at least not in equilibrium, since wages are predicated upon marginal revenue product and no mere change in the law can alter them.

Another factor in a business not increasing prices after a minimum wage hike is the relative ease with which they could replace, for example, three employees making $5/hr with someone who earns $15/hr. This will not be as efficient as employing the low skilled workers, otherwise the more effective laborer would have already been on the job. But it does further demonstrate which type of person suffers most from this legislation: those at the bottom of the economic pyramid, the very people thought by many to be most helped by it.

Reduction of workplace benefits and amenities

Employers will often reduce workplace amenities and job benefits in response to a minimum wage increase. Employers do this as a way to cut labor costs without reducing wages.

Currently, benefits such as healthcare and pension account for about 30% of an employee’s pay, but following a minimum wage increase, employers may be able to take from that pool to cover for a higher wage cost. This is another potential reason why some studies have not found a decrease in employment after a minimum wage hike, as employers are just taking from costs that were originally in benefits and using that to cover the enlarged wage cost. This may not only come in the form of benefits either, things like workplace comfort may also be sacrificed in order to keep employees and the firm profitable. For example, before a minimum wage or its increase, the air conditioner was always running to keep the store and employees cool in the summer, but after this occurred the temperature would have been raised.

One might push back on this by saying that it’s good that the employer is shifting funds from benefits to the employees’ actual wage, because now the employees can more freely spend their money instead of enjoying better working conditions. But this falls flat in two regards. For one, the employee initially agreed to those benefits for a reason, they obviously must have thought they were worth the loss in salary. Secondly, if not, then they would have not accepted the job, or would have asked for a reduction in benefits and more take home pay.

Internship

What is an internship? This refers to a program in which an unskilled laborer, typically a youngster, works under the mentorship of a skilled practitioner, and learns the techniques necessary to become a more productive employee. And there is one other characteristic of this arrangement. No wages are paid. Or, to put matters in an alternative manner, the salary is zero.

One might think that such an arrangement might be illegal, given a regime of the minimum wage law. After all, a non-existent wage, no matter how you slice it, is less than any minimum wage ever set, including the very first one, at $ 25 per hour. How is it then the internships are not seen as criminal?

This is exceedingly difficult to answer. One possibility is that an internship is more of a teaching relationship than actual work. However, the latter also constitutes a learning relationship, as in the well-known phenomenon of on-the-job training. It is entirely plausible that the internship weighs teaching more than working, and jobs in the market incline in the opposite direction. But the opposite may also well occur: some jobs stress learning more than actual production, and some internships do the very opposite. No, this can hardly be an explanation of the exception, nor a justification.

This can only be speculative, but it might well be that internships are not declared illegal per se since the powers that be wish to make it so. It is sometimes said that if the economic interventionists, such as those responsible for the minimum wage in the first place, did not have a double standard, they would have no standards at all.[6]

Monopsony

Let us consider one last argument in behalf of this legislation, which denies its unemployment effects, at least within a given range.7 If there is monopsony in operation in the economy, then, within a certain range, not only will not the minimum wage law fail to engender unemployment, it will actually lead to more employment. There are two arguments against this claim. First, the very concept of monopsony is intellectually incoherent, as it is predicated upon interpersonal comparisons of utility, which are themselves invalid.[8]

Second, it simply does not and cannot apply to unskilled labor of the sort that earns wages at or near the minimum wage level. A monopsony is the only firm that can hire a certain type of labor.

Let us be generous here and include oligopsony, several companies that fit this bill. For example, if you are a professional basketball player in the U.S. there are only 17 teams that can hire you. If you are a narrowly specialized engineer, physicist, chemist, there may be only a few, or perhaps even one company that can effectively employ your skills. But labor of this sort commands hundreds of dollars per hour. No minimum wage law was ever even contemplated pegged at such levels. Now, consider floor sweepers, or office cleaners, or maids, or people who ask if you “want fries with that.” These, in sharp contrast, are the types of employees whose earnings are within a mile of minimum wage laws. But they can work for hundreds of thousands of organizations, if not literally millions. Monopsony, oligopsony, simply cannot apply to them. So this argument in support of the minimum wage simply cannot be relevant.

Conclusion

We have offered several arguments critical of the minimum wage. Chiefly amongst them is that this law creates unemployment for those least able to afford it. In attacking those at the bottom of the economic pyramid, this enactment is particularly noxious.

Explanatory footnotes

[I] The only supposed exception to this claim is the Giffen good, where the income effect outweighs the substitution effect. For the claim that this is not merely empirically unlikely, but actually illogical and thus praxeologically invalid, see: I. Wysocki, W.E. Block, The Giffen good – a praxeological approach, “Wroclaw Economic Review”, 2018, Vol. 24, No. 2, 9–22, DOI: 10.19195/2084-4093.24.2.1; G. Philbois, W.E. Block, The Z Curve: Supply and Demand for Giffen Goods, “MISES Journal”, 2018, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 1–8; W.E. Block, I. Wysocki, A defense of Rothbard on the demand curve against Hudik’s critique, “Acta Economica Et Turistica”, 2018, Vol. 4, No.1, pp. 47–61; W.E. Block, W. Barnett II, Giffen Goods, Backward Bending Supply Curves, Price Controls and Praxeology; or, Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Boogie Man of Giffen Goods and Backward Bending Supply Curves? Not Us, “Revista Procesos de Mercado”, 2012, Vol. IX, No. 1, pp. 353–373; W.E. Block, Thymology, praxeology, demand curves, Giffen goods and diminishing marginal utility, “Studia Humana”, 2012, Vol. 1 (2), pp. 3–11; W. Barnett II, W.E. Block, The Antimathematicality of Demand Curves, “DialoguE E-Journal”, 2010, Vol. 1, pp. 23–31; R.P. Murphy, R. Wutscher, W.E. Block, Mathematics in Economics: An Austrian Methodological Critique, “Philosophical Investigations”, 2010, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 44–66; P.G. Klein, A note on Giffen goods, Revised 5 November 2009, http://sites.baylor.edu/peter_klein/files/2016/06/giffen-t82d17.pdf, (access 12.09.2023); P.G. Klein, J.T. Salerno, Giffen’s Paradox and the Law of Demand, https://mises.org/library/giffen%E2%80%99s-paradox-and-law-demand, (access 12.09.2023).

[II] We are extremely humiliated and embarrassed to place such a diagram in an article published by a refereed peer-reviewed journal such as this one. If the world were as it should be, such diagrams would be confined to textbooks appropriate for freshman economics courses. But we are forced to do so because there is an entire subset of economic literature dedicated to the denial of the correctness of the lessons taught by this very simple, but not simplistic, diagram. See in this regard: R.D. Atkinson, The Pro-Growth Minimum Wage, “Democracy: A Journal of Ideas”, 2018, No. 49, available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3324645, (access 12.09.2023); A. Dube, T.W. Lester, M. Reich, Minimum wage effects across state borders: estimates using contiguous counties, “The Review of Economics and Statistics”, 2010, Vol. 92, No. 4, pp. 945–964; F. Gavrel, I. Lebon, T. Rebière, Wages, selectivity, and vacancies: Evaluating the short-term and long-term impact of the minimum wage on unemployment, “Journal of Economic Modelling”, 2010, Vol. 27, Issue 5, pp. 1274–1281; R. Dickens, S. Machin, A. Manning, The Effects of Minimum Wages on Employment: Theory and Evidence from Britain, “Journal of Labor Economics”, 1999, Vol. 17, Issue 1, pp. 1–22; N. Williams, J.A. Mills, Minimum wage effects by gender, “Journal of Labor Research”, 1998, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 397–414; D. Card, A. Krueger, A Reanalysis of the Effect of the New Jersey Minimum Wage Increase on the Fast-Food Industry with Representative Payroll Data, Working Paper 6386, NBER 1998; W. Wessels, Restaurants as monopsonies: Minimum wages and tipped services, “Economic Inquiry”, 1997, Vol. 35, pp. 334–349; D. Webster, Wage analysis computations, in: The State of Working America 1996-97, eds. M.J. Bernstein, J. Schmitt, M.E. Sharpe 1997, pp. 423–430; J. Bernstein, J. Schmitt, The Sky Hasn’t Fallen: An Evaluation of the Minimum-Wage Increase, “Journal of Labor and Society”, 1997, Vol. 1, Issue 3, pp. 81–91; M. Zavodny, The minimum wage: maximum controversy over a minimal effect, Ph.D. dissertation, Submitted to the Department of Economics in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1996; D. Acemoglu, Good Jobs versus Bad Jobs: Theory and Some Evidence, Working Paper Department of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1996; K.A. Swinnerton, Minimum wages in an equilibrium search model with diminishing returns to labor in production, “Journal of Labor Economics”, 1996, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 340–355; R.E. Prasch, In Defense of the Minimum Wage, “Journal of Economic Issues”, 1996, Vol. 30, Issue 2, pp. 391–397; R. Freeman, The minimum wage as a redistributive tool, “The Economic Journal”, 1996, Vol. 106, No. 436, pp. 639–649; D. Card, A. Krueger, Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage – Twentieth-Anniversary Edition, Princeton University Press 1995; A. Manning, Labour markets with company wage policies, Discussion Paper No. 214, Center for Economic Performance, London School of Economics 1994; S. Machin, A. Manning, The effects of minimum wages on wage dispersion and employment: Evidence from the U.K. wage councils, “Industrial and Labor Relations Review”, 1994, Vol. 47, No. 2, pp. 319–329; W. Spriggs, B.W. Klein, Raising the Floor: The Effects of the Minimum Wage on Low-wage Workers, Economic Policy Institute 1994; D. Card, A. Krueger, Minimum wages and employment: A case study of the fast-food industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, “American Economics Review”, 1994, Vol. 84, No. 4, pp. 487–496; D. Card, Do minimum wages reduce employment? A case study of California, 1987-89, “Industrial and Labor Relations Review”, 1992, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 38–54; D. Card, Using regional variation in wages to measure the effects of the federal minimum wage, “Industrial and Labor Relations Review”, 1992, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 22–37; A. Wellington, Effects of the minimum wage on the employment status of youths: An update, “Journal of Human Resources”, 1991, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 27–46; K. Burdett, D.T. Mortensen, Equilibrium Wage Differentials and Employer Size, Discussion Paper No. 860, Center for Mathematical Studies in Economics and Management Science 1989; C. Brown, C. Gilroy, A. Kohen, The Effect of The Minimum Wage on Employment and Unemployment, “Journal of Economic Literature”, 1982, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 487–528; P. Krugman, Raise that wage, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/18/opinion/krugman-raise-that-wage.html?_r=0, (access 12.09.2023). Are we too harsh in characterizing the authors herein mentioned, many of them prestigious economists, as traitors to the dismal science? We think not. They disavow very, very, very basic economic analysis. This would be the equivalent of mathematicians rejecting the Pythagorean theorem, or, for that matter, that 2+2=4. For the claim that rejecting the notion that this legislation creates unemployment, not increased wages is not only an empirical matter, but also matter of pure logic (praxeology) see: W.E. Block, The Minimum Wage Necessarily Increases Unemployment for the Unskilled, “Journal of Innovations”, 2023, forthcoming.

[III] The “contribution” of most of these professional economists who support the minimum wage law consists of econometric analyses which fail to show any of its unemployment effects. The proper response to this is twofold. One, try harder; those effects are there; perhaps they take longer to register than your analysis allows. Two, we are assuming ceteris paribus conditions, and econometric analysis is but an imperfect attempt to ensure this. For more sensible economists who point to the unemployment effects of this enactment see: J. Lingenfelter, J. Dominguez, L. Garcia, et al., Closing the Gap: Why Minimum Wage Laws Disproportionately Harm African-Americans, “Economics, Management, and Financial Markets”, 2017, 12 (1), pp. 11–24; R. Batemarco, C. Seltzer, W.E. Block, The Irony of the Minimum Wage Law: Limiting Choices Versus Expanding Choices, “Journal of Peace, Prosperity & Freedom”, 2014, Vol. 3, pp. 69–83; C. Hovenga, D. Naik, W.E. Block, The Detrimental Side Effects of Minimum Wage Laws, “Business and Society Review”, 2013, Vol. 118, Issue 4, pp. 463–487; P. Cappelli, W.E. Block, Debate over the minimum wage law, “Economics, Management, and Financial Markets”, 2012, 7 (4), pp. 11–33; H. Hazlitt, Economics in One Lesson, Ludwig von Mises Institute 2008; D.B. Klein, S. Dompe, Reasons for Supporting the Minimum Wage: Asking Signatories of the ‘Raise the Minimum Wage’ Statement, “Econ Journal Watch”, 2007, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 125–167; W.E. Block, The Minimum Wage: A Reply to Card and Krueger, “Journal of The Tennessee Economics Association”, 2001, https://www.walterblock.com/wp-content/uploads/publications/block_minimum-wage-once-again_2001.pdf, (access 12.09.2023); P. McCormick, W.E. Block, The Minimum Wage: Does it Really Help Workers, “Southern Connecticut State University Business Journal”, 2000, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 77–80; D. Neumark, W. Wascher, Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania: Comment, “American Economic Review”, 2000, Vol. 90, No. 5, pp. 1362–1396; R.V. Burkhauser, K.A. Couch, D. Wittenburg, “Who Gets What” from Minimum Wage Hikes: A Re-Estimation of Card and Krueger’s Distributional Analysis in Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage, “Industrial and Labor Relations Review”, 1996, Vol. 49, No. 3, pp. 547–552; D. Neumark, W. Wascher, Minimum wage effects on employment and school enrollment, “Journal of Business Economics and Statistics”, 1995, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 199–206; D. Neumark, W. Wascher, The Effect of New Jersey’s Minimum Wage Increase on Fast-Food Employment: A Re-Evaluation Using Payroll Records, Working Paper 5224, NBER 1995, D. Deere, K. Murphy, F. Welch, Employment and the 1990-91 Minimum-Wage Hike, “American Economic Review”, 1995, Vol. 85, No. 2, pp. 232–237; L. Gallaway, A. Douglas, Review of Card and Krueger’s Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage, “Cato Journal”, 1995, Vol. 15, No.1, pp. 137–140; D. Hamermesh, F. Welch, Review Symposium: Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage, “Industrial and Labor Relations Review”, 1995, Vol. 48, Issue 4, pp. 827–849; D. Neumark, W. Wascher, Employment Effects of Minimum and Subminimum Wages: Panel Data on State Minimum Wage Laws, “Industrial and Labor Relations Review”, 1992, Vol. 46, No.1, pp. 55–81; T. Rustici, A public choice view of the minimum wage, “Cato Journal”, 1985, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 103–131; W.E. Williams, The State Against Blacks, New Press 1982; J. Mincer, Unemployment effects of minimum wages, “Journal of Political Economy”, 1976, Vol. 84, No. 4, pp. 87–104; M. Friedman, A minimum-wage law is, in reality, a law that makes it illegal for an employer to hire a person with limited skills, http://izquotes.com/quote/306121, (access 12.09.2023); G.S. Becker, It’s Simple: Hike The Minimum Wage, And You Put People Out Of Work, http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/stories/1995-03-05/its-simple-hike-the-minimum-wage-and-you-put-people-out-of-work, (access 12.09.2023); G. Leef, My Case against Minimum-Wage Laws, https://mises.org/wire/my-case-against-minimum-wage-laws, (access 12.09.2023); V. Vuk, Professor Stiglitz and the Minimum Wage, http://mises.org/daily/2266, (access 12.09.2023); D. Neumark, The Effects of Minimum Wages on Employment, FRBSF, https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2015/december/effects-of-minimum-wage-on-employment/, (access 12.09.2023); G. North, How Minimum Wage Laws Promote Racial Discrimination, https://www.lewrockwell.com/2014/07/gary-north/want-young-black-males-to-get-jobs/, (access 12.09.2023); G. Reisman, How Minimum Wage Laws Increase Poverty, https://mises.org/library/how-minimum-wage-laws-increase-poverty, (access 12.09.2023); S.H. Hanke, Minimum Wage Laws Kill Jobs, https://www.cato.org/blog/minimum-wage-laws-kill-jobs, (access 12.09.2023); S.H. Hanke, Let the Data Speak: The Truth Behind Minimum Wage Laws, https://www.cato.org/commentary/let-data-speak-truth-behind-minimum-wage-laws, (access 12.09.2023); B. Powell, Krugman Contra Krugman on the Minimum Wage?, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/krugman-minimum-wage_b_4428174, (access 12.09.2023); G. Galles, Cognitive Dissonance on Minimum Wages and Maximum Rents, https://mises.org/library/cognitive-dissonance-minimum-wages-and-maximum-rents, (access 12.09.2023); B. Gitis, How Minimum Wage Increased Unemployment and Reduced Job Creation in 2013, https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/how-minimum-wage-increased-unemployment-and-reduced-job-creation-in-2013/, (access 12.09.2023); M.N. Rothbard, Against the Minimum Wage, https://www.lewrockwell.com/1970/01/murray-n-rothbard/outlawing-jobs-the-minimum-wage-oncemore/, (access 12.09.2023).

References

[1] The Fair Labor Standards Act Of 1938, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/WHD/legacy/files/FairLaborStandAct.pdf, (access 12.09.2023).

[2] If they could but get a job in the first place, their productivity might well increase, due to on-the-job training. If so, their wages would increase, to keep pace with this new found increase in marginal revenue product of theirs. But they are excluded from this opportunity by that law. Too many people falsely think of the minimum wage as a floor under wages; raise it, and compensation rises. No. A better metaphor is a hurdle over which an applicant must jump in order to be employed in the first place. Raise the level mandated by this law, and it becomes harder and harder to “jump” over it into employment.

[3] D. Aaronson, S. Agarwal, E. French, The Spending and Debt Response to Minimum Wages Hikes, The Federal Reserve of Chicago 2009.

[4] Here we are of course assuming, arguedo, equilibrium before and after the introduction of the minimum wage law, and ceteris paribus conditions.

[5] For a critique of cost push inflation, see: T.M. Humphrey, Historical Origins of the Cost-Push Fallacy, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, “Economic Quarterly”, 1998, Vol. 84/3, pp. 53–74; D.S. Batten, Inflation: The Cost-Push Myth, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 1981, Vol. 63, pp. 20–26; H. Hazlitt, Cost Push Inflation?, http://mises.org/daily/4829, (access 12.09.2023); R. Blumen, The Financial Apocalyptics Are Back, http://mises.org/daily/2637, (access 12.09.2023); F. Shostak, Will An Oil Price Fall Push Inflation Down?, https://mises.org/library/will-oil-price-fall-push-inflation-down, (access 12.09.2023).

[6] We owe this way of putting the matter to Rabbi Dov Fischer.

[7] This argument is very important in that it undermines one of the best reductios ad absurdum against this law: if it is so good, why stop at $5 or $10 or $12 or $15 or even $25 per hour? Why not boost it to, oh, $1 million per hour? If this law really boosts salaries, then we would all be rich. Why not end all foreign aid to poor countries, and, instead, just advise them to institute a minimum wage law at that level? Then they, too, would all become wealthy.

[8] It would take us too far afield from our present concerns to make this case even roughly. Instead, we content ourselves with mentioning the literature that makes this case: W.E. Block, W. Barnett, Monopsony Theory, “American Review of Political Economy”, 2009, Vol. 7 (1/2), pp. 67–109; D. Bellante, The Non Sequitur in the Revival of Monopsony Theory, “The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics”, 2007, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 15–24; M.N. Rothbard, Man, economy, and state with Power and market: government and economy, Ludwig von Mises Institute 2004; D. Costea, A Critique of Mises’s Theory of Monopoly Prices, “The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics”, 2003, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 47–62; A. Tabarrok, Separation of Commercial and Investment Banking: The Morgans vs. The Rockefellers, “Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics”, 1998, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 1–18; T.J. DiLorenzo, The Myth of Natural Monopoly, “Review of Austrian Economics”, 1996, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 43–58; F. McChesney, Antitrust and Regulation: Chicago’s Contradictory Views, “Cato Journal”, 1991, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 775–798; W.H. Hutt, Trade Unions: The Private Use of Coercive Power, “The Review of Austrian Economics”, 1989, Vol. III, pp. 109–120; M. Reynolds, An Economic Analysis of the Norris LaGuardia Act, the Wagner Act and the Labor Representation Industry, “The Journal of Libertarian Studies”, 1982, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 227–266.