Sylwia Badaczewska

Full Article: View PDF

How to cite

Badaczewska S., Police Actions during Securing Mass Events on the Example of Football Matches Held in Warsaw, “Polish Journal of Political Science”, 2024, Vol. 10, Issue 1, pp. 38–64, DOI: 10.58183/pjps.04012024.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this article is to characterize the security measures employed by the Police at mass events, using football matches held in Warsaw as an example. These measures consist of a variety of activities that, when properly prepared and executed, contribute to ensuring safety during such events. The main tasks of the Police involve conducting preventive and operational-reconnaissance activities. In the event of a threat to public safety and order, responding to disclosed prohibited acts becomes a crucial issue. This publication also includes survey results and information obtained from expert interviews.

Keywords: police, mass event, public safety and order, operational and reconnaissance activities, prohibited actions

Introduction

The aim of this article is to analyze both the methods and conditions under which the police ensure safety and public order during mass events, such as football matches, in the capital city of Warsaw. Mass events are a topic extensively discussed in literature dedicated to security issues. These events are organized on a large scale, ranging from various performances to the football matches discussed in this article.

The capital city of Warsaw, being the capital of Poland, hosts a large number of residents of different nationalities, which brings a certain uniqueness to many areas of the city’s activities. As the capital, Warsaw boasts excellent public transport infrastructure, facilitating communication among residents of various nationalities. The city’s public transport system is not only highly developed but also foreigner-friendly, offering information in multiple languages and support for travelers. Additionally, Warsaw provides many other amenities for foreigners, such as advisory services for expatriates, information centers, and diverse cultural meeting places that foster integration and cultural exchange. As a result, the capital of Poland becomes a welcoming and accessible place not only for its residents but also for people from different parts of the world attending mass events like football matches.

In Poland, the legislation regulating all matters related to the organization and conduct of mass events is the Act on the Safety of Mass Events of 20 March 2009.[1] This act encompasses the most important aspects of these events, particularly covering the principles and methods of organizing mass events, as well as the duties of the organizer and specific services ensuring safety. According to this normative act, a mass event should be understood as an artistic-entertainment event, as well as a mass sports event, including football matches.[2]

In connection with the organization of mass events in Warsaw, it is necessary for services to be prepared for various types of threats, including those related to participants not complying with legal regulations. The specificity of mass events in the capital city of Warsaw is particularly tied to the large number of participants these events attract. This is due to the presence of central state authorities and the National Stadium, where around one hundred events are held annually, some of which are challenging to secure. Preparation and organization pose a logistical challenge, particularly when ensuring the safety of tens of thousands of spectators at a football match or an artistic event (e.g., a concert). An important aspect is adapting to the continuous changes occurring in society, which may translate into acts of aggression at mass events.[3] It is crucial to develop effective crowd management strategies and respond quickly to various incidents that occur during mass events. Continuous improvement of safety procedures and training of personnel responsible for event management are essential to maintaining high safety standards in the city.

Among the many research methods used to develop this article were document analysis, surveys, observation methods, and an expert interview with a former police officer who wished to remain anonymous. The survey was conducted from April 28 to May 5, 2022, using the Google Forms platform. The study involved 32 respondents who were working individuals (5 women and 27 men), aged between 20 and 50 years, with secondary or higher education. The survey aimed to obtain information regarding mass events (specifically football matches) and the security provided by the police. Ultimately, it served as an element of the author’s thesis titled “The Role of the Police in Securing Mass Events on the Example of the Capital City of Warsaw.”

In the context of the analyzed normative acts, the most significant proved to be the Act on the Police of 6 April 19904 and the aforementioned Act on the Safety of Mass Events of 20 March 2009. Among the literature, the most significant turned out to be the book titled “Managing the Safety of Mass Events and Public Gatherings” by Mariusz Nepelski and Jarosław Struniawski, as well as the publication by Witold Apolinarski titled “The Specificity of the Actions of Police Riot Units,” included in the Scientific Journals of the Main School of Fire Service.

Public safety threats related to mass events using football matches as an example

Events such as mass gatherings are accompanied by a significant risk of various threats that can affect the safety of participants. These threats include risks to the health and even the lives of people in the vicinity of the match, such as fights or the possibility of a terrorist attack. According to the Polish language dictionary, a threat is defined as “a situation or condition that poses a danger to someone or in which someone feels endangered; also: someone who creates such a situation.”[5] According to the National Security Bureau dictionary, a security threat is defined as “direct or indirect destructive actions against a subject.”[6]

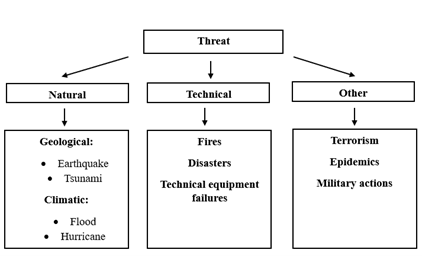

When discussing threats, it’s important to remember that they can be classified in various ways. The criteria for classification depend particularly on their origin, type, and field of activity. It is worth making a brief classification of threats here to facilitate understanding of the topic presented in the article. According to Krzysztof Ficoń, classification can relate to spatial scope, level of destruction, and elimination time.[7] Another type of classification could be based on Romuald Grocki’s approach. This author characterizes threats by their primary sources that contribute to their emergence. His classification primarily relies on causal criteria.[8] According to this classification, threats can be categorized into natural, technical, social, and other types.[9] This classification, modified by Artur Pisarek, is represented in the diagram below.

Figure 1. Example classification of threats based on their source and manner of occurrence

Source: A. Pisarek, Uwarunkowania zapewnienia bezpieczeństwa…, op. cit., p. 19.

Given the adopted approach, attention should be focused on the threats associated with football matches, which will serve as the primary case study for analyzing safety during mass events. Through the lens of these sporting events, various aspects related to crowd management, security procedures, and law enforcement responses to potential threats will be examined. This analysis will lead to a better understanding of the challenges and effective strategies in ensuring safety at large public gatherings.

One of the many threats during football matches is stadium hooliganism. The associated dangers include risks to health and human life, as well as property damage and financial losses due to the disruption of the event.[10] Football hooliganism is a specific and unfortunately still quite common phenomenon. In Poland, it is recognized as a deviant behavior, referring to the pathology of hooliganism itself.[11] It occurs very often and is usually associated with the presence of pseudo-supporters, commonly known as hooligans, at matches. Pseudo-supporters are individuals linked to sports fan communities but engage in criminal and aggressive activities. They often provoke deviant behaviors such as fights and organized brawls known as ustawki, which are pre-planned altercations outside the stadium by groups of fans. These actions lead to significant social and economic problems, including financial losses, the need for a large police presence, and concerns among residents about their safety.[12] In Poland, stadium excesses began in the mid-1970s, coinciding with the emergence of organized fan movements. This period marked the beginnings of organized fan clubs in Poland. Small groups of supporters wearing club colors and cheering for their teams during matches, both at home and away, started to appear. Over time, friendships between fans of different clubs began to form, known as zgody. Each major group of fans also identified their main opponents, known as kosy.[13]

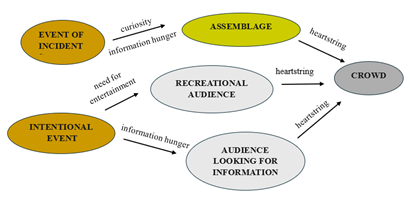

A serious threat during mass events is the danger associated with crowd movement and potential difficulties and incidents in this regard, such as panic, problems navigating obstacles, and the possibility of stampedes. A crowd is defined as “a gathering of many people in a space allowing direct contact, temporarily bound by strong psychological ties, manifested in their common spontaneous behavior.”[14] Directing the crowd during a mass event poses a significant challenge for law enforcement and information services. There are several types of crowds to distinguish. A conventional crowd consists of people gathered in a specific place for a defined purpose. An expressive crowd is characterized by intense emotions. Additionally, there is an active crowd, primarily focused on destructive actions.[15] The diagram below illustrates the process associated with the formation of a crowd, which often accompanies events such as mass gatherings.

Figure 2. Diagram of the crowd formation process

Source: M. Zajdel, Komputerowe modelowanie zachowań zbiorowości ludzkich w stanach paniki, Doctoral dissertation, Akademia Górniczo-Hutnicza im. Stanisława Staszica, Katedra Informatyki 2013, p. 19.

In relation to the crowd movement process, communication routes have been established. These routes are created to minimize the risks associated with crowd panic, which can endanger the health and lives of participants. Communication routes are marked with signs and informational boards designed to guide participants to their seating areas. Each communication route is staffed with information service representatives whose role is to assist participants in finding the correct grandstand or other designated areas they wish to reach during mass events.[16] Proper planning and management of communication routes enable quick and safe access to the event area and facilitate evacuation in case of emergencies that threaten safety. Significant threats during mass events, such as football matches, include disorderly conduct, assaults, drug possession, and disturbances in the stands.

In the case of disorderly conduct, which includes non-compliance or failure to comply with police orders by the crowd, the commander has the right to specify a time frame for compliance. When warning actions do not achieve the intended results and participants show no willingness to comply with commands, it constitutes a breach of rights.[17] Before initiating actions, the commander should assess the situation and determine the deployment of forces and resources. “Police unit commanders, when restoring public order, should employ tactical actions appropriate to the situation, including:

– Blockade actions,

– Dispersal actions, including dividing the crowd, flanking, and encircling.”[18]

From a safety perspective, terrorism poses a significant threat to the organization of mass events. There are various definitions of terrorism, and according to the PWN Encyclopedia, terrorism is defined as “variously motivated, often ideologically, planned and organized actions of individuals or groups, undertaken in violation of existing law to compel specific behaviors and concessions from governmental authorities and society, often infringing upon the rights of innocent bystanders. These actions are carried out with absolute ruthlessness, using various means (psychological pressure, physical violence, use of firearms and explosives), under conditions deliberately created to attract attention and intentionally instill fear in society.”[19] Terrorism in the context of mass events is a serious threat that requires special attention and advanced security measures. Personally, I believe that prevention and swift response to potential threats are crucial to ensuring participants’ sense of security. International cooperation, the use of modern technologies, and public education can significantly reduce the risk of terrorist attacks during large gatherings.

Preventive activities, including close sub-units

Police actions related to mass events such as football matches have a particular character due to the frequent occurrence of crisis situations during these events. The behaviors of participants in mass events are unpredictable and pose risks to the police and other security services, as described above. These threats require the services to be adequately prepared, both technically and practically, during command operations.

The execution of actions imposed on the police is carried out through specific departments. These include the prevention, investigative, and criminal departments, as well as those that support the actions of the aforementioned departments.[20] Thanks to the collaboration of Police services at all organizational levels, it is possible to properly carry out the tasks of each department. Typically, the criminal department performs its tasks in an unnoticed and covert manner. On the other hand, the prevention services (prevention department) operate visibly to citizens. This department includes officers who perform their duties as district officers, organizational units for patrol and intervention, traffic police units, police counter-terrorism units, and police riot units – Police Prevention Units (OPP) and Independent Police Prevention Units (SPPP).[21]

It is important to note that these compact subdivisions[22] also include units formed for operations based on members of the police force who are engaged in other duties, including officers from patrol and intervention departments, which are non-permanent units and sections of the police force.[23] It is worth mentioning that officers from specialized units carry out their assigned tasks during interventions, preventive security measures, actions, or police operations. This includes large-scale events where police specialized units are utilized. These events require significant effort and extensive preparation by the authorities to ensure proper security measures.[24]

Serious and collective disturbances of public order are addressed using dispersal actions. These actions are undertaken by specialized units to separate the crowd and compel them to move to locations designated by the authorities.25 If the crowd becomes aggressive and engages in acts of violence, specialized units and sections employ tactics involving the concentrated use of force and resources. This includes:

– Physical force: Officers use physical force such as batons, riot shields, and other equipment to disperse an aggressive crowd;

– Chemical agents: Chemical substances like tear gas or incapacitating agents may be deployed to disperse the crowd and compel withdrawal;

– Technical means: Technical support measures, such as water cannons, are utilized to control the crowd and secure the area.

Specialized units are equipped with, among other things: “protective shields, helmets with visors, ballistic vests, forearm and leg protectors, impact-resistant gloves, gas masks;

- assault batons, handcuffs;

- gas and acoustic grenades;

- reinforcement measures:

— smoothbore firearms;

— backpack-mounted pepper spray launchers;

— water cannons;

- armored personnel carriers.”[26]

When it comes to the use of direct coercion methods by specialized units, a command from the unit’s commander is required. An exception to this rule is situations where immediate action is imperative to prevent harm to human life, health, or property.[27]

When discussing the operations of specialized units, it’s important to characterize their tactical approach. Officers from specialized units carry out their tasks as part of interventions, preventive security measures, actions, or police operations.[28] During football matches, various situations can lead to diverse injuries such as fractures, or sprains. The causes of such incidents during football matches are numerous and primarily depend on the environment where official duties are performed. One of the most dangerous threats is the behavior of perpetrators aimed at causing serious harm and injury to officers from specialized units. Perpetrators use objects that can cause serious damage in their attacks. Such situations often occur at football matches where pseudo-fans commit acts that jeopardize the security services.[29] The state of threat or disturbance of public order is addressed using dispersal actions. Specialized units undertake these actions to disperse the crowd and compel them to move to locations designated by the authorities. If the crowd becomes aggressive and engages in acts of violence, specialized units employ tactics involving the concentrated use of force and resources.

Operational reconnaissance activities

The legal basis for operational reconnaissance activities is Article 14 of the Police Act. According to this article, within the scope of its tasks, the Police perform operational reconnaissance, investigative, and administrative-enforcement activities for the purpose of:

1) “recognizing, preventing, and detecting crimes, fiscal offenses, and misdemeanors;

2) searching for persons evading law enforcement or the justice system, hereinafter referred to as ‘wanted persons’;

3) searching for persons who, due to an event preventing determination of their whereabouts, need to be located to ensure protection of their life, health, or freedom, hereinafter referred to as ‘missing persons.’”[30]

Furthermore, the Police, while performing tasks defined by law and conducting operational reconnaissance activities, have the right to use personal data, including those in electronic form, and data obtained from other services.[31] During the execution of these activities, officers may also observe and record events in public places using technical tools for visual and audio monitoring.[32]

Operational reconnaissance activities in the context of mass events such as football matches focus on securing participants and maintaining public order. These activities involve covertly identifying groups of pseudo-fans to gather information about their actions. This information can include whether they are organizing for a particular match, their intentions, and their operational plans. Additionally, the Police seek information regarding possible ustawki, which are planned attacks on fans of the opposing team.

The process of gathering information is supported by covert observation, cooperation with confidential sources, criminal analysis, and sometimes operational controls.[33] Covert observation (including ad hoc actions) may involve police officers blending into the crowd of spectators in the stands, concealing their actual tasks and identities, and transmitting relevant information. This information is typically relayed via radio or telephone to the operations center, where it is analyzed and used as a basis for decision-making regarding security management at the mass event. This is part of broader efforts aimed at ensuring the safety of all participants and protecting infrastructure and public property.

It is important to note that these activities may also continue after the conclusion of the mass event. One such activity involves monitoring conversations related to illegal behavior among pseudo-fans. Plainclothes police officers are also assigned duties in areas adjacent to the mass event, primarily in parking lots, stadiums, and significant gathering spots near the event site.

Police response to criminal offenses

Responding to situations that constitute criminal offenses and pose a threat to safety and public order is one of the main tasks of the Police during the security of mass events.[34] “All actions taken during such situations are complex and challenging, as the police may face accusations of either restricting civil liberties or failing to fulfil their duties.”[35] The response to a specific criminal act largely depends on the level of threat. The best solution in such situations is the prompt arrival of a uniformed police officer. The response should be swift and decisive for initial incidents. “Offenders are removed promptly, while the rest of the crowd is generally calmed down.”[36]

When dealing with aggressive crowd disturbances during sporting events, the police employ police lines, which are formations created by police units. If the crowd becomes aggressive and engages in acts of violence, police units and specialized teams use tactics involving the mass deployment of force and resources. In such situations, the police aim to break the resistance, detain the most aggressive participants, and completely disperse the crowd.[37] It is also possible to use service horses and dogs, whose presence alone acts preventively and effectively discourages individuals from disturbing public order.[38] During football matches, the throwing of flares onto the pitch is a common issue. In such cases, if law enforcement is unable to control the situation, police officers establish a cordon in front of the affected sector.[39] The police also face challenges with individuals bringing and using drugs at mass events, thereby violating the law. In such cases, officers take appropriate actions, including arresting offenders, conducting searches, and securing evidence of the crime as necessary. Additionally, at mass events, there are often intoxicated individuals who disrupt public order. In these situations, such individuals are cautioned, and if necessary, escorted out of the stands by the police if warnings prove ineffective.[40] “Sometimes, there are incidents of physical assault on participants at mass events, which require a quick response to prevent escalation into a brawl or further violence. Unfortunately, these incidents are particularly common at football matches, where tensions can escalate between rival groups of fans.”[41] Responding to this type of crime is challenging, as identifying the actual perpetrators is often hindered by the resulting chaos and the tendency of individuals to cover their faces. In some cases, these efforts require gathering evidence, such as reviewing stadium surveillance footage. It is also important to address safety issues around the stadium and public transportation, where law violations frequently occur. Intelligence patrols are present in these areas as well, as crimes such as thefts, especially on buses and trams when fans are traveling to or from matches, are common.[42]

Examples of securing mass events held in the capital city Warsaw

Mass events held in the capital city of Warsaw have a distinct specificity. As previously mentioned, this is largely due to its status as the capital of Poland. It serves as a prime location for hosting large-scale events, often attended by international visitors. Occasionally, an ordinary mass event can escalate into a situation that significantly threatens the health and safety of its participants. Nearly 800 mass events are organized in Warsaw annually, which entails significant responsibility and a substantial amount of work for the various cooperating agencies.

Hundreds of mass events have taken place in Warsaw. This subsection focuses on the analysis of sports events due to their potentially high risk to public safety and the complexity of law enforcement interventions. Examining these cases allows for a thorough understanding of the crisis management strategies employed and an assessment of their effectiveness in protecting citizen safety and upholding the law.

One such event was the recent match to determine the winner of the Polish Cup, with the victor earning the right to compete in the qualifying rounds of the 2022/2023 UEFA Europa Conference League. This event took place on May 2, 2022. In the final of the Fortuna Polish Cup, Raków Częstochowa defeated Lech Poznań 3-1.[43] During these matches, a total of 18 people were detained. More than half were charged with disrupting the match. The remaining individuals were involved in other offenses, such as drug possession, hooliganism, insulting police officers, and assaulting them. There were also two particularly dangerous incidents during the event. The first occurred before the end of the first half when a group of hooligans attempted to storm the stadium, but the police successfully thwarted this breach using direct coercive measures. The second incident happened after the match ended when a large group of people attempted to “confront the police.” This situation compelled the officers to fire a warning shot into the air using smoothbore weapons.[44]

Another example of a mass event was the “Derby” related to the Ekstraklasa Cup matches between Polonia Warsaw and Legia Warsaw. These matches took place on September 2, 2008, at the stadium on Konwiktorska Street 6 in Warsaw.[45] The security efforts included assistance from the Municipal Guard, which was primarily responsible for patrolling vehicles transporting intoxicated individuals.[46] During this security operation, the officers were attacked with stones and pyrotechnics. The police responded swiftly and decisively, employing direct coercive measures such as physical force and batons. The fans were encircled by a police cordon and then escorted to a location where they could be identified. The surrounded rioters became highly aggressive, lighting flares and throwing them at the officers. Due to the lack of response to calls for lawful behavior, the officers were compelled to use direct coercive measures. As a result of these events, two individuals responsible for assaulting the police were detained. In total, 752 people were arrested during this mass event.

A very significant event was the UEFA European Championship for men, jointly hosted by Poland and Ukraine. Officially known as UEFA Euro 2012, the tournament ran from June 8 to July 1, 2012. After one of the matches, numerous riots broke out on the streets of Warsaw. Clashes occurred between Polish and Russian fans, who used stones, bottles, and even road signs as weapons. Acts of aggression were also directed at the police. After the riots, the area around the National Stadium resembled a battlefield, with destroyed barriers, signs, and other debris scattered everywhere.[47] This was a drastic event that should not have marred such an important sports occasion.

An expert interview provided insights into mass events from the perspective of a police officer who was involved in securing them. “There were hundreds of these events, but each was different in many respects. At high-risk events, the effectiveness of the services is put to the test. Riots often occur, and although hundreds of fans may be apprehended, proving their guilt is very difficult. Prosecutors and courts require detailed and specific information about the actions of each detained individual. Officers working in tight units cannot always identify individual perpetrators, as fans are often dressed similarly and masked. Securing events at the National Stadium presents a significant challenge, particularly with fans arriving by car and all attempting to leave simultaneously after the match. This can involve 2,000 to 3,000 vehicles. Typically, traffic lights in the area are turned off, and the police manually control traffic. The difficulty lies in the fact that this responsibility often falls to just 2 to 4 traffic patrols, who require additional support.”[48]

One of the valuable resources for this article was a survey conducted on the security provided by the police at mass events, primarily football matches, held in the capital city of Warsaw. The results from the individual questions in the survey are presented below.

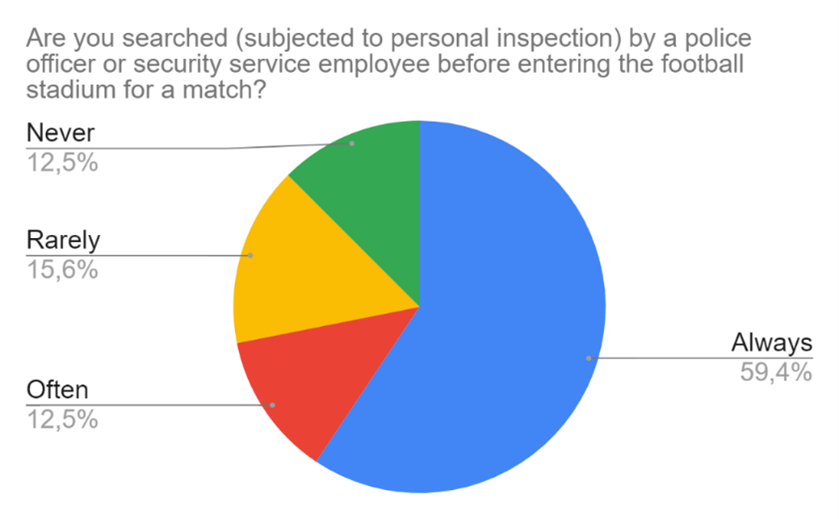

Chart 1. Respondents’ opinions on personal checks during football matches by police officers or security personnel

Source: Materials from the conducted survey – material owned by the author.

The key objective of the survey was to assess the effectiveness of personal searches conducted on participants of mass events. According to the data presented in the chart, over half of the respondents indicated that they are always searched before entering the stadium. Only four individuals reported that they had never been searched. This suggests that personal searches are carried out effectively by both police and security personnel, with minimal objections from the public.[49]

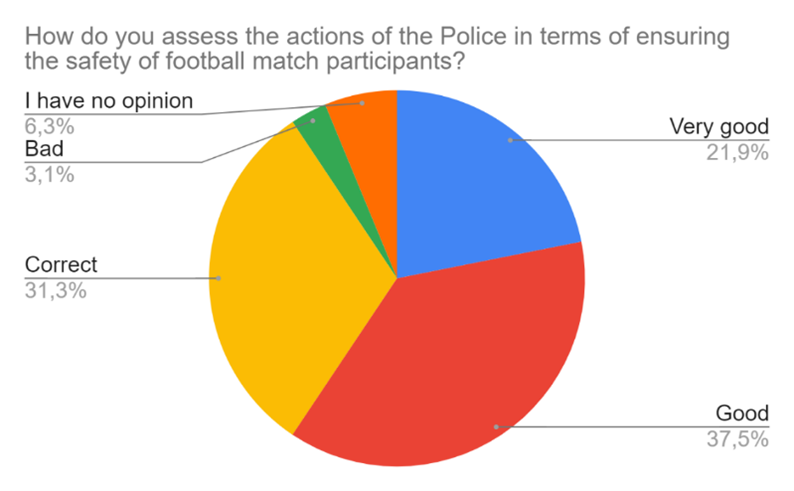

Chart 2. Respondents’ opinions on evaluating the police actions in terms of securing the safety of football match participants

Source: Materials from the conducted survey – material owned by the author.

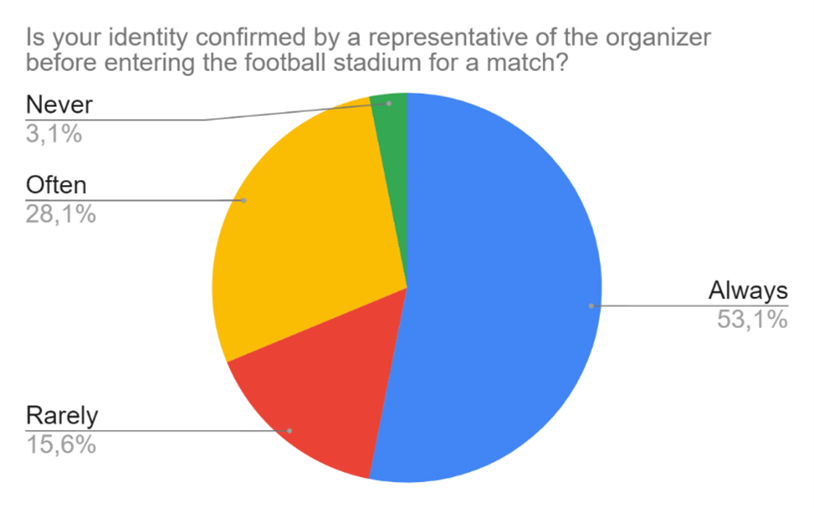

One of the survey questions focused on the confirmation of participants’ identities before entering the stadium. The vast majority of respondents indicated that their identity is always or often confirmed. Only five individuals reported that their identity is rarely confirmed, and just one person stated that their identity has never been verified before entering the stadium. Based on these results, it can be concluded that event safety is generally upheld through diligent checks and confirmation of identities for individuals entering the venue.[50]

Chart 3. Respondents’ opinions on confirming the identity of participants before entering the football stadium

Source: Materials from the conducted survey – material owned by the author.

When evaluating the actions of the police in securing the safety of football match participants, the results of the survey reveal a surprising trend. Despite the common perception that fans generally do not hold a high regard for the police and other security services, the assessment of their actions is relatively positive. The majority of respondents expressed satisfaction with the police efforts to ensure safety. This suggests that, although fans may not have a strong affinity for the police, they generally view their actions positively and feel secure during mass events. This satisfaction is closely linked to the overall sense of security experienced while attending these large gatherings.[51]

Conclusions

Mass events organized in the capital city of Warsaw undoubtedly pose a challenge for both the organizers and the security services. This is due to the unique characteristics of Warsaw as the capital of Poland. Warsaw stands out among other cities in Poland for several reasons. On the one hand, it is an ideal location for hosting mass events due to its central position within the country. On the other hand, the specific elements of its character often lead to significant health risks and even fatalities for participants in these events.

The methodology for securing mass events primarily involves preventive measures aimed at quickly detecting and mitigating any emerging threats. This includes operational and reconnaissance activities focused on gathering information about potential risks and effectively preventing them before they escalate. When threats do arise, it is crucial for the police and other security services to respond promptly. Responses vary depending on the nature of the offense, ranging from verbal warnings to the use of direct coercive measures.

The number of mass events organized in Warsaw is substantial, covering a wide range of types, each significant and often linked to important national events. Based on the analysis of the conducted survey, it can be concluded that the organization of these events generally proceeds without major shortcomings or omissions from the police and security services.

The police actions are divided into specific elements that together create a cohesive and well-planned process. In the event of situations threatening the health or life of participants, officers are required to respond promptly and work to eliminate the danger as quickly as possible. Regarding the resources available to the Warsaw Metropolitan Police Command, they are generally adequate for securing regular mass events. However, challenges arise when dealing with events of higher risk and threat levels. In such cases, these resources may not always be sufficient to handle disruptions efficiently and effectively, necessitating support from additional police units.

To conclude the considerations addressed in this article, it is essential to recognize the critical role of the police in securing mass events. The actions taken by law enforcement are both appropriate and vital, significantly enhancing safety during large gatherings. It is important to highlight that police officers frequently confront substantial dangers, risking their health and lives in the process. Despite these risks, they are dedicated to ensuring that all participants in mass events feel as safe and comfortable as possible.

References

[1] Ustawa z dnia 20 marca 2009 r. o bezpieczeństwie imprez masowych, Dz.U. 2023 poz. 616, [Act of 20 March 2009 on the safety of mass events, Journal of Laws 2023, item 616].

[2] Ibidem, Article 3, paragraph 1.

[3] M. Nepelski, J. Struniawski, Zarządzanie bezpieczeństwem imprez masowych i zgromadzeń publicznych, Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Policyjnej w Szczytnie 2016, p. 19.

[4] Ustawa z dnia 6 kwietnia 1990 r. o Policji, Dz.U. 2024 poz. 145, [Act of 6 April 1990 on the Police, Journal of Laws 2024, item 145].

[5] Dictionary of the Polish language, entry: “zagrożenie” (“threat”), https://sjp.pwn.pl/szukaj/zagro%C5%BCenie.html, (access 11.01.2022).

[6] (MINI) Słownik Biura Bezpieczeństwa Narodowego, [(MINI) National Security Of f ice Dictionary], entry: “zagrożenie bezpieczeństwa” (“security risk”), https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fkoziej.pl%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F09%2FMiniS%25C5%2582ownik-BBN.docx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK, (access 11.01.2022).

[7] K. Ficoń, Inżynieria zarządzania kryzysowego. Podejście systemowe, BEL Studio 2007, p. 78.

[8] A. Pisarek, Uwarunkowania zapewnienia bezpieczeństwa imprez masowych na przykładzie doświadczeń ochrony bezpieczeństwa imprez sportowych w Kielcach, Doctoral dissertation, Uniwersytet Jana Kochanowskiego w Kielcach, Wydział Prawa i Nauk Społecznych 2019, p. 19.

[9] R. Grocki, Zarządzanie kryzysowe. Dobre praktyki, Wydawnictwo Difin 2012, p. 22.

[10] M. Nepelski, J. Struniawski, Zarządzanie bezpieczeństwem imprez…, op. cit., p. 10.

[11] Deviation – a phenomenon strongly deviating from norms in behavior, conduct, or thinking. See: Dictionary of the Polish language, entry: “dewiacja” (“deviation”), https://sjp.pwn.pl/szukaj/dewiacja.html, (access 12.01.2022).

[12] The primary methods and manifestations of hooligan activity generally include set-ups, actions, raids, promotions, and vandalism. The use of hate speech by hooligans, however, often appears to be a secondary or overlooked element, see: P. Piotrowski, Chuligani a kultura futbolu w Polsce, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN 2012, pp. 42–44; P. Chlebowicz, Chuligaństwo stadionowe. Studium kryminologiczne, Oficyna a Wolters Kluwer Business 2009, pp. 154–183.

[13] M. Jurczewski, Prawno-kryminalistyczna problematyka przestępczości stadionowej, Doctoral dissertation, Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, Wydział Prawa 2013, p. 17.

[14] PWN Encyclopaedia, entry: “tłum” (“crowd”), https://encyklopedia.pwn.pl/haslo/tlum;3987627.html, (access 17.01.2022).

[15] A. Pisarek, Uwarunkowania zapewnienia bezpieczeństwa…, op. cit., p. 29.

[16] For regulations on the safety conditions that must be met by stadiums hosting football matches, see: §3, point. 3-5 in Rozporządzenie Ministra Spraw Wewnętrznych i Administracji z dnia 10 czerwca 2010 r. w sprawie warunków bezpieczeństwa, jakie powinny spełniać stadiony, na których mogą odbywać się mecze piłki nożnej, Dz.U. 2010 nr 121 poz. 820, [Regulation of the Minister of Interior and Administration of June 10, 2010 on the safety conditions to be met by stadiums where football matches may be held Journal of Laws of 2010, No. 121, item 820].

[17] M. Nepelski, J. Struniawski, Zarządzanie bezpieczeństwem imprez…, op. cit., p. 204.

[18] Ibidem, p. 205.

[19] PWN Encyclopaedia, entry: “terroryzm” (“terrorism”), https://encyklopedia.pwn.pl/haslo/terroryzm;3986796.html, (access 13.01.2022).

[20] W. Apolinarski, Specyfika działań pododdziałów zwartych Policji, “Zeszyty Naukowe SGSP”, 2017, Vol. 63, No. 3, p. 36.

[21] Ibidem.

[22] Ustawa z dnia 24 maja 2013 r. o środkach przymusu bezpośredniego i broni palnej, Dz.U. 2013 poz. 628, Art. 4, ust. 5. [Act 24 of May 2013 on means of direct coercion and firearms, Journal of Laws 2013, item 628, Article 4, paragraph 5]. A compact subunit is understood to be an organized, uniformly commanded group of officers of the Police, Border Guard, Prison Service or soldiers of the Military Police, carrying out preventive actions in the event of a threat or disturbance to public safety or order.

[23] W. Apolinarski, Specyfika działań pododdziałów…, op. cit., pp. 36–37.

[24] Ibidem, p. 38.

[25] M. Nepelski, J. Struniawski, Zarządzanie bezpieczeństwem imprez…, op. cit., p. 205.

[26] Ustawa z dnia 24 maja 2013 r. o środkach przymusu…, op. cit.

[27] M. Nepelski, J. Struniawski, Zarządzanie bezpieczeństwem imprez…, op. cit., p. 207.

[28] W. Apolinarski, Specyfika działań pododdziałów…, op. cit., p. 38.

[29] Ibidem, p. 40.

[30] Ustawa z dnia 6 kwietnia 1990 r. o Policji…, op. cit., Article 14, paragraph 1.

[31] Ibidem, Article 14, paragraph 4.

[32] Ibidem, Article 15, paragraph 1, point 5a.

[33] Ibidem, Article 19, paragraph 1 and Article 22.

[34] M. Nepelski, J. Struniawski, Zarządzanie bezpieczeństwem imprez…, op. cit., p. 198.

[35] Ibidem.

[36] Statement from an expert interview – in the author’s possession.

[37] M. Nepelski, J. Struniawski, Zarządzanie bezpieczeństwem imprez…, op. cit., p. 206.

[38] Ibidem, p. 207.

[39] Statement from an expert interview – in the author’s possession.

[40] Ibidem.

[41] Ibidem.

[42] Ibidem.

[43] Kto wygrał Puchar Polski? Kto zdobył Puchar Polski?, https://www.polsatsport.pl/wiadomosc/2022-05-02/fortuna-puchar-polski-20212022-kto-wygral-kto-zdobyl-trofeum/, (access 24.05.2022).

[44] P.A. Grubek, Zarzuty dla 18 osób po zamieszkach podczas finału Pucharu Polski, https://www.rdc.pl/public/aktualnosci/zarzuty-dla-18-osob-po-zamieszkach-podczas-finalu-pucharu-polski-posluchaj_wQFkdwgke7fUH5tzE96L, (access 24.05.2022).

[45] M. Nepelski, J. Struniawski, Zarządzanie bezpieczeństwem imprez…, op. cit., p. 217.

[46] Ibidem, p. 218.

[47] Zamieszki podczas marszy Rosjan ulicami Warszawy, 100 zatrzymanych, https://www.rmf24.pl/news-zamieszki-podczas-marszu-rosjan-ulicami-warszawy-100-zatrzym,nId,612146#crp_state=1, (access 24.05.2022).

[48] Statement from an expert interview – in the author’s possession.

[49] Materials from the survey conducted – in the author’s possession.

[50] Ibidem.

[51] Ibidem.